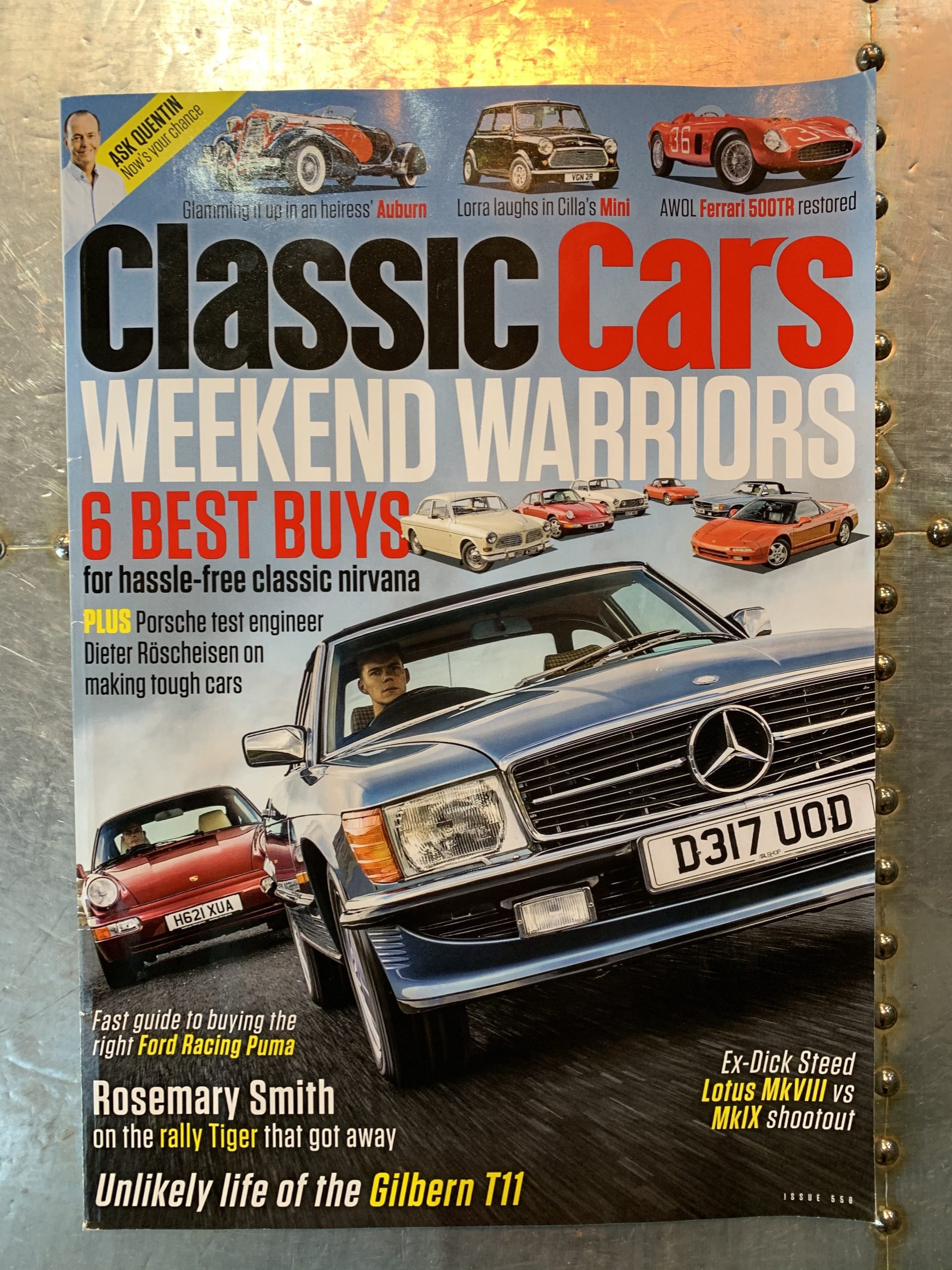

When it comes to buying your next classic, enjoyability and reliability needn’t be considered mutually exclusive. This sporting six are tougher than most – and can be found from £1200 – £46,000.

