CLASSIC MERCEDES Issue 34 Spring 2021

Sports Star!

Bracq’s Mercedes Pagoda still a winner

Article written by Classic Mercedes Editor, David Sutherland

Editorial:

In this issue of Class Mercedes

… Still on convertibles, I’ve driven possibly the best Mercedes Pagoda I’ve ever come across, a late 280SL restored by SLShop. I hope my words on pages 20-26 convey not just how exquisite this particular car is to look at and drive, but how much of a game changer the W113 was when launched 58 years ago…

Cover Story:

Modern World

“ A major W113 innovation was the factory-supplied hardtop, a substantial and strong metal item that was beautifully engineered and styled as the car itself. ”

When launched in 1963 the Mercedes Pagoda (W113) roadster redefined the SL concept, the ultra-modern shape with tis 2.3-litre six-cylinder engine replacing both the 190SL and 300SL.

David Sutherland looks back at how it was received at the time, and drives a beautifully restored last-of-the-line 280SL.

Sensational as the original 300SL of 1954 and the Roadster version launched four years later had been, by the early 1960s Mercedes’ sports cars were no longer doing the whole job needed of them. In the fast modernisation early in that decade curvaceous, aero jet inspired styling was no longer on trend as straight lines and sharp angles became the accepted design cues, and the SL range was even looking ill defined, given that the 190SL and 300SL were very close in styling but a world apart in engineering. As the reporter for Road & Track magazine, Eberhard Seifert, noted in 1963: “The 190SL touring sports car and the high performance 300SL were becoming out of date both technically and in appearance. The last model of the 190SL, seen at the Brussels exhibition, seemed lonely and obsolete. “Some fresh thinking was needed to take the Sport Leicht concept forward – and the W113 series SL presented in March 1963 delivered the goods with flair and fashion.

The all new 230SL logically replaced both the 190SL and 300SL, its 2.3-litre six-cylinder engine making it a mid-point between the underpowered former and the superfast latter. Arguably the high career point of Mercedes-Benz stylist Paul Bracq, its sharp-waisted body with super slim pillars and a huge glass house made the Pagoda probably the freshest looking car in the world at the time (just as the Gullwing has been when unveiled nine years earlier). In the intervening 58 years, the Mercedes Pagoda has become possibly the most loved post-war Mercedes sports car shape, but at the time it was radical, even risky.

Driving the Mercedes Pagoda

Before it was despatched to a new owner in South Africa, David Sutherland took this immaculate 1970 280SL out on the road and enjoyed what he found.

In the nine years I have edited Classic Mercedes magazine, I have been fortunate enough to drive a wide selection of W113 SLs, and this has highlighted that while a Pagoda may look stunning, this is no promise that the quality of the drive matches the appearance. Some feel wonderful and make you long to drive all day, others are dogs you want to hand back as soon as possible.

Thankfully the example seen here is the former. But I knew it would be, because it was a nut and bolt restoration by Warwickshire-based SL Shop, which has considerable Pagoda experience, and which charges enough for its finished work for that to be guaranteed.

Located by SL Shop director Bruce Greetham for a bespoke rebuild for a South African customer, the 1970 280SL was turned up in a barn in Somerset. It had been bought as a wedding present but its sale 20 years later was part of a divorce settlement, by which time it had rusted and generally deteriorated to an unroadworthy condition. Importantly, though, it was a ‘matching numbers’ car (retaining the factory issued engine and chassis numbers), which the customer had insisted on, and was complete.

