Six decades ago, one of the most elegant, and dare we say iconic, open-top machines ever made was revealed at the prestigious Geneva Salon. The Pagoda SL arrived amid some of the most beautiful machinery ever to grace our roads – including the Jaguar E-type and Porsche 911. It nevertheless managed to trade blows with formidable foes and today has evolved into one of the most timelessly elegant and collectible classic cars in existence.

To celebrate its legacy, and continued popularity, we’ve amassed 60 top facts that sum up the W113, the SL generation that arguably more than any other, managed to distil the essence of this renowned open-top Mercedes-Benz.

TOP 60 MERCEDES PAGODA FACTS

1. In the 1960s, the average car owner – especially in Europe – was considered lucky if their machine came with a passenger side wing mirror or a radio. The W113 was an expensive car for sure, but even factoring this in, it was astonishingly well equipped. An automatic transmission and power steering might have been optional (though almost everyone ticked the boxes) but its fuel-injected, seven bearing (from 1966 in the 250 and 280) engines weren’t.

2. The single pivot rear end, the staple of previous Mercedes-Benz offerings, was reused for the W113, but not without trying to address some of its short comings. Under extreme conditions, the rear could jack up, leading to a sudden break in traction. The short-term solution M-B engineers settled upon was to develop a brand-new radial-ply tyre – in conjunction with tyre firms Continental and Firestone. The new tyre offered increased grip from a stiffer side wall, as per a radial, while maintaining much of the predictable breakaway of a cross ply.

3. Disc brakes all round were added for the larger engine 250 and 280 SLs. The 230 made do – perfectly well – with a disc and drum combo.

4. The Pagoda was the first SL to be developed by engineers who didn’t have to consider motorsport. The 1955 Le Mans disaster had shaken Mercedes-Benz, with its subsequent withdrawal from all factory-backed competition meaning there was no need to factor racing into the W113’s DNA.

5. One of the leading lights in passive safety at Stuttgart was M-B engineer Béla Barényi. Up to 1951, cars were still made outwardly as strong as possible, as it was thought safer for passengers. Barényi turned this idea on its head, making deformable outer sections of bodywork around a solid passenger safety cell – in other words, inventing the crumple zone.

6. Although circuit racing was out, Mercedes-Benz did continue to back select rally competitors. One of which was M-B works driver Eugen Böhringer. Deciding that the new more compact SL would be the ideal candidate for the gruelling Spa-Sofia-Liège event, Böhringer managed to convince M-B competitions manager Karl Kling to provide a suitably modified 230SL. This near standard 230SL managed to win the event against stiff competition from BMC’s Austin-Healey 3000, silencing critics of the new ‘softer’ SL in the process.

7. The Mercedes-Benz staple of increasing safety through mechanical innovation had taken giant leaps forward during the 1950s and much of what had been learned through crash-testing was implemented for the W113. The 280SL’s padded steering wheel centre and dashboard top merely the most obvious nods to passenger safety. There would also be head rests (on US models) and anchors for three-point safety belts.

8. The Pagoda design team was led by Friedrich Geiger, yet it’s thought likely designer Paul Bracq and engineer Béla Barényi also contributed heavily to the signed-off silhouette. Yet, as is so often the case with a design-house creation, the precise penmanship that lead to the final showroom appearance of the W113 is up for debate.

9. Few machines can boast as many glamorous alumni as the Pagoda SL. Songwriters John Lennon and Tina Turner both had one, alongside the ‘King’s’ widow, Priscilla Presley. More contemporary celebrity owners include F1 driver David Coulthard, former Spice Girl Emma Bunton and Harry Styles.

