Thursday 29th July, 2021

A NEW MODEL TO TRANSCEND GENERATIONS: THE R107 SL

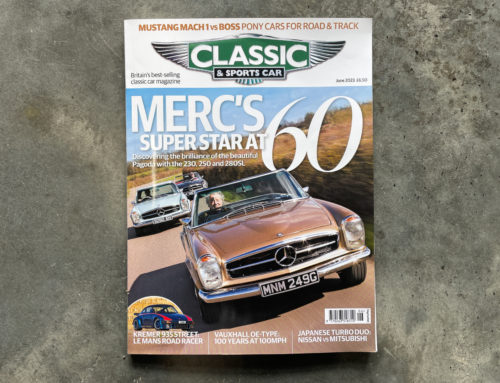

As Mercedes Benz engineers laboured, with their typical thoroughness, on a successor to the W113 ‘Pagoda’ SL in the second half of the ‘60s, not even they could have foreseen that the car they were creating, the R107 SL, would still be with us at the end of the 1900s. Nor that it’d be talked about in the 2021 edition of Classic and Sports Car Magazine.

In all it lasted from 1971 to 1989; if you relate that period of time to popular music we are talking about a vehicle that reigned supreme in its class from the last knockings of Jimi Hendrix to the early days of Kylie Minogue. Or, if you are tuning in from Germany, from Klaus Wunderlich to Bert Kaempfert.

And yet somehow, the older it got the more desirable a property the Peter Pan R107 became. Annual sales peaked at 20,314 units in the car’s 15th year of production, and total output reached 237,287 (of which 156,000 were sold in North America) in an 18-season career only exceeded in the Benz range by the G-Wagen.

The R107 was the product of a time when the very wealthy were fewer in number and had a much narrower choice of true status-symbol motor cars from which to choose. Factoring it its practicality, glamour and open-topped two-seater appeal, it stood almost unchallenged when the build quality of a Mercedes-Benz was not a past-tense fable but a widely understood and entirely justified present-tense reality.

Longer, lower and wider than the car it replaced, the 350SL was the first of the V8-engined SLs, created in the interests of maintaining performance in the face of increasing weight. By the turn of the 1980s, bigger V8s would transform the R107 into a 140mph luxury rocketship, but the original 350SL of 1971 was quick rather than truly fast, with 0-60 in 8 secs and a 128mph maximum.

Its price tag fully lived up to expectations. At £5600 it was nearly twice the cost of a V12 Jaguar E-type and £150 more than a Ferrari Dino, yet on paper it was hardly any faster than the likes of a Datsun 240Z or a Lotus Elan +2S 130. And its 16mpg thirst was almost in the Jensen class.

Daimler-Benz AG had come to the conclusion that this was exactly the sort of sports car its customers wanted: a safe and civilised all-weather luxury two-seater. It was really a grand touring two-door saloon with its hardtop on. Designed around power steering and automatic transmission, and built to the highest standards of fit, finish and durability to be found in a production automobile, it was not so much a sports car as a Teutonic Ford Thunderbird.

The Pagoda had proved buyers’ acceptance of the concept; the R107 updated it with an SL that was now more than equal to the looming crash-safety and environmental challenges of the 1970s. It was also adaptable to the engineering developments in the wider Mercedes-Benz range: no fewer than six sizes of V8 were offered in this body and two flavours of straight-six, these being mainly for buyers who insisted on stirring their own gears – although even the 280/300SLs were mostly ordered as autos.

The model was known internally as the Panzerwagen thanks to its brawny, crash-resistant construction, but it would be wrong to dismiss the R107 series as overweight boulevardiers only suited to 1970s Americans in loud trousers. The spectre of Hart to Hart and Dallas might haunt the R107 to this day, but we should not forget that this car was the last SL to be signed off by Rudoph Uhlenhaut, who certainly knew a good car when he drove one.

Born into the era of DBAG’s dalliance with rotary Wankel power (in the form of its futuristic C111 prototypes), there was nothing radical about this new Mercedes roadster. Its 3499cc M117 engine had first been seen two years earlier in the 280SE 3.5 and 300SEL 3.5 models. Silky and refined, it was a state-of-the-art V8 that revved much faster than its American equivalents and used a then-sophisticated Bosch electronic fuel-injection system controlled by manifold depression, with sensors for crank speed, coolant and air intake temperature.

Theoretically a four-speed manual was standard, but the automatic gearbox was an almost default option. So was the hefty dished hardtop, which was the 350SL’s only real visual link to its elegant predecessor, but it seems that few cars were delivered as hood-only roadsters when the hardtop cost just £215 extra. The ‘Mexican hat’ alloy wheels and heated rear window, in traditional Mercedes-Benz fashion, were chargeable options.

