60 years young in 2023, the gorgeous Mercedes-Benz ‘Pagoda’ retains a unique appeal among Stuttgart’s flagship SL line.

Article: Classic & Sports Car Magazine

Words: Martin Buckley/Nick Kisch

Photography: Luc Lacey

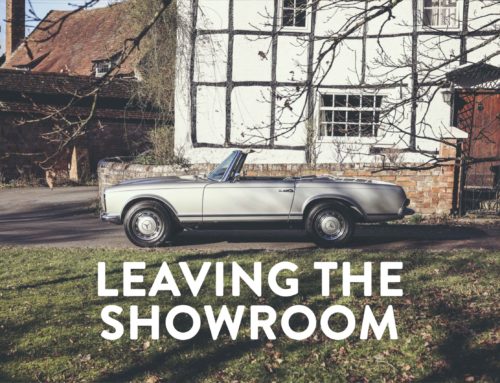

Timeless is an overused adjective when it comes to writing about old cars, but the Mercedes-Benz SLs of 1963-’71 are among a select group of vehicles that are truly deserving of it. People who were not even born when this magazine first started writing about W113 SLs in the early 1980s – and perhaps have only a passing interest in old cars – instinctively recognize the 230/250/280SLs as objects of desire that transcend fleeting fashion.

Part sports car, part open-topped GT, this was the SL that set the tone for all subsequent Mercedes two-seaters. Fast but not aggressive, luxurious and easy to drive, it was a usefully compact and agile glamour machine that fulfilled the roles of Bond Street cruiser and intercity express with equal aplomb. This is a car that has simply never gone out of fashion with both men and women, but its reputation as the ultimate accessory for a leading lady is well earned. On screen it looked as desirable in supporting with Julie Christie (Darling) and Audrey Hepburn (Two for the Road) in its ‘60s heyday as it did with Helen Mirren behind the wheel in The Long Good Friday, 10 years after the last of almost 50,000 cars was built.

In all its forms, the W113 SL was enough of a driver’s car to win the respect of ‘serious motorist (Stirling Moss loved his 250SL), while catching the attention of those wealthy individuals looking for a fun yet prestigious second car: a car that would keep its looks and hold its value long after its more ephemerally exotic ‘60s rivals had fallen by the wayside.

For the rest of us, the Pagodas were relatable in a way their predecessors never had been, moving the Benz sports car image away from the realm of the handbuilt, spaceframe-chassis 3-litre supercar (or the overbodied 1.9-litre boulevardier) into that of a practical grand-touring machine that made clever use of the latest production saloon technology.

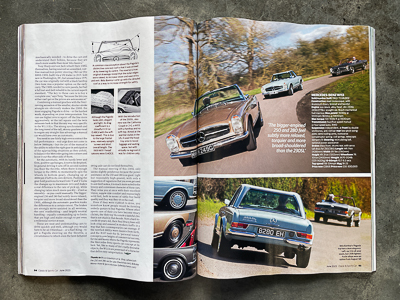

It was the shape that first captured buyers’ imaginations at the Geneva Salon in 1963. With its wide grille and bespoke Bosch headlights, the 230 plotted a perfect visual course between the machismo of the 300SL and the purely feminine appeal of the 190. Riding on a wider track than the giant MkX Jaguar, Paul Bracq’s shape had elegance and dignity combined with a certain pugnaciousness that spoke of the high levels of roadholding – on fat, specially designed asymmetric Continental tyres – that were at the heart of the car’s design philosophy.

Mercedes’ prodigiously talented chief engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut made the point of the car’s launch by lapping a 230SL on the Montreux circuit to within 0.2 secs of the time set by Mike Parkes in a Ferrari 250GT SWB. Eugen Bohringer’s victory in the 1963 Spa-Sofia-Liége rally added further weight to the Pagoda’s credentials as a ‘real’ sports car.