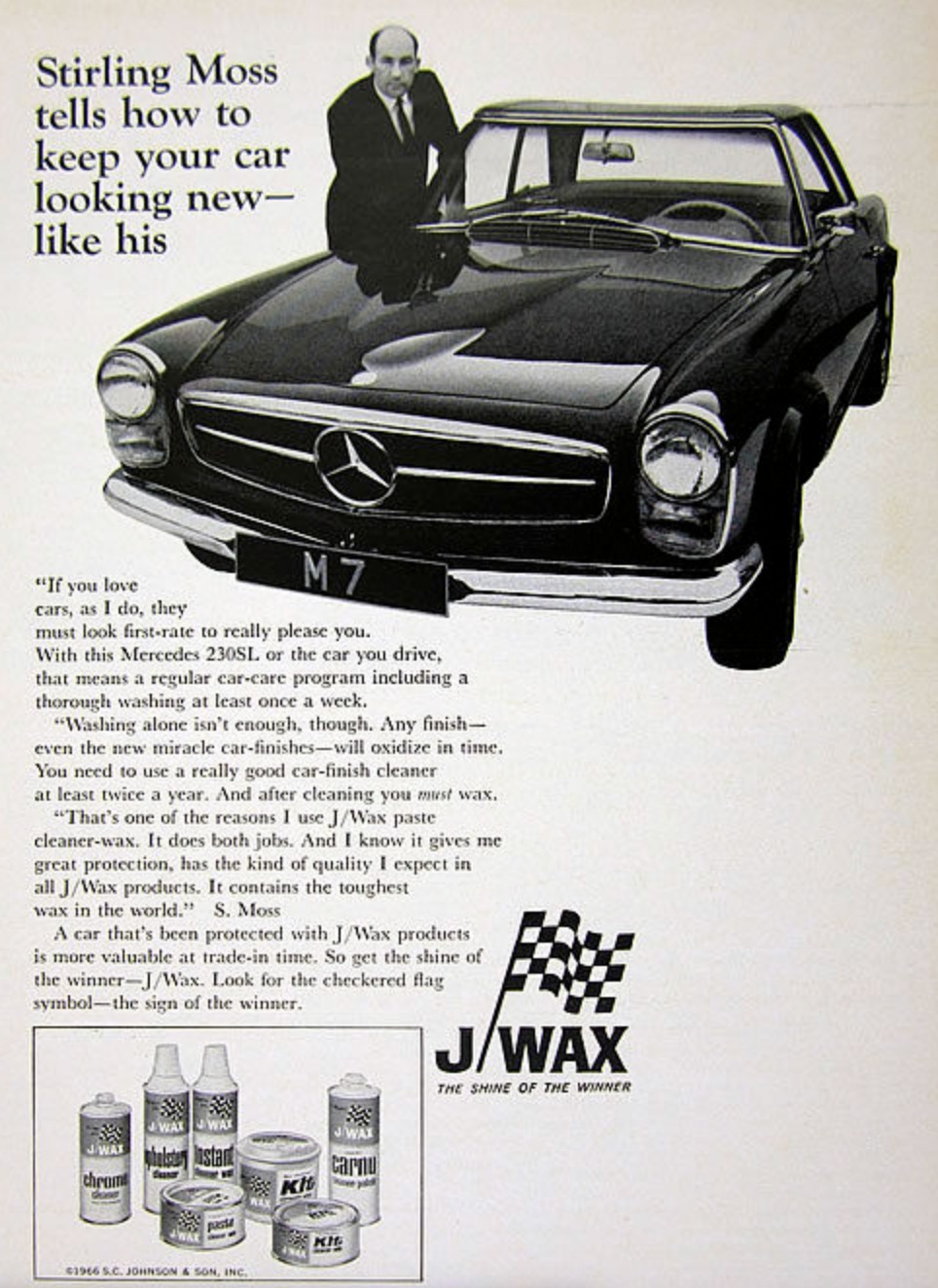

10. Despite their day job – or rather because of it – racing drivers also chose to ensconce themselves in the quiet style of this SL. All-time greats Juan Manual Fangio and arch rival Sir Stirling Moss are both counted among former owners.

11. Having spent four years in development, the W113 was unveiled to the world at the Geneva Salon in March of 1963. Two years earlier, the same event had seen the debut of another automotive icon of the era, the Jaguar E-type and the seminal Porsche 911 would be seen just 12 months later.

12. One of the few curves found on the straight-edged W113 was responsible for its popular nickname. The near unique concave bow of the hard-top roof – designed by engineer Béla Barényi to add strength, improve visibility and aid access – led many to compare it to the similarly-shaped roofs of ancient Asian buildings – after that, the name Pagoda stuck.

13. Suitably impressed with its new 6.3-litre V8 engine – developed for the magnificent 600 ‘Grosser’ saloon – the manager of the M-B experimental department Erich Waxenberger, had one fitted to a contemporary S-Class. The result was the astonishing 300SEL 6.3, but what’s less known, is that the same engine was fitted to a Pagoda. The resulting 250bhp, 140mph SL was good for a Nürburgring Nordschleife lap time of 10 mins 30 seconds.

14. In its eight-year production run, the W113 sold 48,912 units – the mass majority of which were 280 SLs.

15. A whopping 77 per cent of all Pagodas sold were specified with the optional four-speed automatic transmission. A figure that heavily implied who SL customers were and what they wanted from their open-top Mercedes-Benz experience. Information that Stuttgart would take into developing the W113’s replacement – the R107 – which was rarely offered with a manual.

16. In 1967, Mercedes-Benz showcased a Pagoda 2+2 coupe – unofficially known as the ‘California Coupe’ – at that year’s Geneva Motor Show. The space liberated by losing the soft-top roof was occupied by a pair of small rear seats.

17. During one of the W113’s press launches, at the compact 0.7-mile Montroux circuit, M-B legend and motorsport engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut – demonstrating the car, despite being 57-years old – managed a lap of 47.5 seconds. Also testing on the circuit that same day was Ferrari test engineer and future F1 racer Mike Parkes. Parkes managed to get his Ferrari 250GT Berlinetta around the same track, on the same day, in 47.3 seconds – just 0.2 seconds faster than Uhlenhaut in his far less powerful 230SL.

18. The 230SL was the first Mercedes-Benz road car to be fitted with disc brakes, but they weren’t German, they came from Britain. Girling’s disc brake system was used – together with a Master-Vac servo to power its front discs.

