Thursday 12th August, 2021

Happy birthday to the iconic Mercedes Convertible!

Fifty years ago, Mercedes unveiled what would become the longest running and best-selling SL generation. To mark the anniversary, Martin Buckley visited SLSHOP in Warwickshire to describe and drive early and late examples of Stuttgart’s much loved roadster.

The Iconic Mercedes Convertible – 50 Years On

Even now, more than three decades after the last examples were built, the 107-series is the car anyone over 50 conjures up in his or her mind’s eye when the subject of Mercedes SLs is raised. No subsequent Mercedes roadster has got anywhere near matching its 18 years and four months production run, or its visibility as the aspirational flagship of the German marque.

In a life cycle that spanned the remnants of flower power to the new romantics and beyond, it saw out two generations of S-Classes and is only out lived by the G-Class SUV. Here was a ‘lifestyle’ luxury automobile that resonated even with those who had no more than a passing interest in motorcars; the luxury roadster everyone’s mum dreamed of, and quite a few dads too.

Always reassuringly expensive, the R107 – the first V8 engined SL – became a timeless default statement of affluence, its reputation peaking somewhere in the early 1980s and underpinned in the public consciousness by appearances in American TV shows such as Dallas and Hart to Hart.

Although well proportioned, it will not, perhaps, be remembered as the best looking of the SL family. But not even fussy quad headlamps and ‘park bench’ federal impact bumpers for the North American market (where over two-thirds of R107s were sold) could hurt its Teflon-coated image as an object of desire in the 1970s and 80s.

Those were very different times. Today’s status car landscape is a much more noisy and lurid one, where a greater willingness to flaunt wealth is combined with an access to credit that was unheard of 50 years ago.

The R107 was the product of a time when the very wealthy were fewer in number and had a much narrower choice of true status symbol motorcars to choose from. If you factored in the SL’s practicality and open-topped appeal, it stood almost unchallenged a time when the high first cost of a Mercedes convertible was widely understood to be entirely justified not only by the excellence and durability of the car itself but also by its almost unique ability to hold its value in a seller’s market that would take as many cars as Untertürkheim could build.

In that market, SL ownership seemed a better bet than money in the bank, doubtless assisted by the fact that the shape didn’t change between 1971 and 1989. Only different styles of alloy wheel, spoilers, door handles, dashboard trim and badges visually separated the first of the 350SLs from the last of the 500SLs and 560SLs.

The Design Path of the R107 SL

The preceding W113 Pagoda wasn’t a ‘pure’ sports car, but it had established the concept of a luxury Mercedes convertible two-seater with sporty overtures plus strong feminine appeal combined with the elegant practicality of its famously dished hardtop. This signature headgear linked the shape of the R107 with its predecessor but there were few other visual clues.

Gently wedge-shaped in profile, with distinctive corrugated flanks, the new SL had its origins in the mid-1960s. With this car, Daimler-Benz addressed the crash safety challenges of the next decade with an SL that looked as strong as it actually was. Certain details, like the wrap-around, ribbed self-cleaning indicators, predicted the look of future saloon models to give a family identity.

That the internal nickname for the R107 in Stuttgart was Der Panzerwagen was appropriate. With its steering box behind the axle line and the fuel tank against the rear bulkhead (rather than under the boot floor) it was as safe as modern technology could make an open topped car in 1971, and probably as well heated and ventilated as any other vehicle of its type in the world.

Buyers could have electric windows and air conditioning, but they had to raise and lower the soft top manually and be prepared to find a hoe for the strong but heft optional hardtop when spring arrived. Such versatility was hard to find elsewhere although British Leyland’s three-litre V8-engined Triumph Stag came surprisingly close, and at a third of the SL’s £6,000 price tag when right-hand drive examples arrived in the UK.

In the same way that the WS113 SL had taken its technical lead from the six-cylinder, low pivot swing-axle equipped Benz saloons of the late 1950s and 60s, the R107 was a sister car to the still unannounced 116-series S-Class, combining the latest M116 3.5-litre fuel-injected V8 with a three-speed automatic gearbox, a fully overridable type with a fluid coupling rather than torque convertor. Mercedes had long since lost interest in selling large engine cars with its synchromesh gearbox but a few four-speed manual 350s were sold; coincidentally the first R107 SL I ever drove was a manual transmission 350SL.