The gently wedge-profiled all-steel body was designed and engineered by the soon-to-retire Karl Wilfert, who had a pedigree at DBAG that went back to 1929. It boasted progressive-crush crumple zones at either end but never had enough rust protection, not even after wax injection and wheelarch liners were introduced in the 1980s. The anti-dive double-wishbone front suspension, with its steering box mounted well aft for safety, had a much less rigorous maintenance regime than the older kingpin type. At the rear, splayed semi-trailing arms – inherited from the 1968 ‘new generation’ saloons – silenced critics of the swing-axle-equipped W113 Pagoda’s behaviour under certain circumstances.

Disc brakes all round were virtually a given on any expensive European car by then, but among the options listed at the 1971 350SL introduction was an ATE anti-lock system. One of the press cars at the SL’s Hockenheim launch was thus equipped but there would be no ABS on production SLs until the mid-1980s.

The 350SL was a short-wheelbase car (in relation to its width) that sat on wide 205/70 tyres and thus had a similar four-square stance to its predecessor. It was the first Benz to have the rectangular headlamps and rubbed, dirt-dodging tail-light lenses that were to be the trademark Mercedes family styling details of the 1970s. There were some concessions to aerodynamics, but most of that was about managing air flow to keep glass and lights clean for safety.

The ‘screen pillars were more steeply raked, and 50% stronger, than the outgoing 280SL, but more obvious was the fact that the clap-hands windscreen wipers were gone and seatbelts were now built into the backs of the seats. A larger fuel tank was placed in a safer position above the rear axle in a car that was 400lb heavier than before but still balanced 50:50 overall.

If the R107 roadsters with their corrugated flanks, will not perhaps be remembered as the prettiest of the SLs, buyers at the time seemed not to care. Even fussy quad headlamps and ‘park bench’ Federal impact bumpers in the American market, where 68% of SLs were sold, could not hurt its image as a genuine object of desire.

Reacting to the first fuel crisis, from 1974 the 280SL came as standard with a manual gearbox (first four, then five speeds from 1980), but neither of the six-cylinder models were much more economical than the V8s. Concurrent with the 3.5-litre car, the 450SL – with anti-squat geometry on its rear suspension – was devised as a way of winning back the performance that had been lost first on US-bound, de-smogged R107s that were badged 350SL 4.5.

In 1973-’80 European form they gave 225bhp, but the only way of differentiating a 280SL from a 450SL (other than the bootlid badge) was the skinnier tyres of the former and the discreet chin spoiler of the latter.

Both sizes of V8 went over to Bosch K-Jetronic injection in the 1975 and came in-unit with a much smoother form of three-speed automatic with a torque convertor. From March 1980, however, the 350 and 450SLs were usurped by new all-alloy V8s of 3.8 and 5 litres to become the 380SL and 500SL, with 218 and 231bhp respectively along with the latest four-speed automatic gearbox. These lightweight V8s were no heavier than the 280SL’s ‘six’, and the gearboxes were lighter than before, too.

In 1981 the R107’s engines benefitted from the ‘energy concept’ enhancements devised for the latest S-Class saloons, with a combination of higher compression ratio and massaged exhaust tracts and combustion chambers improving efficiency, power (240bhp for the 500) and even fuel consumption.

The 380, with a slightly longer stroke, had 10% more torque than the 350SL at 2000rpm and was said to have a faster warm-up time and a reduced idling speed for a 20% improvement in fuel consumption.

Whatever the engine size, these by then decade old two-seaters were all fitted with weight-reducing aluminium bonnets and higher axle ratios. There was an attempt to curb the thirst of the 185bhp M110 engine in the 280SL with an overrun fuel cut-off device. Improved inlet valves and new cam profiles teased further horsepower out of the 500 in 1985 for a lusty 245bhp, with enough torque to give its now standard-fit limited -slip differential a workout. Making it much more of a sports car trait by this point.

At the same time the 380SL became the bored-out 420SL and the 280SL was replaced by the evocatively named 300SL, powered by the latest canted-over 188bhp single-overhead-cam straight-six first seen in the W124 300E.

On all models the front suspension geometry got less offset, lower-profile tyres were introduced (on flat-face alloys) and a chin spoiler was added to reduce front-end lift.

The 560SL was an export-only model, heading to North America, Japan and Australia, restricted to 230bhp by emissions equipment.