19. In 1968, another experimental engine was fitted to a Pagoda, this time a 203bhp Wankel. The test mule, designated W33-29, was tested for nearly 70,000km before the project was scrapped.

20. At launch, and for a long time during its production, some SL fans complained that the W113 had ‘gone soft’. A real sportscar with power steering was deemed a contradiction. Missing the point entirely that the powered recirculating ball system was actually quicker by half a turn than its manual alternative.

21. When the 250SL was introduced in 1967 it came with the new seven bearing engine from the 250SE saloon. Its piston area was no greater than that of the 230’s, the extra displacement coming from an increase in stroke. This lowered the engine’s powerband when compared to the peakier 230SL’s. Some loved its more accessible grunt (10% more torque), while others missed the high-revving nature of its smaller-displacement sibling.

22. The four-speed automatic transmission fitted to the W113 was well ahead of its time when it came to driver interaction. Fully automatic mode was achieved by slotting the lever into ‘4’. Dropping it down to ‘3’ locked out top gear, allowing the engine to rev out in third. The same was true of ‘2’, but it also forced first gear take offs – in any other position, the car took off in second.

23. Sir Stirling Moss, no stranger to Daimler-Benz of course, had his own 230SL converted with the bigger M129 engine from the 250SE. The former Mille Miglia winner loved his SL but, somewhat unsurprisingly, lusted after more power. He went to great pains to have his W113 converted privately, just before the factory did the job for him when it released the 250SL in 1967.

24. The Pagoda was the first mass-produced SL to be entirely powered by six-cylinder engines. There wouldn’t be another four-cylinder ‘SL’ until the SLK230, some three decades later, but at least it was supercharged.

25. Interestingly, 230SL and 280SL drivers were clearly very different. Made clear by the figures, three-quarters of 230SL buyers chose the manual transmission, while a staggering 90 per cent of the 280SL’s first owners went for the optional automatic.

26. The Pagoda was a technical and styling masterpiece but it certainly didn’t come cheap. The cost of a 280SL with power steering and automatic transmission options (as most came) in 1969, was nearly £4500. That was twice the cost of a 4.2-litre Jaguar E-type and equivalent to nearly £80k today.

27.

This generation of SL came in four distinct body styles. There was the Roadster, Coupe, Coupe 2/2 and Coupe Convertible. Essentially, all had a soft-top roof, except for the 2/2 that replaced the whole mechanism with a pair of rear seats. There was also the option of a rear ‘jump seat’ for a solitary transverse rear passenger, just to confuse matters.

28. Federal spec Pagodas differ a surprising amount from their European cousins. The separate sealed beam headlights are totally different, as are the milder camshafts and rubber-tipped over-riders. SLs destined for the United States also carried side wing reflectors, hazard lights and seat head rests. Rear axles had a lower ratio too. While some of these alterations are easily reversed, many aren’t. Converting to right-hand drive, for example, is perilously expensive and complicated.

29. In September 1964, the vertical spare wheel well was removed from the boot, with the spare tyre now stowed horizontal – significantly reducing luggage space in the process.

30. The 250SL is the rarest model of the three W113s. A total of 19,831 230SLs were built from 1963 to January 1967. The stop-gap 250SL was only made for one year (1967) with just 5196 made. The 280SL was the most numerous, with 23,885 built between December 1967 and the end of W113 production in March 1971.

31. Of the near 49,000 W113s made, almost half that number were sold to customers in the United States.

32. The wheelbase of the W113 is identical to its 190SL and 300SL predecessors at 2400mm.

33. Although the basic engine block used in all the W113s was the same as the W111 saloon’s, the more sporting application in the SL lead to a number of revisions. The most notable was the six-plunger injection pump – as opposed to the two plungers of the W111. This allowed more direct injection of fuel into the pre-heated (by surrounding coolant) intake ports, just ahead of the valves and cylinder – greatly increasing power.

34. Despite its engine developing 10 percent more torque and an increased displacement – from its lengthened stoke – the power the 250SL engine developed was essentially the same as its predecessor at 150bhp. The 250SL also had a slightly slower top speed than the 230, due to its increased weight – largely down to the new quad disc brakes and rear-axle compensator.

35. In typically understated fashion, the only distinguishing detail of the range-topping 280SL, apart from its rear model badges, were its new hubcaps.

36. The five-speed manual S5-20 transmission that was added from May 1966 – as an optional alternative to the default four-speed – was manufactured by Zahnradfabrik Friedrichshafen, better known as ZF. Just 882 customers opted for this five-speed box, making it an extremely rare and desirable factory option today.

37. The slight bulge in the bonnet of the W113 isn’t just a stylish and sporting touch, it’s to accommodate its tall, vertically fixed, six-cylinder engines. The block was designed to fit a large saloon after all.

38. As safety has always been a Mercedes-Benz totem – really coming to the fore in the 1950s and 1960s – provision for three-point safety belts were added in March 1966. A full 23 years before wearing seatbelts in the front seats became law in the UK.

39. According to its own literature, Mercedes-Benz heralded the W113 as the ‘first sports car worldwide with a safety body consisting of a rigid passenger cell and front and rear crumple zones.’ Such features had been pioneered by M-B with its W111 ‘Fintail’ saloon.