Photography: Jonathan Jacob Words: Andrew Noakes

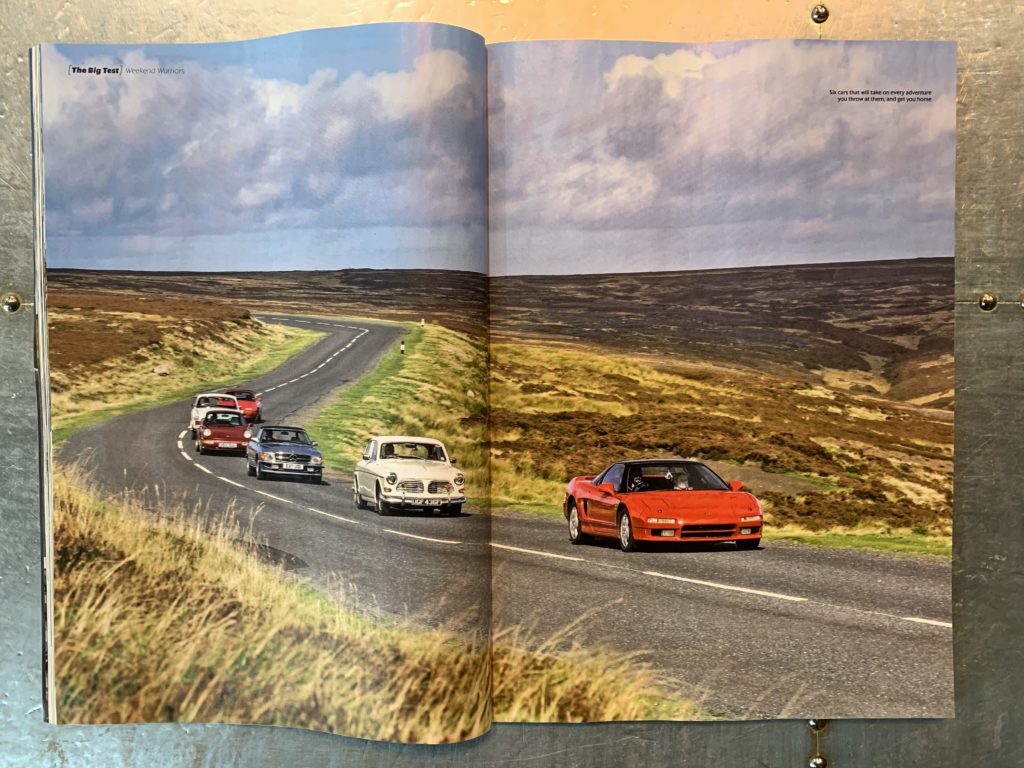

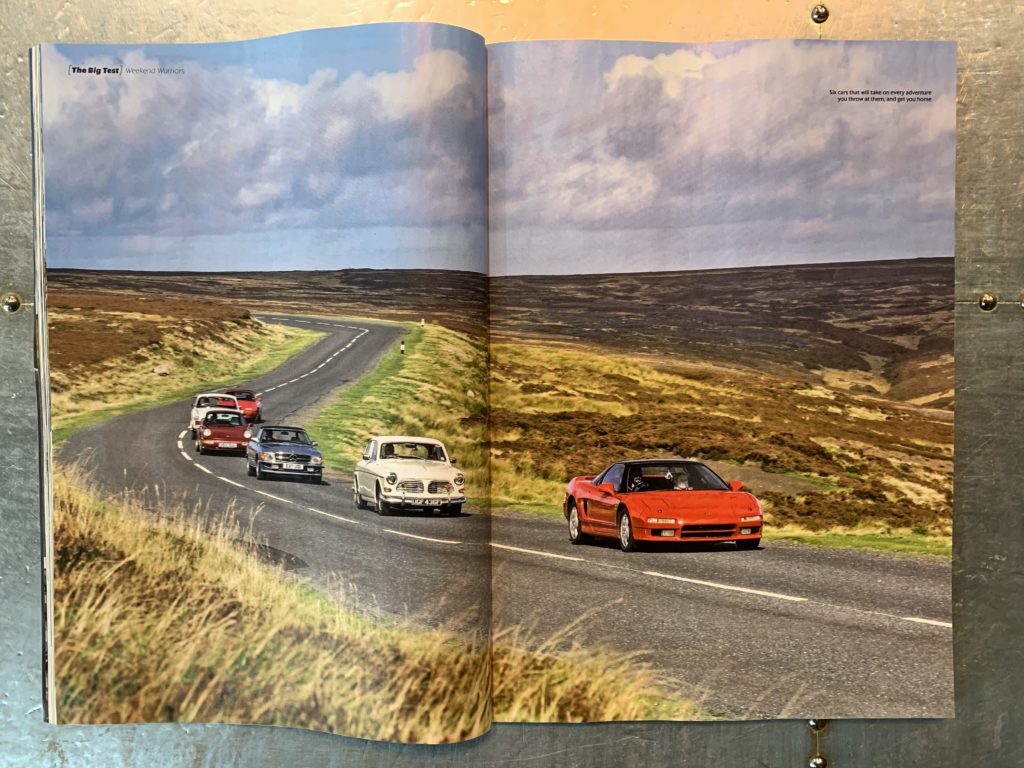

Dependable so often means dull, but does it have to be that way? Can a classic you can rely on still have the kind of engaging character that makes every mile a pleasure? To find out we’ve brought together six cars from marques that know how to build them strong: Mercedes-Benz, Volvo, Porsche, Honda, Bristol and Mazda. There are saloons, coupés and sports cars, each one of them with a reputation for reliability, and between them they have something to offer for budgets from under £5000 to over £50,000. Which of them can deliver not just a hassle-free ownership experience but also a thrilling drive on some of Yorkshire’s most challenging roads? I can’t wait to get behind the wheel of each one to find out.