If you insisted on stirring your own gears, Mercedes would direct you to the 280SL from 1974 which came as standard with a manual ‘box and even five speeds from 1980. In combination with the high revving, straight-six 2.7-litre twin-cam M110 engine, this was about as overtly sporty as the dignified R107 ever got. If the manual gearbox was not quite consigned to history on the R107, the famous Stuttgart swing-axles were, replaced with the semi-trailing arms of the W114/W115 at the rear, and new anti-dive technology at the front for the double wishbones and coils.

The design of the R107’s chassis largely answered those quietly whispered misgivings about the ultimate behaviour of the previous generation of SLs. Although the 350SLs suffered from squat under hard acceleration (cured on the 450SL) these 1970s SLs were thankfully not subject to the lift off oversteer that could make a Pagoda a tricky machine to drive in certain situations.

Marginally longer, lower and rather heavier than the W113 the 350SL, launched to the press at the Hockenheim circuit, was also a much more crashworthy one with roof pillars that were 50 per cent stronger. On Bosch electronic injection which gave 197bhp, the 350 still managed a slightly more favourable power weight ratio than the 180kg lighter outgoing 280SL offering 168bhp.

Powertrain of the R107 SL Mercedes Convertible

Between 1971 and 1989 no less than six varieties of the fuel-injected, overhead camshaft V8 would be offered in the R107 body as Daimler-Benz sought to keep the SL up to date on output and emissions.

The 450SL was devised as a way of winning back the performance lost to emissions equipment on first US-bound cars (which were badged 350SL despite the 4.5 litres). From 1973 until 1980 in European form, the 450SL gave first 222bhp, lowered to 212bhp in late 1975, but the only way of differentiating a 280SL from a 450SL (other than the bootlid badge) were the skinnier tyres of the former and the discreet chin spoiler of the latter.

A much smoother form of three-speed automatic with a torque converter was introduced in 1975. Four-wheel disc brakes with duplicated circuits were a given, although the anti-lock braking system talked of in 1971 did not become standard until the SL’s final revamp in autumn 1975.

In March 1980, the 350 and 450SL motors were usurped by new all-alloy V8s of 3.8 and five litres to become the 380SL and 500SL with 215 and 237bhp respectively and gained the latest four-speed automatic gearbox. In 1981, the SL’s engines benefitted from the ‘energy concept’ enhancements devised for the latest S-Class saloons, a combination of higher compression ratio and massaged exhaust tracts and combustion chambers.

In Autumn 1985, for the 1986 model year, improved inlet valves and new camshaft profiles teased 242bhp out of the 500, with enough torque, 289lb ft, to give its now standard fit limited-slip differential a workout. At the same time the 380SL became the bored out 420SL and the 280SL was replaced by the evocatively named 300SL powered by the latest canted over, single-overhead camshaft M103 straight-six first seen in the W124 300E. The 560SL was an export only model – North America, Japan and Australia – restricted to 227bhp by emissions equipment.

Over almost two decades the popularity of the R107 SL proved immune to both fuel crisis and financial slumps, probably because it appealed to the sorts of people who were insulated against such events. It presided over an era when Mercedes’ reputation for engineering excellence was at its zenith, when even a humble four-cylinder 240D saloon was a possession to be proud of, never mind a decadent two-seater that cost rather more than the houses most people lived in.

Since the R107 we’ve had the SLK as an entry-level Mercedes convertible sports car, but in 1971 the idea of diluting the glamour of the flagship SL would have been unthinkable. Neither was this generation of SL over produced in the way the subsequent R129 arguably was, although 237,287 cars is a healthy total for an exclusive convertible.

Sports car? The name flatters the R107 but also fails to do it justice. In many ways, it is a much cleverer device: a luxury vehicle first and foremost, that has most of the attributes but much fewer of the vices of a traditional open topped two-seater. Wrapped up in a safer, more opulent and more refined engineering package than ever, the SL for the 1970s did not look to take on the E-Types and 911s of its era but was perhaps best thought of as a kind of re-imagined and superior 1955 Ford Thunderbird; motoring escapism, but in the Teutonic idiom of uncompromised engineering superiority.