40. During its development, the W113’s engineers had something of a tall order. The new car was designed to replace both the 190SL and 300SL roadsters at the same time. A challenge few at the time would have envied. Though in reality, it wasn’t quite as clear cut. The W113 was more of an upgraded 190SL, without the motorsport considerations of the 300SL.

41. Prior to the Pagoda, sports cars were distinguished by being low, loud and hard to live with. In fact, many struggled to believe that the W113 was a true sports car, because it was just so well equipped, built and easy to live with. In short, it was a revelation and came to characterise the SL’s nature right up to the present.

42. Large sections of the W113 were made from aluminium, rather than steel. Door frames were cast in the lightweight material and the outer skins of the bonnet, doors and boot lid were also alloy. Despite this, the Pagoda still weighed nearly 1400kg, 200kgs or more above that of a contemporary Jaguar E-type or Porsche 911.

43. Despite often placing high among ‘greatest looking cars of all time’ polls, the press didn’t rave about the W113’s styling when it was launched. Road testers instead tended to marvel at the car’s technical advancements, plus its near ideal compromise of ride and handling.

44. Few would have thought of improving on the styling of the Pagoda, but Pininfarina was allowed to try in 1963. Then junior designer Tom Tjaarda made a handsome fixed-head coupe version of the 230SL by shortening the bonnet and increasing the rake of the grille, while also nipping on a sloping rear end. The result was a lot like another of Tjaarda’s 1960s creations, the Ferrari 330 GT 2+2 – hardly a bad comparison.

45. There was also a ‘shooting brake’ or estate 230SL for us Europeans, created by Turin coachbuilder Pietro Frua. The 230 SLX was an awkward one-off that, thankfully, went nowhere. Imagine a stretched SL that someone’s slapped an S-Class grille on, bleurgh!

46. Attractive tall or ‘stacked’ lichteinheits (headlamps to you and me) are a trait common to several Mercedes-Benz models from the 1960s including; 230, 250 and 280SLs, Fintail S-Class saloons and the 600 ‘Grosser’.

47. Its crisp and modern styling set the new SL apart from its more curvaceous predecessors, but it wasn’t the most aerodynamic shape. The W113 bludgeoned the air rather than slipped through it, with a frontal area similar to that of a garden shed at 0.51cd.

48. The Pagoda looked as good with its top down as it did with it up – as it did with its moniker inspiring hard top fitted too. Its easily erected and dropped soft top – itself a minor revelation – was stowed under a neat metal cover when not in use, keeping those lines neat.

49. If any further proof were needed of the Pagoda’s timeless appeal, it’s often been subjected to the resto mod treatment – especially in its native Germany. Mechatronik and Everrati has both recently taken Pagodas and updated their internals – while thankfully leaving the exterior largely un-altered. The former dropped in a ’90s Mercedes-Benz M113 4.3-litre V8 (somewhat fittingly), while the latter firm went all high-tech and electric. Though neither will give you much change from £300k…

50. The Pagoda comes from that glorious era when cars came in a myriad of shades, not just shades of grey like today. Possibly the most eye-catching and certainly one of the rarest is Copper Metallic (code 463H). It’s thought that this hardly seen colour was a special order, which explains its scarcity.

51. Subsequent SLs, after the 230, might not have looked too different from the first W113 but there were a number of changes under the skin. One telling alteration was the fitting of a new 82-litre fuel tank (up from 65) in the 250SL. Telling, because it showed how useable the new SL was and how longer journeys were easily achievable.

52. Many expect a larger differential in power between the entry-level 230SL and the final 280SL. There’s only a 20% boost in torque and 20bhp between the two models. The 230SL’s engine shines at higher rpm, something that many early owners didn’t fully appreciate. The idea of revving any engine regularly to 6500rpm in the early 1960s was thought damaging. Successive W113s upped the torque and displacement, bringing the power band lower down the rpm range.

53. The ‘golden era’ for Mercedes-Benz is often quoted as ranging from the mid-1950s to the mid-1990s. Within this era, engineering excellence was at the forefront of all M-B products and the W113 was certainly counted among them. The longevity of the Pagoda’s M127 straight-six is well known, but even so, rumours of an original owner in Germany having covered an astonishing 1 million kilometres (621,371 miles) without an engine rebuild, still comes as a surprise.

54. In the era of social media, with Instagram particularly the preserve of the fashionable, the Pagoda has seen something of a resurgence of interest. Younger owners might be barred by the high entry price, but nevertheless, seeing the model more online keeps it in the public consciousness. The W113 has always been popular with certain professionals, but once it reached classic status a few decades ago, many more photographers, artists and architects bought one.

55. Driving a 230SL and a 280SL back-to-back, you’ll likely notice a few differences between them. Other than the lower torque and power in the earlier model, this is made up for by a tighter handling chassis. That’s down to the longer service life rubber suspension items added to the 280SL, which some commentators at the time – namely the great L. J. K. Setright – felt made the 280SL handle less precisely than its grease-point equipped 230SL predecessor.