The unofficial ‘Pagoda’ epithet for these cars derives, of course, from the shape of the roof. No other open-topped machine is so closely defined by the form of its (optional) hardtop, a beautifully engineered removable roof designed to be both strong and afford superb 360° vision. The concave design allowed room for the deep windows – giving 38% more glass area than the 90SL – and easy ingress and exit. Attached by four chromed handles, it was weather-and wind-tight but fiendishly heavy.

The aim of the designers was to produce a sporty two-seater that demanded less of its driver than the aggressive 300SL, but was much livelier – and handled better – than the anaemic 190SL. It was comfier and more convenient, too, with supple suspension, superbly designed and figure-hugging seats, and a magnificent hood. Options included responsive power steering (the best of its kind at the time, even if the wheel seemed too big) and a user-friendly four-speed automatic transmission that in the end enhanced the driver appeal of the Pagoda, rather than detracting from it.

Mercedes thought hard about ventilation and ergonomics, too, with a clearly designed – if slightly flashy – dashboard (often described as a ‘coffee bar’), and a multi-function column stalk for indicators, flashing and wipers that must have been among the first of its type.

In essence, the 1963-’67 230SL was a 220SE ‘Fintail’ saloon under the skin – the prototypes even wore ‘220SL’ badging – but with a larger, four-main-bearing 2306cc engine. It used a six-plunger Bosch injection pump, driven at half engine speed, and a slightly higher-lift camshaft for a healthy 150bhp, a near-120mph maximum speed and easy 100mph cruising.

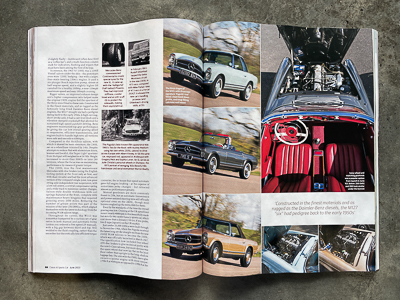

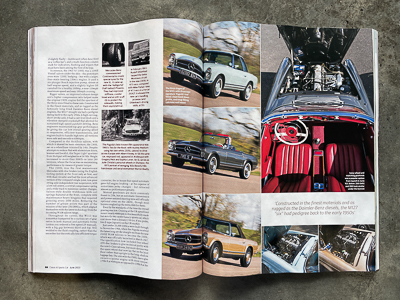

Bigger valves, an improved exhaust design and a higher compression ratio helped make the original 230SL engine feel the sportiest of the three sizes fitted to these cars. Constructed in the finest materials, and as rugged as the famously long-lived Daimler-Benz diesel engines, the M127 straight-six had a pedigree dating back to the early 1950s. A high-revving, short-stroke unit, it had a cast-iron block and a vibration-damped crankshaft that allowed for sustained high-speed autobahn driving. Benz engineers maintained top-gear performance by giving the car low overall gearing allied to responsive, efficient transmissions, and engines built to handle high revs: all versions were safe and smooth to 6500rpm.

Compared to the Heckflosse saloon, with which it shared its basic structure, the 230SL sat on a wheelbase trimmed by 14in. Despite attempts to reduce flab with aluminium doors, bonnet and bootlid, this ‘Super Light’ sportster from Stuttgart still weighed in at 2670lb. Weight increased to more than 3000lb on later 280 versions, where the focus was on maintaining performance by means of greater torque.

The 230SL was the first mainstream Mercedes with disc brakes (using the English Girling system at the front only at first, and with dual circuits) and had the most advanced version of the company’s single-joint, low-pivot swing-axle independent rear suspension, with a low roll centre, a central compensator spring and a wide track to minimize camber changes. Saloon-style double wishbones with coil springs featured at the front, complete with maintenance-heavy kingpins that required greasing every 2000 miles. Reducing the number of grease points was part of the mission of the later 250/280SLs, which aligned themselves with the latest technology from the incoming W108 saloon range.