Driving the R107s

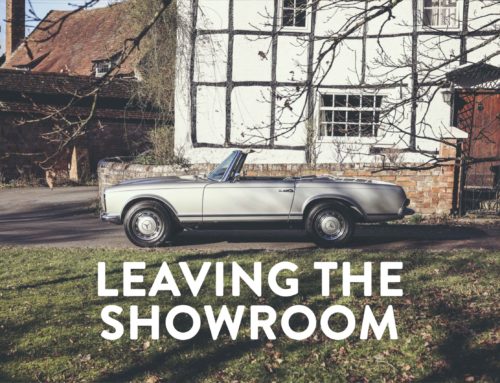

Thanks to Mercedes convertible specialist SLShop loaning us early and late examples, Martin Buckley was able to make a direct, on-the-road comparison of two R107s that look almost identical on the outside and very similar inside, but which feel different behind the wheel.

As a period piece, the 1974 Icon gold 350SL featured here is perhaps a better looking car than it seemed 10 or 15 years ago. It looks ‘classic’ whereas the 500SL could be accused of dressing too young with the spoilers and flag-focused alloys that were introduced in the mid-1980s. But while the purity and authenticity of the 350SL is good to see, it is almost entirely trumped by the way the younger car drives.

It’s not just a question of straight-line performance. I quite enjoy the austerity of SL Shop’s very tidy early car with its MB-Tex seats and unrelenting swathes of crash-safe injection mouldings, but the leather chairs of the firm’s 500 hold you in place more firmly and even a 70s purist would have to admit that its cabin is a friendlier environment.

Naturally, the five-litre SL is faster in raw figures, but it also feels much sharper than the relatively small gains in horsepower and torque would suggest: where the 350SL is almost leisurely when the throttle is floored, there is an urgency to the way the 500SL lunges away. You can light up the rear tyres and reel in the horizon effortlessly, while the older car still seems to be pondering over its gear changes: they slur through compared to the crisp, responsive feel of the 500’s shift with its eager kickdown.

Both cars have oversize steering wheels but there’s a vagueness around the straight ahead on the older car that robs it of the sort of driver appeal that might encourage press-on motoring. It is a brisk and pleasant machine to whisk through long gentle curves, but feels just a shade too soft on slower, tighter ones. Driven in such a manner, the 500SL is less obtrusive: the steering has more feel, there is less roll and the car turns in more faithfully, perhaps as a result of tweaks to geometry on these later 107s as Mercedes strove to maintain the ageing SL’s driver appeal against younger opposition from the likes of Porsche, Audi, BMW and all the others.

North America in mind

Production figures for the R107 show how important the US market was for the R107, where the starting point for exclusive motoring was a V8.

Of the nearly 237,300 R107 SLs manufactured, over 49,300 – 21 per cent – were of the 560SL, a model designed with North America in mind and not available to European buyers, writes David Sutherland. The number looks all the more telling given that this flagship was built for just four years of the R107’s 18-year run.

The highest selling model was the 1971 – 1980 450SL with 66,298 deliveries according to Daimler AG archive data, followed by the 1980-1985 380SL. By contrast, six-cylinder models were comparatively low sellers, the 280SL and 300SL between them accounting for 39,178 (17 per cent), but the least sought version was the 1985-1989 420SL, arguably a somewhat irrelevant halfway house between the 300SL and 500SL, with just 2,148 ordered.

But while wealthy Americans loved the R107, owners had to put up with a big performance deficit over European spec cars., with a steady decline in power output due to ever tightening emission controls. The 450SL began with 222bhp/27lb ft torque, but by 1973 had dropped to 187bhp/240lb ft, a specification extended to all US other states in 1975. By the time the 450SL gave way to the 500SL, in 1980, it was mustering a mere 158bhp/230lb ft, 15 per cent less horsepower than the European 280SL. Although the 560SL of 1986 sought to address this matter, its 227bhp/274ib ft was still below the European 500SL’s output.

Oh Lord Won’t You Buy Me a Convertible Mercedes? Discover SLSHOP’s current showroom inventory.

Share With Your Fellow Enthusiasts

Thursday 12th August, 2021

Happy birthday to the iconic Mercedes Convertible!