56. Shortly before the introduction of the W113, a competing model was in the works. By 1957, the idea of developing a six-cylinder powered 190SL gained an official production code (W127). Mercedes-Benz engineers had long known that the out-going 190SL was lacking in motive power, so the fitting of the Ponton’s 2195cc engine from the 220 (W180) made a lot of sense. Thankfully for us, the more aspirational idea of a whole new model based on the new Fintail saloon, won out.

57. Even by the mid-1960s, Mercedes-Benz was a dominant global automotive player. For example, it manufactured 174,007 passenger cars (including the Pagoda) and 66,331 commercial vehicles in 1965. Approximately 46% of this production went to the 160 countries M-B exported to. That netted the firm an astonishing DM4,470 million.

58. The introduction of the 280SL in 1967 meant Mercedes-Benz – and the rest of the world’s passenger car makers – had to comply with 17 new safety regulations. The late 1960s saw an increased, and many would say overdue, consideration for passenger safety. Luckily for M-B, its work in the 1950s on passive safety kept it well ahead of the curve.

59. The mechanical injection system used in the W113 was amazingly advanced for its time. Fuel injected passenger car engines were by no means common place in the early 1960s, yet the SL’s system could adjust automatically for atmospheric conditions and used coolant temperature monitoring to meter fuel more efficiently.

60. A 230SL, entered by touring car driver Dieter Glemser in the 1965 Acropolis Rally, finished a credible third place. He would have won outright were it not for some erroneous directions from a local police officer.

W113 COLOUR CHART AVAILABLE NOW

Share With Your Fellow Enthusiasts

Six decades ago, one of the most elegant, and dare we say iconic, open-top machines ever made was revealed at the prestigious Geneva Salon. The Pagoda SL arrived amid some of the most beautiful machinery ever to grace our roads – including the Jaguar E-type and Porsche 911. It nevertheless managed to trade blows with formidable foes and today has evolved into one of the most timelessly elegant and collectible classic cars in existence.

To celebrate its legacy, and continued popularity, we’ve amassed 60 top facts that sum up the W113, the SL generation that arguably more than any other, managed to distil the essence of this renowned open-top Mercedes-Benz.

TOP 60 MERCEDES PAGODA FACTS

1. In the 1960s, the average car owner – especially in Europe – was considered lucky if their machine came with a passenger side wing mirror or a radio. The W113 was an expensive car for sure, but even factoring this in, it was astonishingly well equipped. An automatic transmission and power steering might have been optional (though almost everyone ticked the boxes) but its fuel-injected, seven bearing (from 1966 in the 250 and 280) engines weren’t.

2. The single pivot rear end, the staple of previous Mercedes-Benz offerings, was reused for the W113, but not without trying to address some of its short comings. Under extreme conditions, the rear could jack up, leading to a sudden break in traction. The short-term solution M-B engineers settled upon was to develop a brand-new radial-ply tyre – in conjunction with tyre firms Continental and Firestone. The new tyre offered increased grip from a stiffer side wall, as per a radial, while maintaining much of the predictable breakaway of a cross ply.

3. Disc brakes all round were added for the larger engine 250 and 280 SLs. The 230 made do – perfectly well – with a disc and drum combo.

4. The Pagoda was the first SL to be developed by engineers who didn’t have to consider motorsport. The 1955 Le Mans disaster had shaken Mercedes-Benz, with its subsequent withdrawal from all factory-backed competition meaning there was no need to factor racing into the W113’s DNA.

5. One of the leading lights in passive safety at Stuttgart was M-B engineer Béla Barényi. Up to 1951, cars were still made outwardly as strong as possible, as it was thought safer for passengers. Barényi turned this idea on its head, making deformable outer sections of bodywork around a solid passenger safety cell – in other words, inventing the crumple zone.

6. Although circuit racing was out, Mercedes-Benz did continue to back select rally competitors. One of which was M-B works driver Eugen Böhringer. Deciding that the new more compact SL would be the ideal candidate for the gruelling Spa-Sofia-Liège event, Böhringer managed to convince M-B competitions manager Karl Kling to provide a suitably modified 230SL. This near standard 230SL managed to win the event against stiff competition from BMC’s Austin-Healey 3000, silencing critics of the new ‘softer’ SL in the process.

7. The Mercedes-Benz staple of increasing safety through mechanical innovation had taken giant leaps forward during the 1950s and much of what had been learned through crash-testing was implemented for the W113. The 280SL’s padded steering wheel centre and dashboard top merely the most obvious nods to passenger safety. There would also be head rests (on US models) and anchors for three-point safety belts.

8. The Pagoda design team was led by Friedrich Geiger, yet it’s thought likely designer Paul Bracq and engineer Béla Barényi also contributed heavily to the signed-off silhouette. Yet, as is so often the case with a design-house creation, the precise penmanship that lead to the final showroom appearance of the W113 is up for debate.

9. Few machines can boast as many glamorous alumni as the Pagoda SL. Songwriters John Lennon and Tina Turner both had one, alongside the ‘King’s’ widow, Priscilla Presley. More contemporary celebrity owners include F1 driver David Coulthard, former Spice Girl Emma Bunton and Harry Styles.