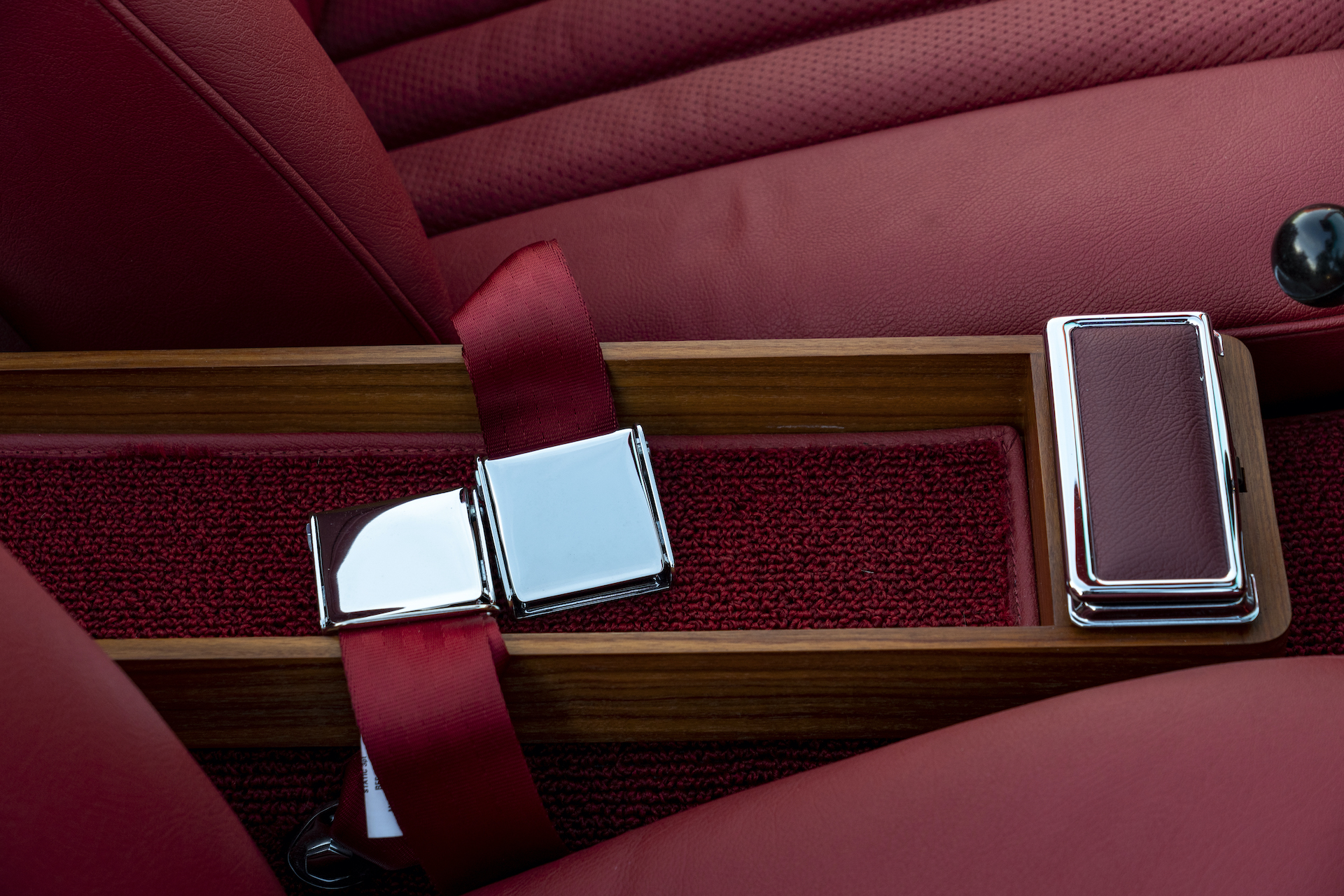

It had started life in DB180 Silver Grey, but following discussions with Bruch the customer settled on Anthracite Grey (DB172) with red leather. The contrast between the discreet body colour and extrovert interior makes for an intriguing combination, I feel.

The soft, near collapsed seats that have vainly attempted to support the Sutherland frame in many a Pagoda drive were thankfully absent, in their place pert bases and backrests that delivered the ideal height and firmness. The fresh, vivid redness of the seat, dash and steering wheel boss was so delicious I almost wanted to lick it, the same applying to the lovely milk chocolatey wood trim on the dash top and transmission funnel.

An added bonus was the presence of a period correct Becker Mexico four-band radio.

Pagoda engines, if running correctly, should be sharp, raspy and responsive, and this was that and more, although Bruce told me that the pronounced note from the exhaust would calm as the brand new system wore in.

The four speed automatic gearbox, with the odd Mercedes Pagoda gate of Drive three notches forward of Park, shifted quickly if not so smoothly and gave off a small amount of gear whine, but this is hardly an issue on a five-decade old car. The high point of this example’s dynamics was the handling: the springing and damping – often way out on Pagodas – was spot on, providing a delightfully settled ride and absorbing bumps beautifully. The steering, with power-assistance, was crisp and quiet.