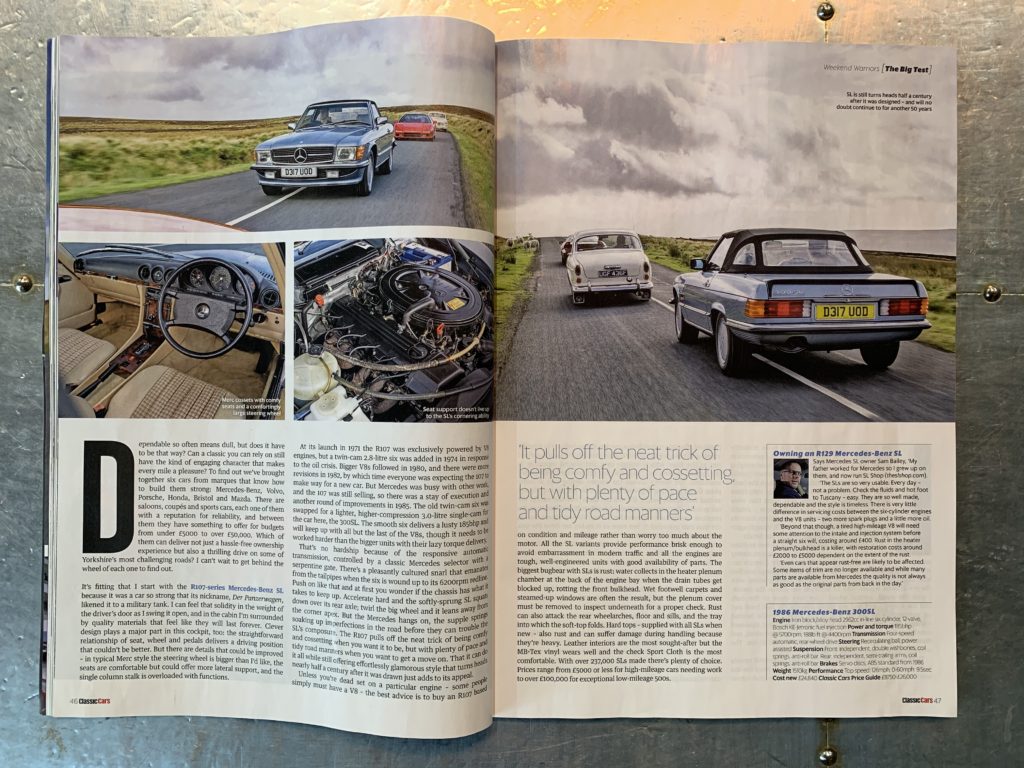

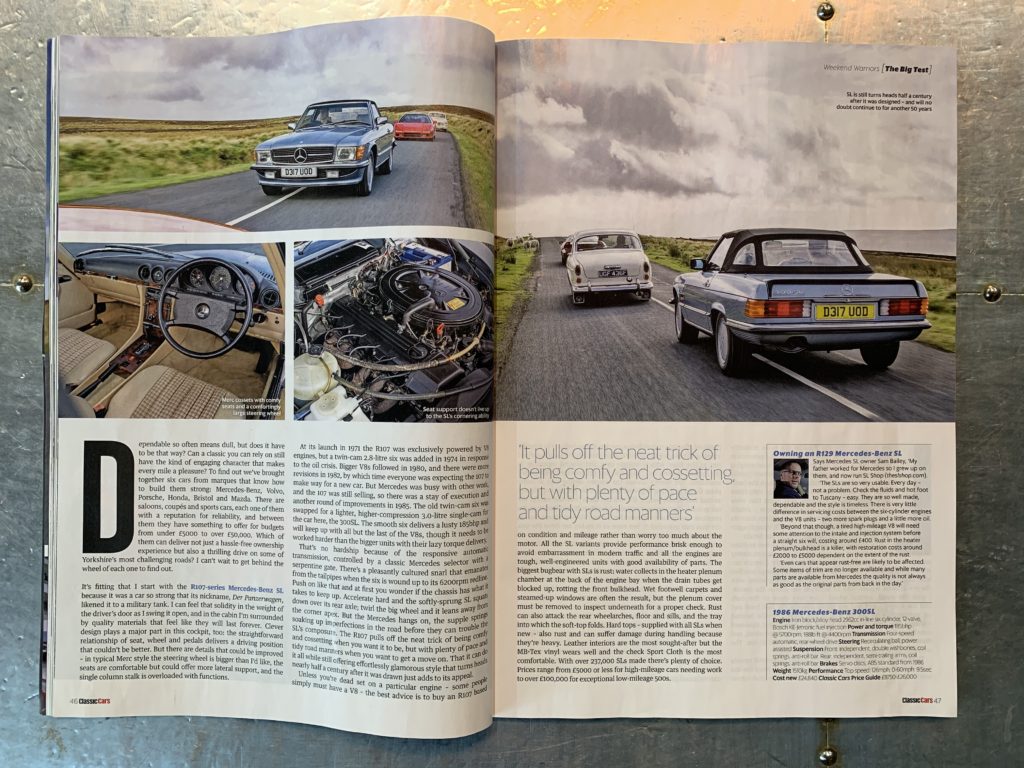

It’s fitting that I start with the R107-series Mercedes-Benz SL because it was a car so strong that its nickname, Der Panzerwagen, likened to a military tank. I can feel that solidity in the weight of the driver’s door as I swing it open, and in the cabin I’m surrounded by quality materials that feel like they will last forever. Clever design plays a major part in this cockpit, too: The straightforward relationship of seat, wheel and pedals delivers a driving position that couldn’t be better. But there are details that could be improved – in typical Merc style the steering wheel is bigger than I’d like, the seats are comfortable but could offer more lateral support, and the single column stalk is overloaded with functions.

At its launch in 1971 the R107 was exclusively powered by V8 engines, but a twin-cam 20.8 litre six was added in 1974 in response to the oil crisis. Bigger V8s followed in 1980, and there were more revisions in 1982, by which time everyone was expecting the 107 to make way for a new car. But Mercedes was busy with other work, and the 107 was still selling, so there was a stay of execution and another round of improvements in 1985. The old twin-cam six was swapped for a lighter, higher-compression 3.0-litre single-cam for the car here, the 300SL. The smooth six delivers a lusty 185bhp and will keep up with all but the last of the V8s, though it needs to be worked harder than the bigger units with their lazy torque delivery.

That’s no hardship because of the responsive automatic transmission, controlled by a classic Mercedes selector with a serpentine gate. There’s a pleasantly cultured snarl that emanates from the tailpipes when the six is wound up to its 6200rpm redline. Push on like that and at first you wonder if the chassis has what it takes to keep up. Accelerate hard and the softly-sprung SL squats down over its rear axle; twirl the big wheel and it leans away from the corner apex. But the Mercedes hangs on, the supple springs soaking up imperfections in the road before they can trouble the SL’s composure. The R107 pulls off the neat trick of being comfy and cosseting when you want it to be, but with plenty of pace and tidy road manners when you want to get a move on. That it can do it all while still offering effortlessly glamorous style that turns heads nearly half a century after it was drawn just adds to its appeal.

Unless you’re dead set on a particular engine – some people simply must have a V8 – the best advice is to buy an R107 based on condition and mileage rather than worry too much about the motor. All the SL variants provide performance brisk enough to avoid embarrassment in modern traffic and all the engines are tough, well-engineered units with good availability of parts. The biggest bugbear with Sls is rust: water collects in the heater plenum chamber at the back of the engine bay when the drain tubes get blocked up, rotting the front bulkhead. Wet foot well carpets and steamed-up windows are often the result, but the plenum cover must be removed to inspect underneath for a proper check. Rust can also attack the rear wheel arches, floor and sills, and the tray into which the soft-top folds. Hard tops – supplied with all the SLs when new – also rust and can suffer damage during handling because they’re heavy. Leather interiors are the most sought-after but the MB-Tex vinyl wears well and the check Sport Cloth is the most comfortable. With over 237,000 Sls made there’s plenty of choice. Prices range from £5000 or less for high-mileage cars needing work to over £100,000 for exceptional low-mileage 500s.

| Owning an R129 Mercedes-Benz SL Says Mercedes SL owner Sam Bailey, ‘My father worked for Mercedes so I grew up on them, and now run SL Shop (theslshop.com). ‘The Sls are so very usable. Every day – not a problem. Check the fluids and hot foot to Tuscany – easy. They are so well made, dependable and the style is timeless. There is very little difference in servicing costs between the six-cylinder engines and the V8 units – two more spark plugs and a little more oil. Beyond that though, a tired high-mileage V8 will need some attention to the intake and injection system before a straight six will, costing around £400. Rust in the heater plenum/bulkhead is a killer, with restoration costs around £2000 – £5000 dependent on the extent of the rust. Even cars that appear rust-free are likely to be affected. Some items of trim are no longer available and while many parts are available from Mercedes the quality is not always as good as the original parts from back in the day.’ |

| 1986 Mercedes-Benz 300SL Engine: Iron block/alloy head 2962cc in-line cylinder, 12 valve Bosch KE-Jetronic fuel injection. Power and torque 185bhp @ 5700rpm 188lb ft @ 4400rpm. Transmission Four speed automatic, rear-wheel drive. Steering Recirculating ball, power-assisted. Suspension Front Independent double wishbones, coil springs, anti-roll bar. Rear Independent semi-trailing arms, coil springs, anti-roll bar. Brakes Servo discs, ABS standard from 1986. Weight 1510kg. Performance Top Speed 126mph, 0-60mph 95sec. Cost new £24,840. Classic Cars Price Guide £8750 – £26,000 |

Like the Mercedes, the Porsche 911 is an instantly recognisable shape, even though the 964 generation introduced in 1989 had brought the widest-ranging changes ever to the Neunelfer. The revised model was said to be 85 per cent new, and though the basic shape was the same as it had been since 1963 there were smoothed-out bumpers, rear lights that were new and bigger, and a pop-up rear spoiler – details the made the 964 look far more modern than its predecessors. The cabin was reworked, though again the innovations were only apparent in the details.

It’s a snug cabin with room enough for two tiny rear seats that are only capable of accommodating young children or a compressed adult. Subsidiary controls are strewn haphazardly across the dashboard, but the orange needled instruments are clustered tidily behind the steering wheel with the rev counter replete with its 6750rpm red line in the centre. I grab the small, vertical wheel – set very close to the dash and the screen – and find my hands obscure the fuel level and oil temperature gauges, as well as the speedo needle beyond 100mph. The floor-hinged pedals are well spaced but squeezed over towards the centre of the car by the wheel-arch intrusion, and there’s nowhere to rest my clutch foot when it’s not in use. The whole thing is an off mixture of clarity and chaos.