10. Despite their day job – or rather because of it – racing drivers also chose to ensconce themselves in the quiet style of this SL. All-time greats Juan Manual Fangio and arch rival Sir Stirling Moss are both counted among former owners.

11. Having spent four years in development, the W113 was unveiled to the world at the Geneva Salon in March of 1963. Two years earlier, the same event had seen the debut of another automotive icon of the era, the Jaguar E-type and the seminal Porsche 911 would be seen just 12 months later.

12. One of the few curves found on the straight-edged W113 was responsible for its popular nickname. The near unique concave bow of the hard-top roof – designed by engineer Béla Barényi to add strength, improve visibility and aid access – led many to compare it to the similarly-shaped roofs of ancient Asian buildings – after that, the name Pagoda stuck.

13. Suitably impressed with its new 6.3-litre V8 engine – developed for the magnificent 600 ‘Grosser’ saloon – the manager of the M-B experimental department Erich Waxenberger, had one fitted to a contemporary S-Class. The result was the astonishing 300SEL 6.3, but what’s less known, is that the same engine was fitted to a Pagoda. The resulting 250bhp, 140mph SL was good for a Nürburgring Nordschleife lap time of 10 mins 30 seconds.

14. In its eight-year production run, the W113 sold 48,912 units – the mass majority of which were 280 SLs.

15. A whopping 77 per cent of all Pagodas sold were specified with the optional four-speed automatic transmission. A figure that heavily implied who SL customers were and what they wanted from their open-top Mercedes-Benz experience. Information that Stuttgart would take into developing the W113’s replacement – the R107 – which was rarely offered with a manual.

16. In 1967, Mercedes-Benz showcased a Pagoda 2+2 coupe – unofficially known as the ‘California Coupe’ – at that year’s Geneva Motor Show. The space liberated by losing the soft-top roof was occupied by a pair of small rear seats.

17. During one of the W113’s press launches, at the compact 0.7-mile Montroux circuit, M-B legend and motorsport engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut – demonstrating the car, despite being 57-years old – managed a lap of 47.5 seconds. Also testing on the circuit that same day was Ferrari test engineer and future F1 racer Mike Parkes. Parkes managed to get his Ferrari 250GT Berlinetta around the same track, on the same day, in 47.3 seconds – just 0.2 seconds faster than Uhlenhaut in his far less powerful 230SL.

18. The 230SL was the first Mercedes-Benz road car to be fitted with disc brakes, but they weren’t German, they came from Britain. Girling’s disc brake system was used – together with a Master-Vac servo to power its front discs.

19. In 1968, another experimental engine was fitted to a Pagoda, this time a 203bhp Wankel. The test mule, designated W33-29, was tested for nearly 70,000km before the project was scrapped.

20. At launch, and for a long time during its production, some SL fans complained that the W113 had ‘gone soft’. A real sportscar with power steering was deemed a contradiction. Missing the point entirely that the powered recirculating ball system was actually quicker by half a turn than its manual alternative.

21. When the 250SL was introduced in 1967 it came with the new seven bearing engine from the 250SE saloon. Its piston area was no greater than that of the 230’s, the extra displacement coming from an increase in stroke. This lowered the engine’s powerband when compared to the peakier 230SL’s. Some loved its more accessible grunt (10% more torque), while others missed the high-revving nature of its smaller-displacement sibling.

22. The four-speed automatic transmission fitted to the W113 was well ahead of its time when it came to driver interaction. Fully automatic mode was achieved by slotting the lever into ‘4’. Dropping it down to ‘3’ locked out top gear, allowing the engine to rev out in third. The same was true of ‘2’, but it also forced first gear take offs – in any other position, the car took off in second.

23. Sir Stirling Moss, no stranger to Daimler-Benz of course, had his own 230SL converted with the bigger M129 engine from the 250SE. The former Mille Miglia winner loved his SL but, somewhat unsurprisingly, lusted after more power. He went to great pains to have his W113 converted privately, just before the factory did the job for him when it released the 250SL in 1967.

24. The Pagoda was the first mass-produced SL to be entirely powered by six-cylinder engines. There wouldn’t be another four-cylinder ‘SL’ until the SLK230, some three decades later, but at least it was supercharged.

25. Interestingly, 230SL and 280SL drivers were clearly very different. Made clear by the figures, three-quarters of 230SL buyers chose the manual transmission, while a staggering 90 per cent of the 280SL’s first owners went for the optional automatic.

26. The Pagoda was a technical and styling masterpiece but it certainly didn’t come cheap. The cost of a 280SL with power steering and automatic transmission options (as most came) in 1969, was nearly £4500. That was twice the cost of a 4.2-litre Jaguar E-type and equivalent to nearly £80k today.

27.

This generation of SL came in four distinct body styles. There was the Roadster, Coupe, Coupe 2/2 and Coupe Convertible. Essentially, all had a soft-top roof, except for the 2/2 that replaced the whole mechanism with a pair of rear seats. There was also the option of a rear ‘jump seat’ for a solitary transverse rear passenger, just to confuse matters.