Overall this rates as one of the best presented and set up Pagodas I’ve tried. But of course when you write out a cheque for well over £100,000 – Bruce isn’t saying what his customer, an SL Shop regular, paid – no less is expected!

“At first glance we found the upper lines of the compact body to be somewhat shocking,” Seifert wrote in his approval. “However on better acquaintance with this interesting car with all its fascinating detail we grew more and more enthusiastic.” The select group of customers able to afford the 230SL’s price – twice that of a basic Fintail – needed no convincing, the car soon generated a long waiting list for delivery.

With a relatively high production target in mind, the W113 had to be closer in configuration to the 190SL than the 300SL, thus much below the skin came from the Fintail. The Bosch fuel-injected, M127 overhead-camshaft engine was from the 220SE, power pushed up 20 bhp to 147bhp and produced 700rpm higher at 5,500rpm; torque was raised fractionally to 145lb ft. The gearbox was four-speed, manual or automatic. The suspension was also taken from the Fintail, coils and wishbones at the front and a swing-axle at the rear.

The 190SL, assuming the lower half of the Ponton’s monocoque construction, had already carved out a niche as a sports car with a high level of comfort and equipment compared to most other roadsters, which were extremely basic. Stuttgart intended to extend that aspect much further and appeal to customers who wanted an open two-seater than was comfortable as well as sporty. Hence if you compare a W113 to any MG of the time or even a Jaguar E-Type, it feels luxurious. The seats were larger and comfortably padded, and power-assisted steering was optionally available from the start.

A major W113 innovation was the factory-supplied hardtop, a substantial and strong metal item that was a beautifully engineered and styled as the car itself, and which would also be a feature on the subsequent R107 and R129 generations, the tradition ending when the 2002 R230SL arrived with its power-folding metal roof. It wasn’t long before the W113’s lid, with its concave top section designed for structural strength as well as to look pretty, brought the name ‘Pagoda’ (which the factory itself thought up) to this model series.

Safety, not previously associated with sports cars, was an important feature of the W113. Mercedes safety guru Béla Barényi was at the height of his powers and following his creation of the passenger safety cell in the Fintail, applied the same stiff body unit and energy absorbing crash deformation cells to an open car for the first time. Front disc brakes were fitted, still a rare feature on road cars in those days.

This was no bone-jarring, teeth-rattling almost solidly sprung sports car, as Road & Track concluded once it was able to spend more time with the 230SL. “Springing is very, very sort, with excellent damping, and on corners it feels as if the limit could never be reached. Body roll is pronounced but the driver hardly feels it; the steering remails light, accurate and smooth even near the limit. Even when the tail starts to hang out it does so smoothly, without judder or jerk.” The magazine went on to say that the 230SL “is definitely not The Fastest Thing on Earth”, but concluded the roadtest by commenting, “for the man who can afford it, the 230SL should come near to the ideal of a fast, effortless GT car.”

A Pagoda built in 1963 looks almost identical to the last one from 1971, when the W113 was discontinued to make way for the R107 SL. But there were continual changes throughout the eight years of production, the first important upgrade being the optional five-speed manual gearbox, made by Zahnradfabrik Friedrichshafen (ZF) and which was introduced in May 1966.

The 230SL was offered until 1966, replaced by the 250SL with its 2.5-litre engine. Power output was unchanged, but the M129’s extra capacity allowed around 10 per cent more torque, giving 159lb ft. This engine was fitted with an oil cooler, and other engineering improvements arriving with the 250SL included larger front brake discs, rear discs instead of drums, and a fuel tank increased from 65 to a sizeable 82 litres.

Up until this point all W113s had come with a soft top but presented at the Geneva motor show in March 1967 was a so called Coupe version of the 250SL. This had a removable hardtop but no hood, the extra space freed up by the lack of the hood stowage box allowing rear seats. But this model, with its ‘Code 417’ option and aimed chiefly at the sunny Southern Californian market is rare, and it is not to be confused with regular Pagodas with the optional single, side-mounted rear seat. The 250SL was a short lived model, replaced by the 280SL in early 1968, which with its 2.8-litre engine had 168bhp on tap backed up by 177lb ft torque.

The Pagoda was exotic, but also produced in comparatively large numbers, many of which survive. Increasing affluence throughout the 1960s saw the 280SL achieve the highest production, with 23,885 made compared to 19,381 230SLs and just 5,196 250SLs. There is in fact little difference in the driving experiences the three models offer, but predictably the final, 280SL has emerged as the most coveted, and hence most highly valued one.