Barely 1000 Pagoda SLs came to the UK but the R107s were much more in evidence and are still a fairly regular sight today. Most of the nice ones seem to end up at the SL Shop in Warwickshire which furnished Classic and Sports Car with an early 350SL, a high-spec leather-trimmed 500SL and a straight-six 300SL to get a feel for how the cars developed through the 1970s and ‘80s. ![]()

In Icon Gold, with the full hubcaps, the 350SL is a real period piece to look at, a true slice of ‘70s chic compared to the slightly golf-club smugness of later variants. After the ‘Italian coffee bar’ interior look of the Pagoda, Mercedes-Benz discovered injection mouldings for its plastic dashboards in the ‘70s – colour matching them to the external hue – and offered cloth inserts in addition to the usual MB-Tex or leather for the well-shaped seats. The later SLs have veneers for the centre console, with a token sliver across the dash, but I like the honest austerity of the early car, if not the wrinkly rim of its massive steering wheel. The 300 and 500 have the same design of four-spoke helm but, somehow, the leather cover gives a much more pleasant impression as you guide them through the Warwickshire lanes.

With its headgear in place the 350SL is like a small saloon that just happens to have two seats and superb 360° vision. With their taut, beautifully tailored hoods lowered, windows up and furnace-like heaters blasting away, the 300 and 500 are cosy ways to enjoy the sights, sounds and smells of the countryside in springtime.

The 350SL, from 1974, has quite a gentle feel on the road. It rolls visibly more than the later cars, and has slower and less accurate steering, although weight and feel are good in all three. Its gearbox is there to be used if you want to extract performance; the selector works precisely in the D-S-L gate and the fluid coupling gives a positive feel to the changes compared to the seamless action of the torque-converter-equipped sport/economy transmissions in the 300 and 500. They are higher geared than the 350, in which 80mph equals 4000rpm. In all versions you must engage ‘L’ from rest or push past the resistance at the end of the long accelerator travel to get bottom gear. The 350 and 300 feel equally matched in their strong and lively, rather than startling, straight-line urge. With throttle floored the meaty 500 squats hard on its rear suspension, leaving several yards of burnt rubber in its wake and shoving you up the road with a silky thrust that keeps on coming.

The 350 V8 sounds almost fussy compared to the way the baby 300, with its hydraulic tappets, sings round to 6500rpm. I was left with the feeling that the lusty and lively six-pot R107, with all the late chassis tweaks and refinements, might just be the sweet spot of the range if you are ready to forgo V8 mystique and the period charm of the 1970s SLs.

All versions handle and ride well: substantial without being cumbersome, despite a huge steering wheel that irritated critics for 18 years, and with mild, gently understeering manners that incorporate large margins of safety. An impressive lack of scuttle shake is common to all models, combined with a useful lock that makes them easy cars to manoeuvre.

More than just transport, 50 years on the essential appeal of the R107 remains that of a compact, ‘personal’ and handy possession that manages to combine refinement and creature comforts without feeling in any way decadent, fragile or temperamental. A special car but not an exotic one: a ‘lifestyle’ automobile and timeless default statement of affluence that resonated even with those who had only a passing interest in cars. The luxury roadster everyone’s mum dreamed of – and quite a few dads too.

THE R107’S PLACE IN THE CLASSIC AND SPORTS CAR MARKET

Sam Bailey once had a ‘proper job’ in insurance but quit 13 years ago after meeting fellow Mercedes-Benz enthusiast Bruce Greetham to start the SL Shop. Today, it has 50 employees at its premises near Stratford-upon-Avon. While Bailey guides the brand direction, growing the SL customer base for buying, selling, restoring and selling parts. Greetham, who has a background in the haulage business and fell in love with Mercedes engineering when servicing his guvnor’s W124, has developed the showrooms and workshops where many of the staff are Mercedes-trained, including one veteran mechanic who pre-delivery inspected the R107s when they were new.

“There are not many 1970 SLs left,” says Greetham. “Most have been bodged and been through a lot of hands but, in the future, I think real enthusiasts will buy the early cars. There is a turn in values coming with the 40-year-old-plus, tax-exempt SLs because of the period charm.

“Having said that, the market is still strong for the late cars because they are a little bit more fuel efficient and they give you a little bit more confidence when you drive them. There will always be buyers for good 500s and 300s with the right mileage and the right history. The 300 is a super-crisp and nicely balanced car, which you can push if you really want to.”

Will R107s catch up with the Pagoda values?

“I think if you cherry-pick the right models, yes: 500SLs in the right colours with low miles are already £60-75k cars. But they have to be right.

“We have sold some heavy £80-90,000 R107s in the past 12 months. When we sell those we need to find the person who really appreciates what they are, all the preserved detail.