28. Federal spec Pagodas differ a surprising amount from their European cousins. The separate sealed beam headlights are totally different, as are the milder camshafts and rubber-tipped over-riders. SLs destined for the United States also carried side wing reflectors, hazard lights and seat head rests. Rear axles had a lower ratio too. While some of these alterations are easily reversed, many aren’t. Converting to right-hand drive, for example, is perilously expensive and complicated.

29. In September 1964, the vertical spare wheel well was removed from the boot, with the spare tyre now stowed horizontal – significantly reducing luggage space in the process.

30. The 250SL is the rarest model of the three W113s. A total of 19,831 230SLs were built from 1963 to January 1967. The stop-gap 250SL was only made for one year (1967) with just 5196 made. The 280SL was the most numerous, with 23,885 built between December 1967 and the end of W113 production in March 1971.

31. Of the near 49,000 W113s made, almost half that number were sold to customers in the United States.

32. The wheelbase of the W113 is identical to its 190SL and 300SL predecessors at 2400mm.

33. Although the basic engine block used in all the W113s was the same as the W111 saloon’s, the more sporting application in the SL lead to a number of revisions. The most notable was the six-plunger injection pump – as opposed to the two plungers of the W111. This allowed more direct injection of fuel into the pre-heated (by surrounding coolant) intake ports, just ahead of the valves and cylinder – greatly increasing power.

34. Despite its engine developing 10 percent more torque and an increased displacement – from its lengthened stoke – the power the 250SL engine developed was essentially the same as its predecessor at 150bhp. The 250SL also had a slightly slower top speed than the 230, due to its increased weight – largely down to the new quad disc brakes and rear-axle compensator.

35. In typically understated fashion, the only distinguishing detail of the range-topping 280SL, apart from its rear model badges, were its new hubcaps.

36. The five-speed manual S5-20 transmission that was added from May 1966 – as an optional alternative to the default four-speed – was manufactured by Zahnradfabrik Friedrichshafen, better known as ZF. Just 882 customers opted for this five-speed box, making it an extremely rare and desirable factory option today.

37. The slight bulge in the bonnet of the W113 isn’t just a stylish and sporting touch, it’s to accommodate its tall, vertically fixed, six-cylinder engines. The block was designed to fit a large saloon after all.

38. As safety has always been a Mercedes-Benz totem – really coming to the fore in the 1950s and 1960s – provision for three-point safety belts were added in March 1966. A full 23 years before wearing seatbelts in the front seats became law in the UK.

39. According to its own literature, Mercedes-Benz heralded the W113 as the ‘first sports car worldwide with a safety body consisting of a rigid passenger cell and front and rear crumple zones.’ Such features had been pioneered by M-B with its W111 ‘Fintail’ saloon.

40. During its development, the W113’s engineers had something of a tall order. The new car was designed to replace both the 190SL and 300SL roadsters at the same time. A challenge few at the time would have envied. Though in reality, it wasn’t quite as clear cut. The W113 was more of an upgraded 190SL, without the motorsport considerations of the 300SL.

41. Prior to the Pagoda, sports cars were distinguished by being low, loud and hard to live with. In fact, many struggled to believe that the W113 was a true sports car, because it was just so well equipped, built and easy to live with. In short, it was a revelation and came to characterise the SL’s nature right up to the present.

42. Large sections of the W113 were made from aluminium, rather than steel. Door frames were cast in the lightweight material and the outer skins of the bonnet, doors and boot lid were also alloy. Despite this, the Pagoda still weighed nearly 1400kg, 200kgs or more above that of a contemporary Jaguar E-type or Porsche 911.

43. Despite often placing high among ‘greatest looking cars of all time’ polls, the press didn’t rave about the W113’s styling when it was launched. Road testers instead tended to marvel at the car’s technical advancements, plus its near ideal compromise of ride and handling.

44. Few would have thought of improving on the styling of the Pagoda, but Pininfarina was allowed to try in 1963. Then junior designer Tom Tjaarda made a handsome fixed-head coupe version of the 230SL by shortening the bonnet and increasing the rake of the grille, while also nipping on a sloping rear end. The result was a lot like another of Tjaarda’s 1960s creations, the Ferrari 330 GT 2+2 – hardly a bad comparison.

45. There was also a ‘shooting brake’ or estate 230SL for us Europeans, created by Turin coachbuilder Pietro Frua. The 230 SLX was an awkward one-off that, thankfully, went nowhere. Imagine a stretched SL that someone’s slapped an S-Class grille on, bleurgh!

46. Attractive tall or ‘stacked’ lichteinheits (headlamps to you and me) are a trait common to several Mercedes-Benz models from the 1960s including; 230, 250 and 280SLs, Fintail S-Class saloons and the 600 ‘Grosser’.

47. Its crisp and modern styling set the new SL apart from its more curvaceous predecessors, but it wasn’t the most aerodynamic shape. The W113 bludgeoned the air rather than slipped through it, with a frontal area similar to that of a garden shed at 0.51cd.