Just as the W113 had successfully modernised the SL concept in 1963, by 1971 it was in need of another refresh. The US market in particular – which had been the reason for building the 300SL in the first place – now wanted bigger engines and more luxury, persuading Mercedes to build a successor that was more cruiser than sports car (a V8 powered Pagoda had been experimented with but rejected). It proved to be the right move, the R107 finding well over four times as many customers worldwide as the Pagoda had.

But if the R107 had been Suttgart’s highest selling SL by a huge margin (helped of course by it remaining in production for 18 years) its predecessor has emerged as the most adored of the volume produced generations. The masterpiece Bracq body, the exquisite metal and chrome interior, and driving manners youthful enough to make it seem half its near 60 years add up to one of the most special classic motor cars there are, Mercedes-Benz or otherwise.

W113 restoration

Almost all Pagodas have been rebuilt but many are badly set up, which ruins their fine road manners, David Sutherland is told.

Pagoda’s suspension and engine tuning make them famously trick cars to set up, and a restorer failing to do a proper job in these two areas will deliver a car to an owner – who has no doubt paid a great deal of money – that feels woefully sub-standard. “Many Pagodas fall down on the last five per cent of the restoration – the set up,” says SL Shop’s Bruce Greeham. “The result is usually a miserably driving car that disappointed owners will then store away in their garage and never use.”

This is invariably the result of the Mercedes being worked on by someone lacking the necessary depth of knowledge. “Often the injection timing and the fuel pressures are incorrect.” Bruce explains. “The fuel-injection plunger system has often been recalibrated by a have-a-go mechanic with no W113 expertise fiddling with the fuel mixture settings, and the engine won’t start easily when cold, or when hot.”

It’s the same case with the automatic gearbox, the gearbox oil pressure setting having to be married up with the engine for a good gearshift. The suspension really must be left to an expert too, otherwise it will ride at an incorrect height and if it’s really of out of true will look odd, usually too high. Setting up is complicated by the fact that after new rear suspension springs and dampers are fitted the Pagoda needs time to settle fully.

For Bruce, the very last stage of an invariably long and expensive group-up rebuild – ensuring the car is perfect in every way – is of the utmost important to SL Shop. “Before we hand a car over to a customer, we drive each one 600 to 800 miles in the wet and in the dry to make sure it’s exactly as we want it because there are always a lot of small things to be sorted out.”

Bruce also points out, and laments the fact, that there are now many fully restored, pristine Mercedes classics locked away in garages which are driven only rarely, and that particularly in the case of the W113 SL, this situation does the car no favours at all. “You’ve got to run it at least every month to keep the fuel running through the system,” he says. “I say when you have a car that looks so good, drive it as much as possible and also run it through the cold months and don’t worry if it gets wet.”

It should be a decent long run too, as being started from cold and not allowed to warm up properly will have an adverse effect on all three Pagoda engines, famous for their delicate fuel system. Besides making the engines easier to start next time, regular running prevents oil draining off gearbox seals and making them more likely to leak.

And don’t be timid when you do get the SL out of the garage. “The engines are robust and very revvy, so you can rev the engine hade once warmed up, and drive the car as it was intended to be used.”

How the Mercedes Pagoda evolved

March 1963

230SL introduced at Geneva motor show

May 1966

Five-speed manual gearbox from ZF was made optional

December 1966

250SL replaces 230SL

March 1967

250SL Coupe announced, delivered with hardtop but no canvas hood

January 1968

280SL replaces 250SL

March 1971

W113 range replaced by R107 generation SL

Share With Your Fellow Enthusiasts

CLASSIC MERCEDES Issue 34 Spring 2021

Sports Star!

Bracq’s Mercedes Pagoda still a winner

Article written by Classic Mercedes Editor, David Sutherland

Editorial:

In this issue of Class Mercedes

… Still on convertibles, I’ve driven possibly the best Mercedes Pagoda I’ve ever come across, a late 280SL restored by SLShop. I hope my words on pages 20-26 convey not just how exquisite this particular car is to look at and drive, but how much of a game changer the W113 was when launched 58 years ago…

Cover Story:

Modern World

“ A major W113 innovation was the factory-supplied hardtop, a substantial and strong metal item that was beautifully engineered and styled as the car itself. ”

When launched in 1963 the Mercedes Pagoda (W113) roadster redefined the SL concept, the ultra-modern shape with tis 2.3-litre six-cylinder engine replacing both the 190SL and 300SL.