“We are trying to get drivers back into the right cars after COVID-19, which has changed things a bit because people are deciding if they want an investment car or something to drive and enjoy on the basis that life’s too short. The 45-60,000 miles bracket is a sweet spot here – not so low that you mind putting the miles on it, but still sharp enough to use. Even if you put 10k miles in the next 10 years on an SL like that it will be worth 25% more by then anyway.

“Some parts are getting a bit scarce and Mercedes keeps putting up the prices, which means getting average cars up to a better level is going to be prohibitive for people in the years to come. Some parts are not of the quality they were years ago but, on the other hand, some of the pattern parts can be good.”

HARDTOP’S HARD ACT TO FOLLOW

With 56,330 built from 1972-81 the SLC, the fixed-head coupé sibling of the R107 SL, was a commercial hit in its class. Yet it has always had a slight identity crisis, in that it had neither the wind-in-the-hair appeal of the SL nor the rarefied, hand-finished dignity of the W111 coupés it replaced.

Arguably the most elegant Mercedes-Benz of the 1970s, the SLC was considered to be hugely chic in period (the Americans loved them) and can even claim, in its final homologation-special-5-litre form, to have had a respectable – if brief – rallying career (read Classic & Sports Car, March). Weighing in at 3500lb and on a longer wheelbase, C107s were considered by many to be more forgiving to drive that the short and stubby two-seater SLs.

Launched at the Paris Salon in October 1971 as the 350SLC, this four-seater coupé took its visual lead from the R107 SL rather than the contemporary S-Class saloon. It shared front wings, bonnet and bootlid with the SL but with 14in let in to the R107 chassis to get extra rear-seat legroom. The glazed-in slats in its C-pillars were a visual ruse that allowed the engineers to use a smaller quarter-window that would be able to disappear into the body.

The 350SLC was soon supplemented by the 450SLC. Then, from 1974, tax-avoiding buyers could get the 280 twin-cam straight-six in the coupé. This handsome lump looked nice under the bonnet, and made the 280SLC nearly as fast as the 3.5-litre V8 – but it was nearly as thirsty too.

Most SLCs were automatics but you could order a manual on the 350 and 280 models, not that many customers did. The short-lived 1979-’81 380 and 450 5.0/500SLCs had the revised all-alloy V8s destined for the W126 S-Class. With more than 30,000 built the 225bhp 450SLC was easily the most popular SLC variant. Velour, leather, MB-Tex and tweed cloth were the trim options, but even with a £15,000 price-tag for the 450SLC (which outgunned the V12 XJ-S by £2000) you didn’t get a radio as standard.

MERCEDES-BENZ R107 SL

Sold/number built: 1971-‘89/237,387

Construction: steel monocoque

Engine: iron-block, alloy-head, dohc 2746cc or sohc 2962cc straight-six, sohc-per-bank 3499/4520cc V8, or all-alloy 3818/3839/4196/4973/5547cc V8, all with fuel injection

Max power: 180bhp @ 5700rpm to 245bhp @ 5000rpm

Max torque: 176lb ft @ 4500rpm to 297lb ft @ 3200rpm

Transmission: four/five-speed manual or three/four-speed automatic, RWD

Suspension: independent, at front by double wishbones rear semi-trailing arms; coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar f/r

Steering: power-assisted recirculating ball

Brakes: discs, with servo; optional anti-lock from 1980

Length: 14ft 3.5in (4390mm)

Width: 5ft 8.75in (1790mm)

Height: 4ft 2.5in (1300mm)

Wheelbase: 8ft (2460mm)

Weight: 3307-3781lb (1500-1715kg)

0-60mph: 9.3-7.1 secs

Top speed: 126-140mph Mpg 15.4

Price new: £6995 (350SL, 1973)

Price now: £15-60,000

GRAB YOURSELF A SLICE OF CLASSIC AND SPORTS CAR ROYALTY

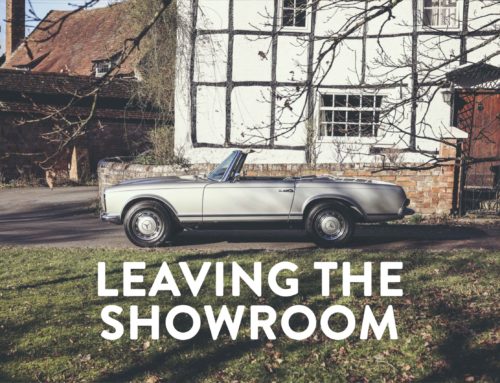

The 1973 350SL discussed by Classic and Sports Car here is available today and ready for a new home. Sitting in the 50,000 mile bracket, this is a car that as Sales Director Bruce Greetham pointed out, will relish another 10,000 miles and still increase by 25% in value.