Throughout its career, the W113 was somewhat hampered by a curious set of gear ratios in both manual and automatic forms (unless you ordered a five-speed ZF manual), with a big gap between third and top. Still wedded to the fluid coupling, rather than the smoother but theoretically less efficient torque converter, the in-house four-speed automatic gave full engine braking – at the expense of sometimes jerky changes – but extracted almost no performance penalty.

Manual gearboxes are more commonly found in 230s, but an automatic transmission and power-assisted steering were still officially optional even on the 280SL, though most buyers coughed up the extra £800 for them.

Even by the standards of the time the overall gearing was low. Cruising at the UK speed limit meant nearly 4000rpm in this beautifully made but strictly two-seater luxury sports car, which cost more than a Jensen C-V8 (or, if you prefer, two E-type Jaguars) on the UK market.

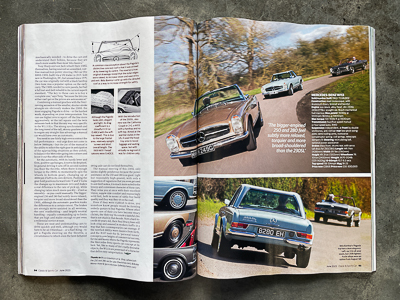

Just under 20,000 230SLs were built through to November 1966, when the Pagoda received the latest long-stroke straight-six from the new 250SE W108 saloons to become the 250SL which was officially launched in March 1967. The specification now included four-wheel ATE disc brakes to give technical parity with the new S-Class saloons, but more obvious was the spare wheel that now lay flat on the boot floor rather than upright in the long, shallow luggage bay. The aim with the 250SL was to give owners a quieter engine with more torque: 179lb ft at 4500rpm as opposed to 159lb ft at the same engine speed in the freer-revving 230SL. Uprated to seven main bearings to cope with the increased stroke, the 250 powerplant featured a larger oil pump, bigger valves and an improved throttle linkage.

Over a short run of 10 months and 5186 cars, the 250SL acquired certain detail trim features – such as full wheel covers rather than simple hubcaps, a different steering-wheel boss and new rear-light lenses, among other things more commonly associated with 280SL.

Launched with little fanfare at Brussels in January 1986, the 280SL was more than 200lb heavier than the original 1963 car, but had extra 10bhp and 11% more torque than the 250 from an engine whose additional 282cc was achieved by siamesed cylinder bores. Five seconds quicker to 100mph and good for 124mph flat-out, the 280SL was definitively faster than its predecessors, but was still hard car to categorize or compare with anything else as a £5000 two-seater. But buyers didn’t care, and bought almost 24,000 of them through to the end of production in February 1971.

Today, the popularity, recognition and acceptance of the Pagoda family is even greater that it was when they were current, with the 280s commanding a huge premium over the earlier models, particularly the 230s.

“The 230SLs are bought out of enthusiasm,” confirms Bruce Greetham of the SL Shop, “whereas the 280SLs are more of a financial decision for people because, in the end, they both cost the same to restore. In fact, people tend to buy 230s and 250s where someone else has already put in the money, rather than try to restore them – not least because some of the trim for the early cars is much rarer.”

Looking around the SL Shop’s stock, the headcount favours the Pagoda over the R107s. “Where the R107s have gained value, in some cases customers have traded up to a Pagoda,” explains Bruce. “ Our problem is instilling the confidence in people – who are not always very mechanically minded – to drive the cars and understand their foibles, because they are much more usable than most “60s classics.”

Tony Sharp and son Jack rebuilt their 230SL themselves, having sourced an unwelded, rust-free manual/non-power-steering 1963 car (the 800th 230SL built) via a UK trader in 2019. Sold new in Washington, DC, but unused since 1979, the car was originally red with a black hardtop (two-tone was a popular option on the early cars). The 230SL needed no new panels, but had a full nut-and-bolt rebuild to its current superb standard. “The key to these cars is to buy a complete one,” says Tony, ”because the bits you either can’t get or the prices are astronomical.”