David Sutherland looks back at how it was received at the time, and drives a beautifully restored last-of-the-line 280SL.

Sensational as the original 300SL of 1954 and the Roadster version launched four years later had been, by the early 1960s Mercedes’ sports cars were no longer doing the whole job needed of them. In the fast modernisation early in that decade curvaceous, aero jet inspired styling was no longer on trend as straight lines and sharp angles became the accepted design cues, and the SL range was even looking ill defined, given that the 190SL and 300SL were very close in styling but a world apart in engineering. As the reporter for Road & Track magazine, Eberhard Seifert, noted in 1963: “The 190SL touring sports car and the high performance 300SL were becoming out of date both technically and in appearance. The last model of the 190SL, seen at the Brussels exhibition, seemed lonely and obsolete. “Some fresh thinking was needed to take the Sport Leicht concept forward – and the W113 series SL presented in March 1963 delivered the goods with flair and fashion.

The all new 230SL logically replaced both the 190SL and 300SL, its 2.3-litre six-cylinder engine making it a mid-point between the underpowered former and the superfast latter. Arguably the high career point of Mercedes-Benz stylist Paul Bracq, its sharp-waisted body with super slim pillars and a huge glass house made the Pagoda probably the freshest looking car in the world at the time (just as the Gullwing has been when unveiled nine years earlier). In the intervening 58 years, the Mercedes Pagoda has become possibly the most loved post-war Mercedes sports car shape, but at the time it was radical, even risky.

Driving the Mercedes Pagoda

Before it was despatched to a new owner in South Africa, David Sutherland took this immaculate 1970 280SL out on the road and enjoyed what he found.

In the nine years I have edited Classic Mercedes magazine, I have been fortunate enough to drive a wide selection of W113 SLs, and this has highlighted that while a Pagoda may look stunning, this is no promise that the quality of the drive matches the appearance. Some feel wonderful and make you long to drive all day, others are dogs you want to hand back as soon as possible.

Thankfully the example seen here is the former. But I knew it would be, because it was a nut and bolt restoration by Warwickshire-based SL Shop, which has considerable Pagoda experience, and which charges enough for its finished work for that to be guaranteed.

Located by SL Shop director Bruce Greetham for a bespoke rebuild for a South African customer, the 1970 280SL was turned up in a barn in Somerset. It had been bought as a wedding present but its sale 20 years later was part of a divorce settlement, by which time it had rusted and generally deteriorated to an unroadworthy condition. Importantly, though, it was a ‘matching numbers’ car (retaining the factory issued engine and chassis numbers), which the customer had insisted on, and was complete.

It had started life in DB180 Silver Grey, but following discussions with Bruch the customer settled on Anthracite Grey (DB172) with red leather. The contrast between the discreet body colour and extrovert interior makes for an intriguing combination, I feel.

The soft, near collapsed seats that have vainly attempted to support the Sutherland frame in many a Pagoda drive were thankfully absent, in their place pert bases and backrests that delivered the ideal height and firmness. The fresh, vivid redness of the seat, dash and steering wheel boss was so delicious I almost wanted to lick it, the same applying to the lovely milk chocolatey wood trim on the dash top and transmission funnel.

An added bonus was the presence of a period correct Becker Mexico four-band radio.

Pagoda engines, if running correctly, should be sharp, raspy and responsive, and this was that and more, although Bruce told me that the pronounced note from the exhaust would calm as the brand new system wore in.

The four speed automatic gearbox, with the odd Mercedes Pagoda gate of Drive three notches forward of Park, shifted quickly if not so smoothly and gave off a small amount of gear whine, but this is hardly an issue on a five-decade old car. The high point of this example’s dynamics was the handling: the springing and damping – often way out on Pagodas – was spot on, providing a delightfully settled ride and absorbing bumps beautifully. The steering, with power-assistance, was crisp and quiet.

Overall this rates as one of the best presented and set up Pagodas I’ve tried. But of course when you write out a cheque for well over £100,000 – Bruce isn’t saying what his customer, an SL Shop regular, paid – no less is expected!