The same could be said of the 964’s handling. At normal speeds it feels glued to the road, the ride firm enough to keep the car level but with strong enough suppleness to be unaffected by mid-corner potholes. The 964 responds in a precise, measured way to steering inputs and there’s masses of feedback through the steering wheel rim as the front wheels wriggle over and around asperities in the tarmac, despite this being the first 911 provided with power assistance. Yet there’s always the uneasy feeling that at some point driver ambition might be overruled by the laws of physics as that rear-biased weight distribution takes over and swings the tail around. The new suspension – by coil springs rather than the previous torsion bars – means that its a less likely prospect than in the 911s that preceded it, but even so it makes me drive the 964 with a healthy dose of respect.

At its best, its most stable, when braked in good time in a straight line and then powered out of the corners. Part of the 964’s newness was a thoroughly revamped engine, expanded to 3.6 litres over the previous 3.2, with new cylinder heads and a heavily modified block. With 250bhp on tap it was the most powerful non-turbo 911 yet made. The motor grumbles away at idle with a seething intent and on the road you’re always aware of it’s presence. Push it hard and the cabin fills with a gloriously purposeful wail that’s an inextricable part of the 911 appeal.

Though these are robust cars, there are weak points. Externally the body suffers from stone chips at the front and solid paint colours fade. Superficial rust can form around the front and rear screen apertures and more serious rot can attack the rear suspension pick-up points necessitating long and complex repairs. It’s important to look for signs of accident damage repairs such as uneven panel gaps and rippled panels under the front boot carpet.

Check for soggy interior carpets on cabrios and Targas as both can suffer from roof leaks. A cabrio roof can cost £2000 to replace. The engines commonly suffer from oil leaks, but if the leak is bad or accompanied by a misfire a cylinder head stud might have broken. A head rebuild using genuine parts will cost around £7000.

Most cars were manuals, with early ones having dual-mass flywheels which can wear and cost £1000 to replace. Tiptronic automatics are usually trouble-free although the torque converters can fail with noisy consequences. Air conditioning was a rare extra which cost £2000 on a new car and will need £1000 spent on it now unless it has had a recent rebuild. Check windows, mirrors and (if fitted) electric seat adjusters all work, because replacement parts are expensive. Cabrios, Targas and Tiptronics are worth less, starting at around £15,000 for cars that need work. Good coupés start around £50,000 and the best can be over £80,000. Turbos and RS models will be twice as much or more, so the non-turbo Carreras are where the value is.