Available Here.

![]()

Share With Your Fellow Enthusiasts

Thursday 29th July, 2021

A NEW MODEL TO TRANSCEND GENERATIONS: THE R107 SL

As Mercedes Benz engineers laboured, with their typical thoroughness, on a successor to the W113 ‘Pagoda’ SL in the second half of the ‘60s, not even they could have foreseen that the car they were creating, the R107 SL, would still be with us at the end of the 1900s. Nor that it’d be talked about in the 2021 edition of Classic and Sports Car Magazine.

In all it lasted from 1971 to 1989; if you relate that period of time to popular music we are talking about a vehicle that reigned supreme in its class from the last knockings of Jimi Hendrix to the early days of Kylie Minogue. Or, if you are tuning in from Germany, from Klaus Wunderlich to Bert Kaempfert.

And yet somehow, the older it got the more desirable a property the Peter Pan R107 became. Annual sales peaked at 20,314 units in the car’s 15th year of production, and total output reached 237,287 (of which 156,000 were sold in North America) in an 18-season career only exceeded in the Benz range by the G-Wagen.

The R107 was the product of a time when the very wealthy were fewer in number and had a much narrower choice of true status-symbol motor cars from which to choose. Factoring it its practicality, glamour and open-topped two-seater appeal, it stood almost unchallenged when the build quality of a Mercedes-Benz was not a past-tense fable but a widely understood and entirely justified present-tense reality.

Longer, lower and wider than the car it replaced, the 350SL was the first of the V8-engined SLs, created in the interests of maintaining performance in the face of increasing weight. By the turn of the 1980s, bigger V8s would transform the R107 into a 140mph luxury rocketship, but the original 350SL of 1971 was quick rather than truly fast, with 0-60 in 8 secs and a 128mph maximum.

Its price tag fully lived up to expectations. At £5600 it was nearly twice the cost of a V12 Jaguar E-type and £150 more than a Ferrari Dino, yet on paper it was hardly any faster than the likes of a Datsun 240Z or a Lotus Elan +2S 130. And its 16mpg thirst was almost in the Jensen class.

Daimler-Benz AG had come to the conclusion that this was exactly the sort of sports car its customers wanted: a safe and civilised all-weather luxury two-seater. It was really a grand touring two-door saloon with its hardtop on. Designed around power steering and automatic transmission, and built to the highest standards of fit, finish and durability to be found in a production automobile, it was not so much a sports car as a Teutonic Ford Thunderbird.

The Pagoda had proved buyers’ acceptance of the concept; the R107 updated it with an SL that was now more than equal to the looming crash-safety and environmental challenges of the 1970s. It was also adaptable to the engineering developments in the wider Mercedes-Benz range: no fewer than six sizes of V8 were offered in this body and two flavours of straight-six, these being mainly for buyers who insisted on stirring their own gears – although even the 280/300SLs were mostly ordered as autos.

The model was known internally as the Panzerwagen thanks to its brawny, crash-resistant construction, but it would be wrong to dismiss the R107 series as overweight boulevardiers only suited to 1970s Americans in loud trousers. The spectre of Hart to Hart and Dallas might haunt the R107 to this day, but we should not forget that this car was the last SL to be signed off by Rudoph Uhlenhaut, who certainly knew a good car when he drove one.

Born into the era of DBAG’s dalliance with rotary Wankel power (in the form of its futuristic C111 prototypes), there was nothing radical about this new Mercedes roadster. Its 3499cc M117 engine had first been seen two years earlier in the 280SE 3.5 and 300SEL 3.5 models. Silky and refined, it was a state-of-the-art V8 that revved much faster than its American equivalents and used a then-sophisticated Bosch electronic fuel-injection system controlled by manifold depression, with sensors for crank speed, coolant and air intake temperature.

Theoretically a four-speed manual was standard, but the automatic gearbox was an almost default option. So was the hefty dished hardtop, which was the 350SL’s only real visual link to its elegant predecessor, but it seems that few cars were delivered as hood-only roadsters when the hardtop cost just £215 extra. The ‘Mexican hat’ alloy wheels and heated rear window, in traditional Mercedes-Benz fashion, were chargeable options.