Fifty years ago, Mercedes unveiled what would become the longest running and best-selling SL generation. To mark the anniversary, Martin Buckley visited SLSHOP in Warwickshire to describe and drive early and late examples of Stuttgart’s much loved roadster.

The Iconic Mercedes Convertible – 50 Years On

Even now, more than three decades after the last examples were built, the 107-series is the car anyone over 50 conjures up in his or her mind’s eye when the subject of Mercedes SLs is raised. No subsequent Mercedes roadster has got anywhere near matching its 18 years and four months production run, or its visibility as the aspirational flagship of the German marque.

In a life cycle that spanned the remnants of flower power to the new romantics and beyond, it saw out two generations of S-Classes and is only out lived by the G-Class SUV. Here was a ‘lifestyle’ luxury automobile that resonated even with those who had no more than a passing interest in motorcars; the luxury roadster everyone’s mum dreamed of, and quite a few dads too.

Always reassuringly expensive, the R107 – the first V8 engined SL – became a timeless default statement of affluence, its reputation peaking somewhere in the early 1980s and underpinned in the public consciousness by appearances in American TV shows such as Dallas and Hart to Hart.

Although well proportioned, it will not, perhaps, be remembered as the best looking of the SL family. But not even fussy quad headlamps and ‘park bench’ federal impact bumpers for the North American market (where over two-thirds of R107s were sold) could hurt its Teflon-coated image as an object of desire in the 1970s and 80s.

Those were very different times. Today’s status car landscape is a much more noisy and lurid one, where a greater willingness to flaunt wealth is combined with an access to credit that was unheard of 50 years ago.

The R107 was the product of a time when the very wealthy were fewer in number and had a much narrower choice of true status symbol motorcars to choose from. If you factored in the SL’s practicality and open-topped appeal, it stood almost unchallenged a time when the high first cost of a Mercedes convertible was widely understood to be entirely justified not only by the excellence and durability of the car itself but also by its almost unique ability to hold its value in a seller’s market that would take as many cars as Untertürkheim could build.

In that market, SL ownership seemed a better bet than money in the bank, doubtless assisted by the fact that the shape didn’t change between 1971 and 1989. Only different styles of alloy wheel, spoilers, door handles, dashboard trim and badges visually separated the first of the 350SLs from the last of the 500SLs and 560SLs.

The Design Path of the R107 SL

The preceding W113 Pagoda wasn’t a ‘pure’ sports car, but it had established the concept of a luxury Mercedes convertible two-seater with sporty overtures plus strong feminine appeal combined with the elegant practicality of its famously dished hardtop. This signature headgear linked the shape of the R107 with its predecessor but there were few other visual clues.

Gently wedge-shaped in profile, with distinctive corrugated flanks, the new SL had its origins in the mid-1960s. With this car, Daimler-Benz addressed the crash safety challenges of the next decade with an SL that looked as strong as it actually was. Certain details, like the wrap-around, ribbed self-cleaning indicators, predicted the look of future saloon models to give a family identity.

That the internal nickname for the R107 in Stuttgart was Der Panzerwagen was appropriate. With its steering box behind the axle line and the fuel tank against the rear bulkhead (rather than under the boot floor) it was as safe as modern technology could make an open topped car in 1971, and probably as well heated and ventilated as any other vehicle of its type in the world.

Buyers could have electric windows and air conditioning, but they had to raise and lower the soft top manually and be prepared to find a hoe for the strong but heft optional hardtop when spring arrived. Such versatility was hard to find elsewhere although British Leyland’s three-litre V8-engined Triumph Stag came surprisingly close, and at a third of the SL’s £6,000 price tag when right-hand drive examples arrived in the UK.

In the same way that the WS113 SL had taken its technical lead from the six-cylinder, low pivot swing-axle equipped Benz saloons of the late 1950s and 60s, the R107 was a sister car to the still unannounced 116-series S-Class, combining the latest M116 3.5-litre fuel-injected V8 with a three-speed automatic gearbox, a fully overridable type with a fluid coupling rather than torque convertor. Mercedes had long since lost interest in selling large engine cars with its synchromesh gearbox but a few four-speed manual 350s were sold; coincidentally the first R107 SL I ever drove was a manual transmission 350SL.