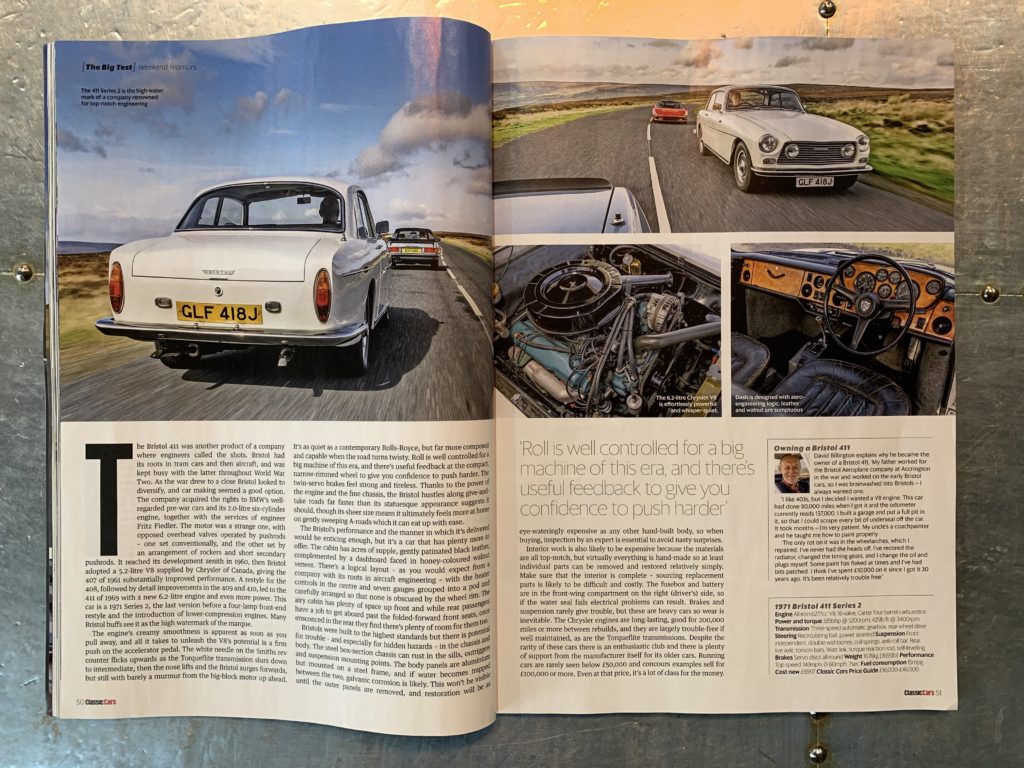

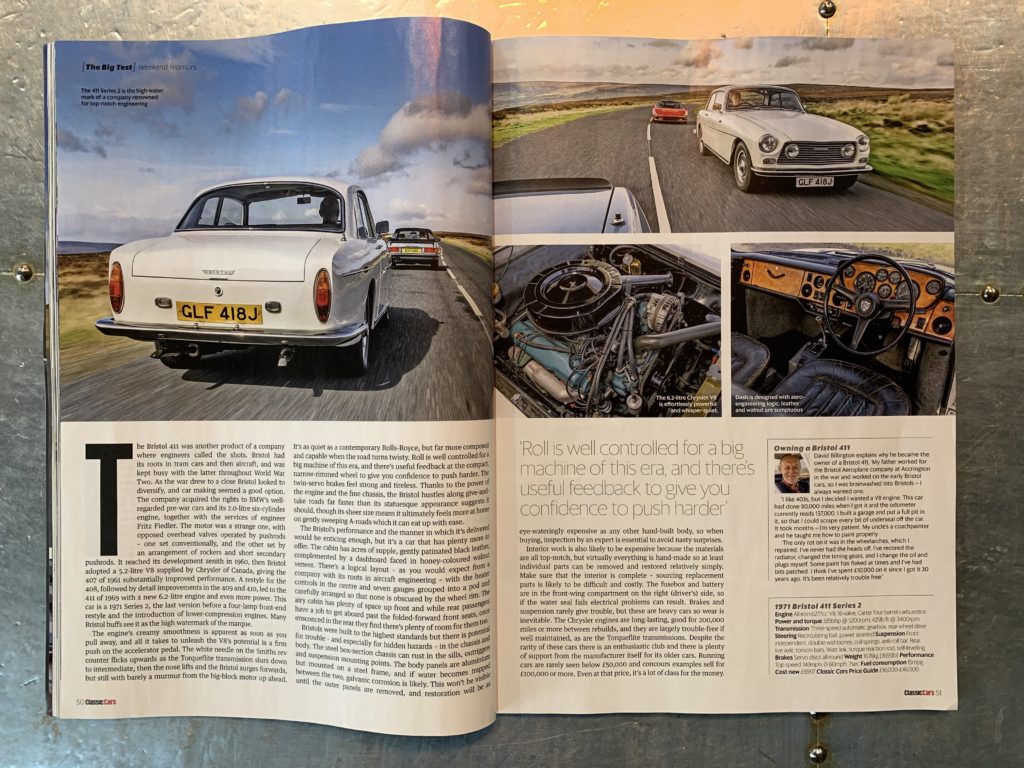

The Bristol 411 was another product of a company where engineers called the shots. Bristol had its roots in tram cars and the aircraft, and was kept busy with the latter throughout World War Two. As the war drew to a close Bristol looked to diversify, and car making seemed a good option. The company acquired the rights to BMW’s well-regarded pre-war cars and its 2.0 litre six-cylinder engine, together with the services of engineer Fritz Fiedler. The motor was a strange one, with opposed overhead valves operated by pushrods – one set conventionally, and the other set by an arrangement of rockers and short secondary pushrods. It reached its development zenith in 1960, then Bristol adopted a 5.2 litre V8 supplied by Chrysler of Canada, giving the 407 of 1961 substantially improved performance. A restyle for the 408, followed by detailed improvements in the 409 and 410, led to the 411 of 1969 with a new 6.2 litre engine and even more power. This car is a 1971 Series 2, the last version before a four-lamp front-end restyle and the introduction of lower-compression engines. Many Bristol buff’s see it as the high watermark of the marque.

The engine’s creamy smoothness is apparent as soon as you pull away, and all it takes to unleash the V8’s potential is a firm push on the accelerator pedal. The white needle on the Smiths rev counter flicks upwards as the Torqueflite transmission slurs down to intermediate, then the nose lifts and the Bristol surges forwards, but still with a barely a murmur from the big-block motor up ahead. It’s as quiet as a contemporary Rolls-Royce, but far more composed and capable when the road turns twisty. Roll is well controlled for a big machine of this era, and there’s useful feedback at the compact, narrow-rimmed wheel to give you confidence to push harder. The twin-servo brakes feel strong and tireless. Thanks to the power of the engine and the fine chassis, the Bristol hustles along give-and-take roads far faster than its statuesque appearance suggests it should, though its sheer size means it ultimately feels more at home on gently sweeping A-roads which it can eat up with ease.

The Bristol’s performance and the manner in which it’s delivered would be enticing enough, but its a car that has plenty more to offer. The cabin has acres of supple, gently patinated black leather, complemented by a dashboard faced in honey-coloured walnut veneer. There’s a logical layout – as you would expect from a company with its roots in aircraft engineering – with the heater controls in the centre and seven gauges grouped into a pod and carefully arranged so that none is obscured by the wheel rim. The airy cabin has plenty of space up front and while rear passengers have a job to get aboard past the folder-forward front seats, once ensconced in the rear they find there’s plenty of room for them too.

Bristols were built to the highest standards but there is a potential for trouble – and especially for hidden hazards – in the chassis and body. The steel box-section chassis can rust in the sills, outriggers and suspension mounting points. The body panels are aluminium but mounted on a steel frame, and if water becomes trapped between the two, galvanic corrosion is likely. This wont be visible until the outer panels are removed, and restoration will be as eye-wateringly expensive as any other hand-built body, so when buying, inspection by an expert is essential to avoid any nasty surprises.

Interior work is also likely to be expensive because the materials are all top-notch, but virtually everything is handmade so at least individual parts can be removed and restored relatively simply. Make sure that the interior is complete – sourcing replacement parts is likely to be difficult and costly. The fuse box and battery are in the front-wing compartment on the right (driver’s) side, so if the water seal fails electric problems can result. Brakes and suspension rarely give trouble, but these are heavy cars so wear is inevitable. The Chrysler engines are long-lasting, good for 200,000 miles or more between rebuilds, and they are largely trouble-free if well maintained, as are the Torqueflite transmissions. Despite the rarity of these cars there is an enthusiastic club and there is plenty of support from the manufacturer itself for older cars. Running cars are rarely seen below £50,000 and concours examples sell for £100,000 or more. Even at that price, it’s a lot of class for the money.

Although the Honda NSX is a very different car, from a different era, it shares a good deal of the Bristol’s ethos. Like the older car it was designed to offer plenty of space, it is packed with quality engineering and its intelligent design makes it no more difficult to drive or own than a Civic. The aluminium alloy structure was a first on a volume-production car and its clothes in a dramatic, cab-forward shape with a long rear deck and huge wing which make a compelling statement of Honda’s intent. This was the Japanese company’s answer to exotica like the Ferrari 328 and Lamborghini Jalpa. Honda aimed to beat the Italians at their own game, offering all the thrills of the established junior super cars but with a painless ownership experience thrown in for good measure.

Hidden in the black pillar at the back of the door, just above the waistline, is a fingertip-operated latch for the wide, frameless door. It opens onto a black interior which has grippy-looking sports seats, but nothing much else of note. Its all nicely but together but the materials don’t look very special, and the steering wheel could have come from the Accord my dad ran in the Eighties. But the driving position is good and the view out is superb, framed at the front by the humps of the wings and with plenty of vision to the rear, which is unusual for a mid-engined car. The clutch is light and the alloy-knobbed gear lever slots easily into first. At sensible speeds the NSX turns out to be as easy to drive as that Accord. Yet there are signs that it has more to come. The 8000rpm redline on the tacho is one indication, the ominous burble from the non-standard straight-through exhaust on this car another. The steering is unassisted, and as the speed builds it faithfully transmits messages back from the front tyres. The NSX is easy to place on the road and it corners flat and fast; as the road opens out, the V6s mid-range snarl turns into an F1-style wail that builds and builds as the revs climb. The 3.0 litre V6 pulls strongly all the way, the torque curve bolstered by variable valve timing and lift electronic control (VTEC) and a variable income intake (VVIS) and not reaching peak torque until 6500rpm with peak power just 800rpm further on.

Its then that the NSX starts to make sense. Thoughts of the cabin being humdrum and the engine having two cylinders too few evaporate as I start to understand what an effective driving tool this is. Famously Ayrton Senna contributed to its development, and Honda also called upon the services of Japan’s first full-time F1 driver Satoru Nakajima and multiple IndyCar champion Bobby Rahal. It worked; The steering is precise and communicative, and the NSX feels compact and balanced. The engine is responsive and flexible without being so strong that it becomes an embarrassment, though the open exhaust on this car certainly attracts plenty of attention. The NXS is a modern classic that would work as everyday transport, but point it at these empty and enticingly twisty Yorkshire moors roads and it delivers driving thrills aplenty.