Combining a manual gearbox with the freer-revving sensation of the smaller, shorter-stroke straight-six obviously makes the 230SL the most engaging Pagoda to drive – or the hardest work, depending on your interpretation. You can use higher revs to squirt off the line more aggressively, as the tail squats and the twin exhausts bark in that throaty way very specific to the W113 SLs. The strong synchromesh and the long travel of the tall, skinny gearlever tend to negate any straight-line advantage a manual car would have over an automatic.

You need to use fairly high revs to extract the full performance – real urge does not come in below 3000rpm – but the joy of the manual is the ability to select the right gear in anticipation of the approaching situations as they unfold, to balance the Mercedes going into corners and boost it out the other side of them.

Yet the automatic, with its handy lever and firm, positive upchanges, is not to be despised. In general driving it sets off in second (unless you floor the throttle, when there is enough torque in the 280SL to momentarily spin the wheels in bottom gear), changing up at 4000rpm if left to its own devices. Pushing the gear-hold positions forward into ‘3’ and ‘2’ locks the changes up to maximum revs and makes a real difference to the rate of pick-up, while changing ratios much more quickly – if not so smoothly – as you could manually. The bigger engine 250 and 280 feel subtly more relaxed, torquier and more broad-shouldered that the 230SL, although the automatic gearbox masks the differences to a certain extent. The brakes are strongly servo-assisted in all versions, the cars’ roadholding – and largely neutral handling – equally commanding up to limits that are high and stable enough to put even a millennial novice at ease.

These are neat and undemanding cars to drive quickly and well, although you would have to be an Uhlenhaunt – or a Karl Kling – to get a Pagoda steering on the throttle, a circumstance to which even the best-behaved swing-axle cars do not lend themselves.

The manual steering of this 230SL only seems slightly ponderous because the power assistance on the 250 and 280 is so good. Light but reasonably high-geared, with only a suggestion of vagueness that you soon get used to and don’t notice, it is much more suited to the breezy and convenient character of these cars. They relax you at once with their excellent vision, supple ride comfort and reassuringly solid feel, both in terms of rattle-free build quality and the way they sit on the road.

Even if they were rubbish to drive, you somehow know people would be forming orderly queues to buy Pagodas. Where other sports cars of their era have become weary clichés, the dish-top’ SLs exude a tasteful chic that is not stuck in that decades. Now a hard-to-credit 60 years old, their Paul Bracq lines still look crisp and assured in modern traffic in a way that few contemporaries can manage. If the rarefied 300SLs were classics from birth, and the R107 took the SL ‘personal luxury’ concepts to new heights of commercial success, for me and many others the Pagoda represents the Mercedes-Benz sports car concept at its best. Yet, like so many of life’s really desirable objects, the W113s are possessed of a character that defies easy categorisation.

60 years young in 2023, the gorgeous Mercedes-Benz ‘Pagoda’ retains a unique appeal among Stuttgart’s flagship SL line.

Article: Classic & Sports Car Magazine

Words: Martin Buckley/Nick Kisch

Photography: Luc Lacey

Timeless is an overused adjective when it comes to writing about old cars, but the Mercedes-Benz SLs of 1963-’71 are among a select group of vehicles that are truly deserving of it. People who were not even born when this magazine first started writing about W113 SLs in the early 1980s – and perhaps have only a passing interest in old cars – instinctively recognize the 230/250/280SLs as objects of desire that transcend fleeting fashion.

Part sports car, part open-topped GT, this was the SL that set the tone for all subsequent Mercedes two-seaters. Fast but not aggressive, luxurious and easy to drive, it was a usefully compact and agile glamour machine that fulfilled the roles of Bond Street cruiser and intercity express with equal aplomb. This is a car that has simply never gone out of fashion with both men and women, but its reputation as the ultimate accessory for a leading lady is well earned. On screen it looked as desirable in supporting with Julie Christie (Darling) and Audrey Hepburn (Two for the Road) in its ‘60s heyday as it did with Helen Mirren behind the wheel in The Long Good Friday, 10 years after the last of almost 50,000 cars was built.