The gently wedge-profiled all-steel body was designed and engineered by the soon-to-retire Karl Wilfert, who had a pedigree at DBAG that went back to 1929. It boasted progressive-crush crumple zones at either end but never had enough rust protection, not even after wax injection and wheelarch liners were introduced in the 1980s. The anti-dive double-wishbone front suspension, with its steering box mounted well aft for safety, had a much less rigorous maintenance regime than the older kingpin type. At the rear, splayed semi-trailing arms – inherited from the 1968 ‘new generation’ saloons – silenced critics of the swing-axle-equipped W113 Pagoda’s behaviour under certain circumstances.

Disc brakes all round were virtually a given on any expensive European car by then, but among the options listed at the 1971 350SL introduction was an ATE anti-lock system. One of the press cars at the SL’s Hockenheim launch was thus equipped but there would be no ABS on production SLs until the mid-1980s.

The 350SL was a short-wheelbase car (in relation to its width) that sat on wide 205/70 tyres and thus had a similar four-square stance to its predecessor. It was the first Benz to have the rectangular headlamps and rubbed, dirt-dodging tail-light lenses that were to be the trademark Mercedes family styling details of the 1970s. There were some concessions to aerodynamics, but most of that was about managing air flow to keep glass and lights clean for safety.

The ‘screen pillars were more steeply raked, and 50% stronger, than the outgoing 280SL, but more obvious was the fact that the clap-hands windscreen wipers were gone and seatbelts were now built into the backs of the seats. A larger fuel tank was placed in a safer position above the rear axle in a car that was 400lb heavier than before but still balanced 50:50 overall.

If the R107 roadsters with their corrugated flanks, will not perhaps be remembered as the prettiest of the SLs, buyers at the time seemed not to care. Even fussy quad headlamps and ‘park bench’ Federal impact bumpers in the American market, where 68% of SLs were sold, could not hurt its image as a genuine object of desire.

Reacting to the first fuel crisis, from 1974 the 280SL came as standard with a manual gearbox (first four, then five speeds from 1980), but neither of the six-cylinder models were much more economical than the V8s. Concurrent with the 3.5-litre car, the 450SL – with anti-squat geometry on its rear suspension – was devised as a way of winning back the performance that had been lost first on US-bound, de-smogged R107s that were badged 350SL 4.5.

In 1973-’80 European form they gave 225bhp, but the only way of differentiating a 280SL from a 450SL (other than the bootlid badge) was the skinnier tyres of the former and the discreet chin spoiler of the latter.

Both sizes of V8 went over to Bosch K-Jetronic injection in the 1975 and came in-unit with a much smoother form of three-speed automatic with a torque convertor. From March 1980, however, the 350 and 450SLs were usurped by new all-alloy V8s of 3.8 and 5 litres to become the 380SL and 500SL, with 218 and 231bhp respectively along with the latest four-speed automatic gearbox. These lightweight V8s were no heavier than the 280SL’s ‘six’, and the gearboxes were lighter than before, too.

In 1981 the R107’s engines benefitted from the ‘energy concept’ enhancements devised for the latest S-Class saloons, with a combination of higher compression ratio and massaged exhaust tracts and combustion chambers improving efficiency, power (240bhp for the 500) and even fuel consumption.

The 380, with a slightly longer stroke, had 10% more torque than the 350SL at 2000rpm and was said to have a faster warm-up time and a reduced idling speed for a 20% improvement in fuel consumption.

Whatever the engine size, these by then decade old two-seaters were all fitted with weight-reducing aluminium bonnets and higher axle ratios. There was an attempt to curb the thirst of the 185bhp M110 engine in the 280SL with an overrun fuel cut-off device. Improved inlet valves and new cam profiles teased further horsepower out of the 500 in 1985 for a lusty 245bhp, with enough torque to give its now standard-fit limited -slip differential a workout. Making it much more of a sports car trait by this point.

At the same time the 380SL became the bored-out 420SL and the 280SL was replaced by the evocatively named 300SL, powered by the latest canted-over 188bhp single-overhead-cam straight-six first seen in the W124 300E.

On all models the front suspension geometry got less offset, lower-profile tyres were introduced (on flat-face alloys) and a chin spoiler was added to reduce front-end lift.

The 560SL was an export-only model, heading to North America, Japan and Australia, restricted to 230bhp by emissions equipment.