Suspension bushes and ball joints can suffer from hard use, and to replace the lower front ball joint you need an entire upright at a cost of in excess £1000. The engines can sometimes suffer from top-end oil leaks and should have the timing belt, camshaft pulley and water pump changed every seven years or 70,000 miles – a £2000 job. Check the coolant expansion tank and hoses for cracks and wear. Noise from the gearbox when in neutral with the clutch engaged can be a failing input shaft bearing. Early gearboxes can fail because of a broken countershaft bearing snap ring, but most will have been sorted out by now. A clutch change is an engine-out job costing £2000. Check for signs of accident repair and evidence that any work has been carried out by an expert, because refinishing the aluminium body has to be done properly to avoid further problems. Headlights are expensive on both the early cars with pop-up units and December 2001-on examples with fixed lights. High-mileage cars and the less-fancied autos and targas start around £30,000, with good manual cars around £50,000. NSXs from 1997 with the 3.2 litre engine and six-speed gearbox can go for £100,000 or more. The prices of all cars, particularly low-mileage manuals, have increased rapidly in recent years.

The Mazda MX-5 is a perennial bargain. It revitalised the market for affordable sports cars which had been in limbo for years following proposals to ban open roadsters from the US market. Thankfully that never happened, and the MX-5 arrived in 1989 after being conceived by Mazda’s Bob Hall in the US in the early Eighties, when rear-drive two-seat roadsters were thin on the ground. Design teams in Tokyo and Irvine California, produced competing concepts with the American design making it to production. Inspired by the Lotus Elan it was in truth quite a different kind of car – bigger and heavier, much more robustly constructed, safer and easier to live with. But it was also great fun to drive, and so it remains 30 years on.

Settling into David Gange’s 1991 car, I notice that the shapely seats have been retrimmed in leather, which some dealers did in period in response to customer demand to add a touch of class to the cabin. It looks good, thought I think there’s something to be said for the warmth of the original cloth. But the cockpit remains a snug place with just enough space for two, and its all the better for being beautifully simple. Clear white on black instruments sit in a binnacle on top of the facia behind a leather trimmed Momo three-spoke steering wheel. Little force is required at the wheel rim and that’s matched by the rest of the controls, making the MX-5 as easy to drive as an Japanese super-mini. Power-assisted steering was common, but not universal on the MX-5 MK1, and it helps when parking while doing little to hinder the flow of feedback on the move. The helm is precise and direct, and I can flick the little Mazda into bends with little effort. Tiny tyres – 185/60 x 14s on 5.5 rims – mean grip levels are never very high, so the Mx-5 can be steered on the throttle where the situation allows. Weight distribution is virtually 50:50 with driver aboard, contributing to the innate balance that makes the Mazda such a joy to drive. It doesn’t have the scalpel-like sharpness to its handling that characterises an Elan or a Toyota MR2, say, but it has a poise that makes tackling a switchback both simple and rewarding.

Extracting the most from the engine takes a bit more work, using the five-speed gearbox with its light, short-throw lever to keep it spinning hard. With 1114bhp propelling just over a tonne, the MX-5 is never going to be lightening quick in a straight line – but its fast enough to be fun. More power was available through Brodie Brittain Racing, which offered a turbo kit, and from 1994 the MX-5 gained a more powerful (128bhp) 1.8 litre engine, a longer final drive, bigger front discs and additional body stiffening, but some enthusiasts prefer the earlier cars. Many ex-Japanese market Eunos Roadsters have been imported – they are virtually identical to MX-5s, but often have air con and a metric odometer. Automatic transmission was a rare option in Japan and the US but not available in the UK.

The engines are reliable and will usually last beyond 100,000 miles if well maintained, though the earliest cars are known for crankshaft wear. Minor oil leaks from the cam cover are common. Clutches last well unless abused and gear changing problems are usually down to a failing slave cylinder which is easily fixed. Springs can corrode and crack, but generally the light overall weight of the MX-5 gives the running gear little trouble. Only the last MK1 cars were offered with ABS. Windows can stick in the runners, but cleaning and lubrication are all the remedy that is required. The convertible roof lasts well, though seals can deteriorate over time and the windscreen header rail clips can wear. Its important to raise and lower the roof when checking a potential purchase to ensure all the parts are present and work correctly. Rust can attack the wheel arches, sills, floors and A-pillar bases. Its important to ensure drain holes in the body and doors are kept clear to avoid rot.

Project cars can be had for £1000 and even the best MK1 MX-5s rarely sell for much beyond £5000, so they’re still very affordable. Though 400,000 of the first generation were built before it was replaced by the MKII in 1998, completely standard cares are becoming scarce. Owner David Gange says the lively MK-5 community is one of the highlights of owning the car, with a thriving owner’s club and Facebook groups like the ‘Bunch of Fives’.