If you insisted on stirring your own gears, Mercedes would direct you to the 280SL from 1974 which came as standard with a manual ‘box and even five speeds from 1980. In combination with the high revving, straight-six 2.7-litre twin-cam M110 engine, this was about as overtly sporty as the dignified R107 ever got. If the manual gearbox was not quite consigned to history on the R107, the famous Stuttgart swing-axles were, replaced with the semi-trailing arms of the W114/W115 at the rear, and new anti-dive technology at the front for the double wishbones and coils.

The design of the R107’s chassis largely answered those quietly whispered misgivings about the ultimate behaviour of the previous generation of SLs. Although the 350SLs suffered from squat under hard acceleration (cured on the 450SL) these 1970s SLs were thankfully not subject to the lift off oversteer that could make a Pagoda a tricky machine to drive in certain situations.

Marginally longer, lower and rather heavier than the W113 the 350SL, launched to the press at the Hockenheim circuit, was also a much more crashworthy one with roof pillars that were 50 per cent stronger. On Bosch electronic injection which gave 197bhp, the 350 still managed a slightly more favourable power weight ratio than the 180kg lighter outgoing 280SL offering 168bhp.

Powertrain of the R107 SL Mercedes Convertible

Between 1971 and 1989 no less than six varieties of the fuel-injected, overhead camshaft V8 would be offered in the R107 body as Daimler-Benz sought to keep the SL up to date on output and emissions.

The 450SL was devised as a way of winning back the performance lost to emissions equipment on first US-bound cars (which were badged 350SL despite the 4.5 litres). From 1973 until 1980 in European form, the 450SL gave first 222bhp, lowered to 212bhp in late 1975, but the only way of differentiating a 280SL from a 450SL (other than the bootlid badge) were the skinnier tyres of the former and the discreet chin spoiler of the latter.

A much smoother form of three-speed automatic with a torque converter was introduced in 1975. Four-wheel disc brakes with duplicated circuits were a given, although the anti-lock braking system talked of in 1971 did not become standard until the SL’s final revamp in autumn 1975.

In March 1980, the 350 and 450SL motors were usurped by new all-alloy V8s of 3.8 and five litres to become the 380SL and 500SL with 215 and 237bhp respectively and gained the latest four-speed automatic gearbox. In 1981, the SL’s engines benefitted from the ‘energy concept’ enhancements devised for the latest S-Class saloons, a combination of higher compression ratio and massaged exhaust tracts and combustion chambers.

In Autumn 1985, for the 1986 model year, improved inlet valves and new camshaft profiles teased 242bhp out of the 500, with enough torque, 289lb ft, to give its now standard fit limited-slip differential a workout. At the same time the 380SL became the bored out 420SL and the 280SL was replaced by the evocatively named 300SL powered by the latest canted over, single-overhead camshaft M103 straight-six first seen in the W124 300E. The 560SL was an export only model – North America, Japan and Australia – restricted to 227bhp by emissions equipment.

Over almost two decades the popularity of the R107 SL proved immune to both fuel crisis and financial slumps, probably because it appealed to the sorts of people who were insulated against such events. It presided over an era when Mercedes’ reputation for engineering excellence was at its zenith, when even a humble four-cylinder 240D saloon was a possession to be proud of, never mind a decadent two-seater that cost rather more than the houses most people lived in.

Since the R107 we’ve had the SLK as an entry-level Mercedes convertible sports car, but in 1971 the idea of diluting the glamour of the flagship SL would have been unthinkable. Neither was this generation of SL over produced in the way the subsequent R129 arguably was, although 237,287 cars is a healthy total for an exclusive convertible.

Sports car? The name flatters the R107 but also fails to do it justice. In many ways, it is a much cleverer device: a luxury vehicle first and foremost, that has most of the attributes but much fewer of the vices of a traditional open topped two-seater. Wrapped up in a safer, more opulent and more refined engineering package than ever, the SL for the 1970s did not look to take on the E-Types and 911s of its era but was perhaps best thought of as a kind of re-imagined and superior 1955 Ford Thunderbird; motoring escapism, but in the Teutonic idiom of uncompromised engineering superiority.