In all its forms, the W113 SL was enough of a driver’s car to win the respect of ‘serious motorist (Stirling Moss loved his 250SL), while catching the attention of those wealthy individuals looking for a fun yet prestigious second car: a car that would keep its looks and hold its value long after its more ephemerally exotic ‘60s rivals had fallen by the wayside.

For the rest of us, the Pagodas were relatable in a way their predecessors never had been, moving the Benz sports car image away from the realm of the handbuilt, spaceframe-chassis 3-litre supercar (or the overbodied 1.9-litre boulevardier) into that of a practical grand-touring machine that made clever use of the latest production saloon technology.

It was the shape that first captured buyers’ imaginations at the Geneva Salon in 1963. With its wide grille and bespoke Bosch headlights, the 230 plotted a perfect visual course between the machismo of the 300SL and the purely feminine appeal of the 190. Riding on a wider track than the giant MkX Jaguar, Paul Bracq’s shape had elegance and dignity combined with a certain pugnaciousness that spoke of the high levels of roadholding – on fat, specially designed asymmetric Continental tyres – that were at the heart of the car’s design philosophy.

Mercedes’ prodigiously talented chief engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut made the point of the car’s launch by lapping a 230SL on the Montreux circuit to within 0.2 secs of the time set by Mike Parkes in a Ferrari 250GT SWB. Eugen Bohringer’s victory in the 1963 Spa-Sofia-Liége rally added further weight to the Pagoda’s credentials as a ‘real’ sports car.

The unofficial ‘Pagoda’ epithet for these cars derives, of course, from the shape of the roof. No other open-topped machine is so closely defined by the form of its (optional) hardtop, a beautifully engineered removable roof designed to be both strong and afford superb 360° vision. The concave design allowed room for the deep windows – giving 38% more glass area than the 90SL – and easy ingress and exit. Attached by four chromed handles, it was weather-and wind-tight but fiendishly heavy.

The aim of the designers was to produce a sporty two-seater that demanded less of its driver than the aggressive 300SL, but was much livelier – and handled better – than the anaemic 190SL. It was comfier and more convenient, too, with supple suspension, superbly designed and figure-hugging seats, and a magnificent hood. Options included responsive power steering (the best of its kind at the time, even if the wheel seemed too big) and a user-friendly four-speed automatic transmission that in the end enhanced the driver appeal of the Pagoda, rather than detracting from it.

Mercedes thought hard about ventilation and ergonomics, too, with a clearly designed – if slightly flashy – dashboard (often described as a ‘coffee bar’), and a multi-function column stalk for indicators, flashing and wipers that must have been among the first of its type.

In essence, the 1963-’67 230SL was a 220SE ‘Fintail’ saloon under the skin – the prototypes even wore ‘220SL’ badging – but with a larger, four-main-bearing 2306cc engine. It used a six-plunger Bosch injection pump, driven at half engine speed, and a slightly higher-lift camshaft for a healthy 150bhp, a near-120mph maximum speed and easy 100mph cruising.

Bigger valves, an improved exhaust design and a higher compression ratio helped make the original 230SL engine feel the sportiest of the three sizes fitted to these cars. Constructed in the finest materials, and as rugged as the famously long-lived Daimler-Benz diesel engines, the M127 straight-six had a pedigree dating back to the early 1950s. A high-revving, short-stroke unit, it had a cast-iron block and a vibration-damped crankshaft that allowed for sustained high-speed autobahn driving. Benz engineers maintained top-gear performance by giving the car low overall gearing allied to responsive, efficient transmissions, and engines built to handle high revs: all versions were safe and smooth to 6500rpm.