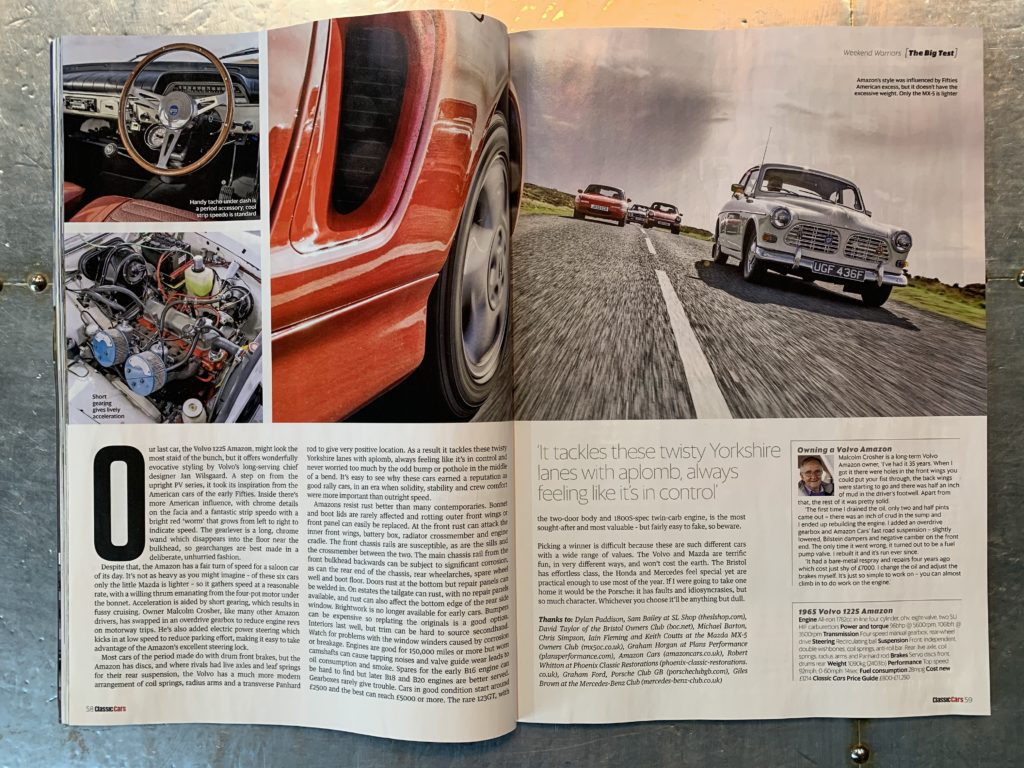

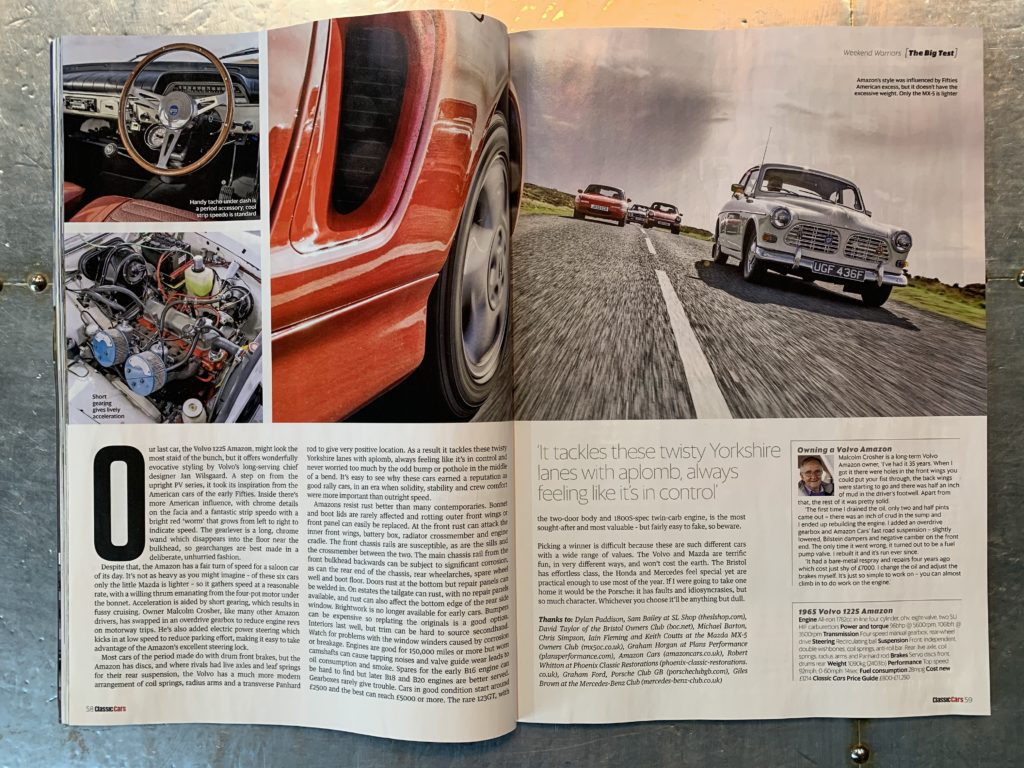

Our last car, the Volvo 1225 Amazon, might look the most staid of the bunch, but it offers wonderfully evocative styling by Volvo’s long-serving chief designer Jan Wilsgaard. A step on from the upright PV series, it took its inspiration from the American cars of the early Fifties. Inside there’s more American influence, with chrome details on the facia and a fantastic strip speedo with a bright red ‘worm’ that grows from left to right to indicate speed. The gear lever is a long, chrome wand which disappears into the floor near the bulkhead, so gear changes are best made in a deliberate, unhurried fashion.

Despite that, the Amazon has a fair turn of speed for a saloon car of its day. Its not as heavy as you might imagine – of these six cars, only the little Mazda is lighter – so it gathers speed at a reasonable rate, with a willing thrum emanating from the four-pot motor under the bonnet. Acceleration is aided by short gearing, which results in fussy cruising. Owner Malcolm Crosher, like many other Amazon drivers, has swapped in an overdue gearbox, to reduce engine revs on motorway trips. He’s also added electric power steering which kicks in at a low speed to reduce parking effort, making it easy to take advantage of the Amazon’s excellent steering lock.

Most cars of the period made do with drum foot brakes, but the Amazon has discs, and where rivals had live axles and leaf springs for their rear suspension, the Volvo has a much more modern arrangement of coil springs, radium arms and a transverse Panhard rod to give very positive location. As a result it tackles these twisty Yorkshire lanes with aplomb, always feeling like its in control and never worried too much by the odd bump or pothole in the middle of a bend. It’s easy to see why these cars earned a reputation as good rally cars, in an era when soliduty, stability and crew comfort were more important than outright speed.

Amazons resist rust better than many contemporaries. Bonnet and boot lids are rarely affected and rotting outer front wings or front panel can easily be replaced. At the front rust can attack the inner front wings, battery box, radiator crossmember and engine cradle. The front chassis rails are susceptible, as are the sills and crossmember between the two. The main chassis rail from the front bulkhead backwards can be subject to significant corrosion, as can the rear end of the chassis, rear wheel arches, spare wheel well and boot floor. Doors rust at the bottom but repair panels can be welded in. On estates, the tailgate can rust, with no repair panels available, and rust can also affect the bottom edge of the rear side window. Brightwork is no longer available for early cars. Bumpers can be expensive so re plating the originals can be a good option. Interiors last well, but trim can be hard to source second hand. Watch for problems with the window winders caused by corrosion or breakage. Engines are good for 150,000 miles or more but work camshafts can cause tapping noises and valve guide wear leads to oil consumption and smoke. Spares for the early B16 engine can be hard to find but later B18 and B20 engines are better served. Gearboxes rarely give trouble. Cars in good condition start around £2500 and the best can reach £5000 or more. The rare 123GT, with the two-door body and 1800S-spec twin-carb engine, is the most sought-after and most valuable – but fairly easy to fake, so beware.

Picking a winner is difficult because these are such different cars with a wide range of values. The Volvo and Mazda are terrific fun, in very different ways, and wont cost the earth. The Bristol has effortless class, the Honda and Mercedes feel special yet are practical enough to use most of the year. If I were going to take one home it would have to be the Porsche: it has faults and idiosyncrasies, but no much character. Whichever you choose it’ll be anything but dull.

When it comes to buying your next classic, enjoyability and reliability needn’t be considered mutually exclusive. This sporting six are tougher than most – and can be found from £1200 – £46,000.

Photography: Jonathan Jacob Words: Andrew Noakes

Dependable so often means dull, but does it have to be that way? Can a classic you can rely on still have the kind of engaging character that makes every mile a pleasure? To find out we’ve brought together six cars from marques that know how to build them strong: Mercedes-Benz, Volvo, Porsche, Honda, Bristol and Mazda. There are saloons, coupés and sports cars, each one of them with a reputation for reliability, and between them they have something to offer for budgets from under £5000 to over £50,000. Which of them can deliver not just a hassle-free ownership experience but also a thrilling drive on some of Yorkshire’s most challenging roads? I can’t wait to get behind the wheel of each one to find out.

It’s fitting that I start with the R107-series Mercedes-Benz SL because it was a car so strong that its nickname, Der Panzerwagen, likened to a military tank. I can feel that solidity in the weight of the driver’s door as I swing it open, and in the cabin I’m surrounded by quality materials that feel like they will last forever. Clever design plays a major part in this cockpit, too: The straightforward relationship of seat, wheel and pedals delivers a driving position that couldn’t be better. But there are details that could be improved – in typical Merc style the steering wheel is bigger than I’d like, the seats are comfortable but could offer more lateral support, and the single column stalk is overloaded with functions.