“At first glance we found the upper lines of the compact body to be somewhat shocking,” Seifert wrote in his approval. “However on better acquaintance with this interesting car with all its fascinating detail we grew more and more enthusiastic.” The select group of customers able to afford the 230SL’s price – twice that of a basic Fintail – needed no convincing, the car soon generated a long waiting list for delivery.

With a relatively high production target in mind, the W113 had to be closer in configuration to the 190SL than the 300SL, thus much below the skin came from the Fintail. The Bosch fuel-injected, M127 overhead-camshaft engine was from the 220SE, power pushed up 20 bhp to 147bhp and produced 700rpm higher at 5,500rpm; torque was raised fractionally to 145lb ft. The gearbox was four-speed, manual or automatic. The suspension was also taken from the Fintail, coils and wishbones at the front and a swing-axle at the rear.

The 190SL, assuming the lower half of the Ponton’s monocoque construction, had already carved out a niche as a sports car with a high level of comfort and equipment compared to most other roadsters, which were extremely basic. Stuttgart intended to extend that aspect much further and appeal to customers who wanted an open two-seater than was comfortable as well as sporty. Hence if you compare a W113 to any MG of the time or even a Jaguar E-Type, it feels luxurious. The seats were larger and comfortably padded, and power-assisted steering was optionally available from the start.

A major W113 innovation was the factory-supplied hardtop, a substantial and strong metal item that was a beautifully engineered and styled as the car itself, and which would also be a feature on the subsequent R107 and R129 generations, the tradition ending when the 2002 R230SL arrived with its power-folding metal roof. It wasn’t long before the W113’s lid, with its concave top section designed for structural strength as well as to look pretty, brought the name ‘Pagoda’ (which the factory itself thought up) to this model series.

Safety, not previously associated with sports cars, was an important feature of the W113. Mercedes safety guru Béla Barényi was at the height of his powers and following his creation of the passenger safety cell in the Fintail, applied the same stiff body unit and energy absorbing crash deformation cells to an open car for the first time. Front disc brakes were fitted, still a rare feature on road cars in those days.

This was no bone-jarring, teeth-rattling almost solidly sprung sports car, as Road & Track concluded once it was able to spend more time with the 230SL. “Springing is very, very sort, with excellent damping, and on corners it feels as if the limit could never be reached. Body roll is pronounced but the driver hardly feels it; the steering remails light, accurate and smooth even near the limit. Even when the tail starts to hang out it does so smoothly, without judder or jerk.” The magazine went on to say that the 230SL “is definitely not The Fastest Thing on Earth”, but concluded the roadtest by commenting, “for the man who can afford it, the 230SL should come near to the ideal of a fast, effortless GT car.”

A Pagoda built in 1963 looks almost identical to the last one from 1971, when the W113 was discontinued to make way for the R107 SL. But there were continual changes throughout the eight years of production, the first important upgrade being the optional five-speed manual gearbox, made by Zahnradfabrik Friedrichshafen (ZF) and which was introduced in May 1966.

The 230SL was offered until 1966, replaced by the 250SL with its 2.5-litre engine. Power output was unchanged, but the M129’s extra capacity allowed around 10 per cent more torque, giving 159lb ft. This engine was fitted with an oil cooler, and other engineering improvements arriving with the 250SL included larger front brake discs, rear discs instead of drums, and a fuel tank increased from 65 to a sizeable 82 litres.

Up until this point all W113s had come with a soft top but presented at the Geneva motor show in March 1967 was a so called Coupe version of the 250SL. This had a removable hardtop but no hood, the extra space freed up by the lack of the hood stowage box allowing rear seats. But this model, with its ‘Code 417’ option and aimed chiefly at the sunny Southern Californian market is rare, and it is not to be confused with regular Pagodas with the optional single, side-mounted rear seat. The 250SL was a short lived model, replaced by the 280SL in early 1968, which with its 2.8-litre engine had 168bhp on tap backed up by 177lb ft torque.

The Pagoda was exotic, but also produced in comparatively large numbers, many of which survive. Increasing affluence throughout the 1960s saw the 280SL achieve the highest production, with 23,885 made compared to 19,381 230SLs and just 5,196 250SLs. There is in fact little difference in the driving experiences the three models offer, but predictably the final, 280SL has emerged as the most coveted, and hence most highly valued one.