Compared to the Heckflosse saloon, with which it shared its basic structure, the 230SL sat on a wheelbase trimmed by 14in. Despite attempts to reduce flab with aluminium doors, bonnet and bootlid, this ‘Super Light’ sportster from Stuttgart still weighed in at 2670lb. Weight increased to more than 3000lb on later 280 versions, where the focus was on maintaining performance by means of greater torque.

The 230SL was the first mainstream Mercedes with disc brakes (using the English Girling system at the front only at first, and with dual circuits) and had the most advanced version of the company’s single-joint, low-pivot swing-axle independent rear suspension, with a low roll centre, a central compensator spring and a wide track to minimize camber changes. Saloon-style double wishbones with coil springs featured at the front, complete with maintenance-heavy kingpins that required greasing every 2000 miles. Reducing the number of grease points was part of the mission of the later 250/280SLs, which aligned themselves with the latest technology from the incoming W108 saloon range.

Throughout its career, the W113 was somewhat hampered by a curious set of gear ratios in both manual and automatic forms (unless you ordered a five-speed ZF manual), with a big gap between third and top. Still wedded to the fluid coupling, rather than the smoother but theoretically less efficient torque converter, the in-house four-speed automatic gave full engine braking – at the expense of sometimes jerky changes – but extracted almost no performance penalty.

Manual gearboxes are more commonly found in 230s, but an automatic transmission and power-assisted steering were still officially optional even on the 280SL, though most buyers coughed up the extra £800 for them.

Even by the standards of the time the overall gearing was low. Cruising at the UK speed limit meant nearly 4000rpm in this beautifully made but strictly two-seater luxury sports car, which cost more than a Jensen C-V8 (or, if you prefer, two E-type Jaguars) on the UK market.

Just under 20,000 230SLs were built through to November 1966, when the Pagoda received the latest long-stroke straight-six from the new 250SE W108 saloons to become the 250SL which was officially launched in March 1967. The specification now included four-wheel ATE disc brakes to give technical parity with the new S-Class saloons, but more obvious was the spare wheel that now lay flat on the boot floor rather than upright in the long, shallow luggage bay. The aim with the 250SL was to give owners a quieter engine with more torque: 179lb ft at 4500rpm as opposed to 159lb ft at the same engine speed in the freer-revving 230SL. Uprated to seven main bearings to cope with the increased stroke, the 250 powerplant featured a larger oil pump, bigger valves and an improved throttle linkage.

Over a short run of 10 months and 5186 cars, the 250SL acquired certain detail trim features – such as full wheel covers rather than simple hubcaps, a different steering-wheel boss and new rear-light lenses, among other things more commonly associated with 280SL.

Launched with little fanfare at Brussels in January 1986, the 280SL was more than 200lb heavier than the original 1963 car, but had extra 10bhp and 11% more torque than the 250 from an engine whose additional 282cc was achieved by siamesed cylinder bores. Five seconds quicker to 100mph and good for 124mph flat-out, the 280SL was definitively faster than its predecessors, but was still hard car to categorize or compare with anything else as a £5000 two-seater. But buyers didn’t care, and bought almost 24,000 of them through to the end of production in February 1971.

Today, the popularity, recognition and acceptance of the Pagoda family is even greater that it was when they were current, with the 280s commanding a huge premium over the earlier models, particularly the 230s.

“The 230SLs are bought out of enthusiasm,” confirms Bruce Greetham of the SL Shop, “whereas the 280SLs are more of a financial decision for people because, in the end, they both cost the same to restore. In fact, people tend to buy 230s and 250s where someone else has already put in the money, rather than try to restore them – not least because some of the trim for the early cars is much rarer.”

Looking around the SL Shop’s stock, the headcount favours the Pagoda over the R107s. “Where the R107s have gained value, in some cases customers have traded up to a Pagoda,” explains Bruce. “ Our problem is instilling the confidence in people – who are not always very mechanically minded – to drive the cars and understand their foibles, because they are much more usable than most “60s classics.”