Barely 1000 Pagoda SLs came to the UK but the R107s were much more in evidence and are still a fairly regular sight today. Most of the nice ones seem to end up at the SL Shop in Warwickshire which furnished Classic and Sports Car with an early 350SL, a high-spec leather-trimmed 500SL and a straight-six 300SL to get a feel for how the cars developed through the 1970s and ‘80s. ![]()

In Icon Gold, with the full hubcaps, the 350SL is a real period piece to look at, a true slice of ‘70s chic compared to the slightly golf-club smugness of later variants. After the ‘Italian coffee bar’ interior look of the Pagoda, Mercedes-Benz discovered injection mouldings for its plastic dashboards in the ‘70s – colour matching them to the external hue – and offered cloth inserts in addition to the usual MB-Tex or leather for the well-shaped seats. The later SLs have veneers for the centre console, with a token sliver across the dash, but I like the honest austerity of the early car, if not the wrinkly rim of its massive steering wheel. The 300 and 500 have the same design of four-spoke helm but, somehow, the leather cover gives a much more pleasant impression as you guide them through the Warwickshire lanes.

With its headgear in place the 350SL is like a small saloon that just happens to have two seats and superb 360° vision. With their taut, beautifully tailored hoods lowered, windows up and furnace-like heaters blasting away, the 300 and 500 are cosy ways to enjoy the sights, sounds and smells of the countryside in springtime.

The 350SL, from 1974, has quite a gentle feel on the road. It rolls visibly more than the later cars, and has slower and less accurate steering, although weight and feel are good in all three. Its gearbox is there to be used if you want to extract performance; the selector works precisely in the D-S-L gate and the fluid coupling gives a positive feel to the changes compared to the seamless action of the torque-converter-equipped sport/economy transmissions in the 300 and 500. They are higher geared than the 350, in which 80mph equals 4000rpm. In all versions you must engage ‘L’ from rest or push past the resistance at the end of the long accelerator travel to get bottom gear. The 350 and 300 feel equally matched in their strong and lively, rather than startling, straight-line urge. With throttle floored the meaty 500 squats hard on its rear suspension, leaving several yards of burnt rubber in its wake and shoving you up the road with a silky thrust that keeps on coming.

The 350 V8 sounds almost fussy compared to the way the baby 300, with its hydraulic tappets, sings round to 6500rpm. I was left with the feeling that the lusty and lively six-pot R107, with all the late chassis tweaks and refinements, might just be the sweet spot of the range if you are ready to forgo V8 mystique and the period charm of the 1970s SLs.

All versions handle and ride well: substantial without being cumbersome, despite a huge steering wheel that irritated critics for 18 years, and with mild, gently understeering manners that incorporate large margins of safety. An impressive lack of scuttle shake is common to all models, combined with a useful lock that makes them easy cars to manoeuvre.

More than just transport, 50 years on the essential appeal of the R107 remains that of a compact, ‘personal’ and handy possession that manages to combine refinement and creature comforts without feeling in any way decadent, fragile or temperamental. A special car but not an exotic one: a ‘lifestyle’ automobile and timeless default statement of affluence that resonated even with those who had only a passing interest in cars. The luxury roadster everyone’s mum dreamed of – and quite a few dads too.

THE R107’S PLACE IN THE CLASSIC AND SPORTS CAR MARKET

Sam Bailey once had a ‘proper job’ in insurance but quit 13 years ago after meeting fellow Mercedes-Benz enthusiast Bruce Greetham to start the SL Shop. Today, it has 50 employees at its premises near Stratford-upon-Avon. While Bailey guides the brand direction, growing the SL customer base for buying, selling, restoring and selling parts. Greetham, who has a background in the haulage business and fell in love with Mercedes engineering when servicing his guvnor’s W124, has developed the showrooms and workshops where many of the staff are Mercedes-trained, including one veteran mechanic who pre-delivery inspected the R107s when they were new.

“There are not many 1970 SLs left,” says Greetham. “Most have been bodged and been through a lot of hands but, in the future, I think real enthusiasts will buy the early cars. There is a turn in values coming with the 40-year-old-plus, tax-exempt SLs because of the period charm.

“Having said that, the market is still strong for the late cars because they are a little bit more fuel efficient and they give you a little bit more confidence when you drive them. There will always be buyers for good 500s and 300s with the right mileage and the right history. The 300 is a super-crisp and nicely balanced car, which you can push if you really want to.”

Will R107s catch up with the Pagoda values?

“I think if you cherry-pick the right models, yes: 500SLs in the right colours with low miles are already £60-75k cars. But they have to be right.

“We have sold some heavy £80-90,000 R107s in the past 12 months. When we sell those we need to find the person who really appreciates what they are, all the preserved detail.

“We are trying to get drivers back into the right cars after COVID-19, which has changed things a bit because people are deciding if they want an investment car or something to drive and enjoy on the basis that life’s too short. The 45-60,000 miles bracket is a sweet spot here – not so low that you mind putting the miles on it, but still sharp enough to use. Even if you put 10k miles in the next 10 years on an SL like that it will be worth 25% more by then anyway.