Just as the W113 had successfully modernised the SL concept in 1963, by 1971 it was in need of another refresh. The US market in particular – which had been the reason for building the 300SL in the first place – now wanted bigger engines and more luxury, persuading Mercedes to build a successor that was more cruiser than sports car (a V8 powered Pagoda had been experimented with but rejected). It proved to be the right move, the R107 finding well over four times as many customers worldwide as the Pagoda had.

But if the R107 had been Suttgart’s highest selling SL by a huge margin (helped of course by it remaining in production for 18 years) its predecessor has emerged as the most adored of the volume produced generations. The masterpiece Bracq body, the exquisite metal and chrome interior, and driving manners youthful enough to make it seem half its near 60 years add up to one of the most special classic motor cars there are, Mercedes-Benz or otherwise.

W113 restoration

Almost all Pagodas have been rebuilt but many are badly set up, which ruins their fine road manners, David Sutherland is told.

Pagoda’s suspension and engine tuning make them famously trick cars to set up, and a restorer failing to do a proper job in these two areas will deliver a car to an owner – who has no doubt paid a great deal of money – that feels woefully sub-standard. “Many Pagodas fall down on the last five per cent of the restoration – the set up,” says SL Shop’s Bruce Greeham. “The result is usually a miserably driving car that disappointed owners will then store away in their garage and never use.”

This is invariably the result of the Mercedes being worked on by someone lacking the necessary depth of knowledge. “Often the injection timing and the fuel pressures are incorrect.” Bruce explains. “The fuel-injection plunger system has often been recalibrated by a have-a-go mechanic with no W113 expertise fiddling with the fuel mixture settings, and the engine won’t start easily when cold, or when hot.”

It’s the same case with the automatic gearbox, the gearbox oil pressure setting having to be married up with the engine for a good gearshift. The suspension really must be left to an expert too, otherwise it will ride at an incorrect height and if it’s really of out of true will look odd, usually too high. Setting up is complicated by the fact that after new rear suspension springs and dampers are fitted the Pagoda needs time to settle fully.

For Bruce, the very last stage of an invariably long and expensive group-up rebuild – ensuring the car is perfect in every way – is of the utmost important to SL Shop. “Before we hand a car over to a customer, we drive each one 600 to 800 miles in the wet and in the dry to make sure it’s exactly as we want it because there are always a lot of small things to be sorted out.”

Bruce also points out, and laments the fact, that there are now many fully restored, pristine Mercedes classics locked away in garages which are driven only rarely, and that particularly in the case of the W113 SL, this situation does the car no favours at all. “You’ve got to run it at least every month to keep the fuel running through the system,” he says. “I say when you have a car that looks so good, drive it as much as possible and also run it through the cold months and don’t worry if it gets wet.”

It should be a decent long run too, as being started from cold and not allowed to warm up properly will have an adverse effect on all three Pagoda engines, famous for their delicate fuel system. Besides making the engines easier to start next time, regular running prevents oil draining off gearbox seals and making them more likely to leak.

And don’t be timid when you do get the SL out of the garage. “The engines are robust and very revvy, so you can rev the engine hade once warmed up, and drive the car as it was intended to be used.”

How the Mercedes Pagoda evolved

March 1963

230SL introduced at Geneva motor show

May 1966

Five-speed manual gearbox from ZF was made optional

December 1966

250SL replaces 230SL

March 1967

250SL Coupe announced, delivered with hardtop but no canvas hood

January 1968

280SL replaces 250SL

March 1971

W113 range replaced by R107 generation SL

Share With Your Fellow Enthusiasts

More from Journal

CARE

THE ULTIMATE CERTIFIED SERVICING INVESTMENT PLAN

Your ownership journey matters to us, which is why we have created a simple certified servicing investment plan, tailored to your individual needs and aspirations.

Start investing today and our dedicated CARE team will work with you to increase the value and enjoyment you receive from your vehicle.

STAY IN TUNE WITH SLSHOP MOMENTS

As part of SLSHOP’s community of enthusiasts, you’ll be the first to hear about events and tours, key product offers, exciting stories from owners around the world and of course… our latest additions to the showroom. So, be the first to know and you might just sneak a car on your driveway or take your car’s condition to new heights with our exclusive replacement parts.

Or, visit SLSHOP Journal