Driving the R107s

Thanks to Mercedes convertible specialist SLShop loaning us early and late examples, Martin Buckley was able to make a direct, on-the-road comparison of two R107s that look almost identical on the outside and very similar inside, but which feel different behind the wheel.

As a period piece, the 1974 Icon gold 350SL featured here is perhaps a better looking car than it seemed 10 or 15 years ago. It looks ‘classic’ whereas the 500SL could be accused of dressing too young with the spoilers and flag-focused alloys that were introduced in the mid-1980s. But while the purity and authenticity of the 350SL is good to see, it is almost entirely trumped by the way the younger car drives.

It’s not just a question of straight-line performance. I quite enjoy the austerity of SL Shop’s very tidy early car with its MB-Tex seats and unrelenting swathes of crash-safe injection mouldings, but the leather chairs of the firm’s 500 hold you in place more firmly and even a 70s purist would have to admit that its cabin is a friendlier environment.

Naturally, the five-litre SL is faster in raw figures, but it also feels much sharper than the relatively small gains in horsepower and torque would suggest: where the 350SL is almost leisurely when the throttle is floored, there is an urgency to the way the 500SL lunges away. You can light up the rear tyres and reel in the horizon effortlessly, while the older car still seems to be pondering over its gear changes: they slur through compared to the crisp, responsive feel of the 500’s shift with its eager kickdown.

Both cars have oversize steering wheels but there’s a vagueness around the straight ahead on the older car that robs it of the sort of driver appeal that might encourage press-on motoring. It is a brisk and pleasant machine to whisk through long gentle curves, but feels just a shade too soft on slower, tighter ones. Driven in such a manner, the 500SL is less obtrusive: the steering has more feel, there is less roll and the car turns in more faithfully, perhaps as a result of tweaks to geometry on these later 107s as Mercedes strove to maintain the ageing SL’s driver appeal against younger opposition from the likes of Porsche, Audi, BMW and all the others.

North America in mind

Production figures for the R107 show how important the US market was for the R107, where the starting point for exclusive motoring was a V8.

Of the nearly 237,300 R107 SLs manufactured, over 49,300 – 21 per cent – were of the 560SL, a model designed with North America in mind and not available to European buyers, writes David Sutherland. The number looks all the more telling given that this flagship was built for just four years of the R107’s 18-year run.

The highest selling model was the 1971 – 1980 450SL with 66,298 deliveries according to Daimler AG archive data, followed by the 1980-1985 380SL. By contrast, six-cylinder models were comparatively low sellers, the 280SL and 300SL between them accounting for 39,178 (17 per cent), but the least sought version was the 1985-1989 420SL, arguably a somewhat irrelevant halfway house between the 300SL and 500SL, with just 2,148 ordered.

But while wealthy Americans loved the R107, owners had to put up with a big performance deficit over European spec cars., with a steady decline in power output due to ever tightening emission controls. The 450SL began with 222bhp/27lb ft torque, but by 1973 had dropped to 187bhp/240lb ft, a specification extended to all US other states in 1975. By the time the 450SL gave way to the 500SL, in 1980, it was mustering a mere 158bhp/230lb ft, 15 per cent less horsepower than the European 280SL. Although the 560SL of 1986 sought to address this matter, its 227bhp/274ib ft was still below the European 500SL’s output.

Oh Lord Won’t You Buy Me a Convertible Mercedes? Discover SLSHOP’s current showroom inventory.

Share With Your Fellow Enthusiasts

More from Journal

CARE

THE ULTIMATE CERTIFIED SERVICING INVESTMENT PLAN

Your ownership journey matters to us, which is why we have created a simple certified servicing investment plan, tailored to your individual needs and aspirations.

Start investing today and our dedicated CARE team will work with you to increase the value and enjoyment you receive from your vehicle.

STAY IN TUNE WITH SLSHOP MOMENTS

As part of SLSHOP’s community of enthusiasts, you’ll be the first to hear about events and tours, key product offers, exciting stories from owners around the world and of course… our latest additions to the showroom. So, be the first to know and you might just sneak a car on your driveway or take your car’s condition to new heights with our exclusive replacement parts.

Or, visit SLSHOP Journal