Tony Sharp and son Jack rebuilt their 230SL themselves, having sourced an unwelded, rust-free manual/non-power-steering 1963 car (the 800th 230SL built) via a UK trader in 2019. Sold new in Washington, DC, but unused since 1979, the car was originally red with a black hardtop (two-tone was a popular option on the early cars). The 230SL needed no new panels, but had a full nut-and-bolt rebuild to its current superb standard. “The key to these cars is to buy a complete one,” says Tony, ”because the bits you either can’t get or the prices are astronomical.”

Combining a manual gearbox with the freer-revving sensation of the smaller, shorter-stroke straight-six obviously makes the 230SL the most engaging Pagoda to drive – or the hardest work, depending on your interpretation. You can use higher revs to squirt off the line more aggressively, as the tail squats and the twin exhausts bark in that throaty way very specific to the W113 SLs. The strong synchromesh and the long travel of the tall, skinny gearlever tend to negate any straight-line advantage a manual car would have over an automatic.

You need to use fairly high revs to extract the full performance – real urge does not come in below 3000rpm – but the joy of the manual is the ability to select the right gear in anticipation of the approaching situations as they unfold, to balance the Mercedes going into corners and boost it out the other side of them.

Yet the automatic, with its handy lever and firm, positive upchanges, is not to be despised. In general driving it sets off in second (unless you floor the throttle, when there is enough torque in the 280SL to momentarily spin the wheels in bottom gear), changing up at 4000rpm if left to its own devices. Pushing the gear-hold positions forward into ‘3’ and ‘2’ locks the changes up to maximum revs and makes a real difference to the rate of pick-up, while changing ratios much more quickly – if not so smoothly – as you could manually. The bigger engine 250 and 280 feel subtly more relaxed, torquier and more broad-shouldered that the 230SL, although the automatic gearbox masks the differences to a certain extent. The brakes are strongly servo-assisted in all versions, the cars’ roadholding – and largely neutral handling – equally commanding up to limits that are high and stable enough to put even a millennial novice at ease.

These are neat and undemanding cars to drive quickly and well, although you would have to be an Uhlenhaunt – or a Karl Kling – to get a Pagoda steering on the throttle, a circumstance to which even the best-behaved swing-axle cars do not lend themselves.

The manual steering of this 230SL only seems slightly ponderous because the power assistance on the 250 and 280 is so good. Light but reasonably high-geared, with only a suggestion of vagueness that you soon get used to and don’t notice, it is much more suited to the breezy and convenient character of these cars. They relax you at once with their excellent vision, supple ride comfort and reassuringly solid feel, both in terms of rattle-free build quality and the way they sit on the road.

Even if they were rubbish to drive, you somehow know people would be forming orderly queues to buy Pagodas. Where other sports cars of their era have become weary clichés, the dish-top’ SLs exude a tasteful chic that is not stuck in that decades. Now a hard-to-credit 60 years old, their Paul Bracq lines still look crisp and assured in modern traffic in a way that few contemporaries can manage. If the rarefied 300SLs were classics from birth, and the R107 took the SL ‘personal luxury’ concepts to new heights of commercial success, for me and many others the Pagoda represents the Mercedes-Benz sports car concept at its best. Yet, like so many of life’s really desirable objects, the W113s are possessed of a character that defies easy categorisation.

More from Journal

CARE

THE ULTIMATE CERTIFIED SERVICING INVESTMENT PLAN

Your ownership journey matters to us, which is why we have created a simple certified servicing investment plan, tailored to your individual needs and aspirations.

Start investing today and our dedicated CARE team will work with you to increase the value and enjoyment you receive from your vehicle.

STAY IN TUNE WITH SLSHOP MOMENTS

As part of SLSHOP’s community of enthusiasts, you’ll be the first to hear about events and tours, key product offers, exciting stories from owners around the world and of course… our latest additions to the showroom. So, be the first to know and you might just sneak a car on your driveway or take your car’s condition to new heights with our exclusive replacement parts.

Or, visit SLSHOP Journal