“Some parts are getting a bit scarce and Mercedes keeps putting up the prices, which means getting average cars up to a better level is going to be prohibitive for people in the years to come. Some parts are not of the quality they were years ago but, on the other hand, some of the pattern parts can be good.”

HARDTOP’S HARD ACT TO FOLLOW

With 56,330 built from 1972-81 the SLC, the fixed-head coupé sibling of the R107 SL, was a commercial hit in its class. Yet it has always had a slight identity crisis, in that it had neither the wind-in-the-hair appeal of the SL nor the rarefied, hand-finished dignity of the W111 coupés it replaced.

Arguably the most elegant Mercedes-Benz of the 1970s, the SLC was considered to be hugely chic in period (the Americans loved them) and can even claim, in its final homologation-special-5-litre form, to have had a respectable – if brief – rallying career (read Classic & Sports Car, March). Weighing in at 3500lb and on a longer wheelbase, C107s were considered by many to be more forgiving to drive that the short and stubby two-seater SLs.

Launched at the Paris Salon in October 1971 as the 350SLC, this four-seater coupé took its visual lead from the R107 SL rather than the contemporary S-Class saloon. It shared front wings, bonnet and bootlid with the SL but with 14in let in to the R107 chassis to get extra rear-seat legroom. The glazed-in slats in its C-pillars were a visual ruse that allowed the engineers to use a smaller quarter-window that would be able to disappear into the body.

The 350SLC was soon supplemented by the 450SLC. Then, from 1974, tax-avoiding buyers could get the 280 twin-cam straight-six in the coupé. This handsome lump looked nice under the bonnet, and made the 280SLC nearly as fast as the 3.5-litre V8 – but it was nearly as thirsty too.

Most SLCs were automatics but you could order a manual on the 350 and 280 models, not that many customers did. The short-lived 1979-’81 380 and 450 5.0/500SLCs had the revised all-alloy V8s destined for the W126 S-Class. With more than 30,000 built the 225bhp 450SLC was easily the most popular SLC variant. Velour, leather, MB-Tex and tweed cloth were the trim options, but even with a £15,000 price-tag for the 450SLC (which outgunned the V12 XJ-S by £2000) you didn’t get a radio as standard.

MERCEDES-BENZ R107 SL

Sold/number built: 1971-‘89/237,387

Construction: steel monocoque

Engine: iron-block, alloy-head, dohc 2746cc or sohc 2962cc straight-six, sohc-per-bank 3499/4520cc V8, or all-alloy 3818/3839/4196/4973/5547cc V8, all with fuel injection

Max power: 180bhp @ 5700rpm to 245bhp @ 5000rpm

Max torque: 176lb ft @ 4500rpm to 297lb ft @ 3200rpm

Transmission: four/five-speed manual or three/four-speed automatic, RWD

Suspension: independent, at front by double wishbones rear semi-trailing arms; coil springs, telescopic dampers, anti-roll bar f/r

Steering: power-assisted recirculating ball

Brakes: discs, with servo; optional anti-lock from 1980

Length: 14ft 3.5in (4390mm)

Width: 5ft 8.75in (1790mm)

Height: 4ft 2.5in (1300mm)

Wheelbase: 8ft (2460mm)

Weight: 3307-3781lb (1500-1715kg)

0-60mph: 9.3-7.1 secs

Top speed: 126-140mph Mpg 15.4

Price new: £6995 (350SL, 1973)

Price now: £15-60,000

GRAB YOURSELF A SLICE OF CLASSIC AND SPORTS CAR ROYALTY

The 1973 350SL discussed by Classic and Sports Car here is available today and ready for a new home. Sitting in the 50,000 mile bracket, this is a car that as Sales Director Bruce Greetham pointed out, will relish another 10,000 miles and still increase by 25% in value.

Available Here.

![]()

Share With Your Fellow Enthusiasts

More from Journal

CARE

THE ULTIMATE CERTIFIED SERVICING INVESTMENT PLAN

Your ownership journey matters to us, which is why we have created a simple certified servicing investment plan, tailored to your individual needs and aspirations.

Start investing today and our dedicated CARE team will work with you to increase the value and enjoyment you receive from your vehicle.

STAY IN TUNE WITH SLSHOP MOMENTS

As part of SLSHOP’s community of enthusiasts, you’ll be the first to hear about events and tours, key product offers, exciting stories from owners around the world and of course… our latest additions to the showroom. So, be the first to know and you might just sneak a car on your driveway or take your car’s condition to new heights with our exclusive replacement parts.

Or, visit SLSHOP Journal