48. The Pagoda looked as good with its top down as it did with it up – as it did with its moniker inspiring hard top fitted too. Its easily erected and dropped soft top – itself a minor revelation – was stowed under a neat metal cover when not in use, keeping those lines neat.

49. If any further proof were needed of the Pagoda’s timeless appeal, it’s often been subjected to the resto mod treatment – especially in its native Germany. Mechatronik and Everrati has both recently taken Pagodas and updated their internals – while thankfully leaving the exterior largely un-altered. The former dropped in a ’90s Mercedes-Benz M113 4.3-litre V8 (somewhat fittingly), while the latter firm went all high-tech and electric. Though neither will give you much change from £300k…

50. The Pagoda comes from that glorious era when cars came in a myriad of shades, not just shades of grey like today. Possibly the most eye-catching and certainly one of the rarest is Copper Metallic (code 463H). It’s thought that this hardly seen colour was a special order, which explains its scarcity.

51. Subsequent SLs, after the 230, might not have looked too different from the first W113 but there were a number of changes under the skin. One telling alteration was the fitting of a new 82-litre fuel tank (up from 65) in the 250SL. Telling, because it showed how useable the new SL was and how longer journeys were easily achievable.

52. Many expect a larger differential in power between the entry-level 230SL and the final 280SL. There’s only a 20% boost in torque and 20bhp between the two models. The 230SL’s engine shines at higher rpm, something that many early owners didn’t fully appreciate. The idea of revving any engine regularly to 6500rpm in the early 1960s was thought damaging. Successive W113s upped the torque and displacement, bringing the power band lower down the rpm range.

53. The ‘golden era’ for Mercedes-Benz is often quoted as ranging from the mid-1950s to the mid-1990s. Within this era, engineering excellence was at the forefront of all M-B products and the W113 was certainly counted among them. The longevity of the Pagoda’s M127 straight-six is well known, but even so, rumours of an original owner in Germany having covered an astonishing 1 million kilometres (621,371 miles) without an engine rebuild, still comes as a surprise.

54. In the era of social media, with Instagram particularly the preserve of the fashionable, the Pagoda has seen something of a resurgence of interest. Younger owners might be barred by the high entry price, but nevertheless, seeing the model more online keeps it in the public consciousness. The W113 has always been popular with certain professionals, but once it reached classic status a few decades ago, many more photographers, artists and architects bought one.

55. Driving a 230SL and a 280SL back-to-back, you’ll likely notice a few differences between them. Other than the lower torque and power in the earlier model, this is made up for by a tighter handling chassis. That’s down to the longer service life rubber suspension items added to the 280SL, which some commentators at the time – namely the great L. J. K. Setright – felt made the 280SL handle less precisely than its grease-point equipped 230SL predecessor.

56. Shortly before the introduction of the W113, a competing model was in the works. By 1957, the idea of developing a six-cylinder powered 190SL gained an official production code (W127). Mercedes-Benz engineers had long known that the out-going 190SL was lacking in motive power, so the fitting of the Ponton’s 2195cc engine from the 220 (W180) made a lot of sense. Thankfully for us, the more aspirational idea of a whole new model based on the new Fintail saloon, won out.

57. Even by the mid-1960s, Mercedes-Benz was a dominant global automotive player. For example, it manufactured 174,007 passenger cars (including the Pagoda) and 66,331 commercial vehicles in 1965. Approximately 46% of this production went to the 160 countries M-B exported to. That netted the firm an astonishing DM4,470 million.

58. The introduction of the 280SL in 1967 meant Mercedes-Benz – and the rest of the world’s passenger car makers – had to comply with 17 new safety regulations. The late 1960s saw an increased, and many would say overdue, consideration for passenger safety. Luckily for M-B, its work in the 1950s on passive safety kept it well ahead of the curve.

59. The mechanical injection system used in the W113 was amazingly advanced for its time. Fuel injected passenger car engines were by no means common place in the early 1960s, yet the SL’s system could adjust automatically for atmospheric conditions and used coolant temperature monitoring to meter fuel more efficiently.

60. A 230SL, entered by touring car driver Dieter Glemser in the 1965 Acropolis Rally, finished a credible third place. He would have won outright were it not for some erroneous directions from a local police officer.

W113 COLOUR CHART AVAILABLE NOW

Share With Your Fellow Enthusiasts

More from Journal

CARE

THE ULTIMATE CERTIFIED SERVICING INVESTMENT PLAN

Your ownership journey matters to us, which is why we have created a simple certified servicing investment plan, tailored to your individual needs and aspirations.

Start investing today and our dedicated CARE team will work with you to increase the value and enjoyment you receive from your vehicle.

STAY IN TUNE WITH SLSHOP MOMENTS

As part of SLSHOP’s community of enthusiasts, you’ll be the first to hear about events and tours, key product offers, exciting stories from owners around the world and of course… our latest additions to the showroom. So, be the first to know and you might just sneak a car on your driveway or take your car’s condition to new heights with our exclusive replacement parts.

Or, visit SLSHOP Journal