At its launch in 1971 the R107 was exclusively powered by V8 engines, but a twin-cam 20.8 litre six was added in 1974 in response to the oil crisis. Bigger V8s followed in 1980, and there were more revisions in 1982, by which time everyone was expecting the 107 to make way for a new car. But Mercedes was busy with other work, and the 107 was still selling, so there was a stay of execution and another round of improvements in 1985. The old twin-cam six was swapped for a lighter, higher-compression 3.0-litre single-cam for the car here, the 300SL. The smooth six delivers a lusty 185bhp and will keep up with all but the last of the V8s, though it needs to be worked harder than the bigger units with their lazy torque delivery.

That’s no hardship because of the responsive automatic transmission, controlled by a classic Mercedes selector with a serpentine gate. There’s a pleasantly cultured snarl that emanates from the tailpipes when the six is wound up to its 6200rpm redline. Push on like that and at first you wonder if the chassis has what it takes to keep up. Accelerate hard and the softly-sprung SL squats down over its rear axle; twirl the big wheel and it leans away from the corner apex. But the Mercedes hangs on, the supple springs soaking up imperfections in the road before they can trouble the SL’s composure. The R107 pulls off the neat trick of being comfy and cosseting when you want it to be, but with plenty of pace and tidy road manners when you want to get a move on. That it can do it all while still offering effortlessly glamorous style that turns heads nearly half a century after it was drawn just adds to its appeal.

Unless you’re dead set on a particular engine – some people simply must have a V8 – the best advice is to buy an R107 based on condition and mileage rather than worry too much about the motor. All the SL variants provide performance brisk enough to avoid embarrassment in modern traffic and all the engines are tough, well-engineered units with good availability of parts. The biggest bugbear with Sls is rust: water collects in the heater plenum chamber at the back of the engine bay when the drain tubes get blocked up, rotting the front bulkhead. Wet foot well carpets and steamed-up windows are often the result, but the plenum cover must be removed to inspect underneath for a proper check. Rust can also attack the rear wheel arches, floor and sills, and the tray into which the soft-top folds. Hard tops – supplied with all the SLs when new – also rust and can suffer damage during handling because they’re heavy. Leather interiors are the most sought-after but the MB-Tex vinyl wears well and the check Sport Cloth is the most comfortable. With over 237,000 Sls made there’s plenty of choice. Prices range from £5000 or less for high-mileage cars needing work to over £100,000 for exceptional low-mileage 500s.

| Owning an R129 Mercedes-Benz SL Says Mercedes SL owner Sam Bailey, ‘My father worked for Mercedes so I grew up on them, and now run SL Shop (theslshop.com). ‘The Sls are so very usable. Every day – not a problem. Check the fluids and hot foot to Tuscany – easy. They are so well made, dependable and the style is timeless. There is very little difference in servicing costs between the six-cylinder engines and the V8 units – two more spark plugs and a little more oil. Beyond that though, a tired high-mileage V8 will need some attention to the intake and injection system before a straight six will, costing around £400. Rust in the heater plenum/bulkhead is a killer, with restoration costs around £2000 – £5000 dependent on the extent of the rust. Even cars that appear rust-free are likely to be affected. Some items of trim are no longer available and while many parts are available from Mercedes the quality is not always as good as the original parts from back in the day.’ |

| 1986 Mercedes-Benz 300SL Engine: Iron block/alloy head 2962cc in-line cylinder, 12 valve Bosch KE-Jetronic fuel injection. Power and torque 185bhp @ 5700rpm 188lb ft @ 4400rpm. Transmission Four speed automatic, rear-wheel drive. Steering Recirculating ball, power-assisted. Suspension Front Independent double wishbones, coil springs, anti-roll bar. Rear Independent semi-trailing arms, coil springs, anti-roll bar. Brakes Servo discs, ABS standard from 1986. Weight 1510kg. Performance Top Speed 126mph, 0-60mph 95sec. Cost new £24,840. Classic Cars Price Guide £8750 – £26,000 |

Like the Mercedes, the Porsche 911 is an instantly recognisable shape, even though the 964 generation introduced in 1989 had brought the widest-ranging changes ever to the Neunelfer. The revised model was said to be 85 per cent new, and though the basic shape was the same as it had been since 1963 there were smoothed-out bumpers, rear lights that were new and bigger, and a pop-up rear spoiler – details the made the 964 look far more modern than its predecessors. The cabin was reworked, though again the innovations were only apparent in the details.

It’s a snug cabin with room enough for two tiny rear seats that are only capable of accommodating young children or a compressed adult. Subsidiary controls are strewn haphazardly across the dashboard, but the orange needled instruments are clustered tidily behind the steering wheel with the rev counter replete with its 6750rpm red line in the centre. I grab the small, vertical wheel – set very close to the dash and the screen – and find my hands obscure the fuel level and oil temperature gauges, as well as the speedo needle beyond 100mph. The floor-hinged pedals are well spaced but squeezed over towards the centre of the car by the wheel-arch intrusion, and there’s nowhere to rest my clutch foot when it’s not in use. The whole thing is an off mixture of clarity and chaos.

The same could be said of the 964’s handling. At normal speeds it feels glued to the road, the ride firm enough to keep the car level but with strong enough suppleness to be unaffected by mid-corner potholes. The 964 responds in a precise, measured way to steering inputs and there’s masses of feedback through the steering wheel rim as the front wheels wriggle over and around asperities in the tarmac, despite this being the first 911 provided with power assistance. Yet there’s always the uneasy feeling that at some point driver ambition might be overruled by the laws of physics as that rear-biased weight distribution takes over and swings the tail around. The new suspension – by coil springs rather than the previous torsion bars – means that its a less likely prospect than in the 911s that preceded it, but even so it makes me drive the 964 with a healthy dose of respect.

At its best, its most stable, when braked in good time in a straight line and then powered out of the corners. Part of the 964’s newness was a thoroughly revamped engine, expanded to 3.6 litres over the previous 3.2, with new cylinder heads and a heavily modified block. With 250bhp on tap it was the most powerful non-turbo 911 yet made. The motor grumbles away at idle with a seething intent and on the road you’re always aware of it’s presence. Push it hard and the cabin fills with a gloriously purposeful wail that’s an inextricable part of the 911 appeal.

Though these are robust cars, there are weak points. Externally the body suffers from stone chips at the front and solid paint colours fade. Superficial rust can form around the front and rear screen apertures and more serious rot can attack the rear suspension pick-up points necessitating long and complex repairs. It’s important to look for signs of accident damage repairs such as uneven panel gaps and rippled panels under the front boot carpet.

Check for soggy interior carpets on cabrios and Targas as both can suffer from roof leaks. A cabrio roof can cost £2000 to replace. The engines commonly suffer from oil leaks, but if the leak is bad or accompanied by a misfire a cylinder head stud might have broken. A head rebuild using genuine parts will cost around £7000.

Most cars were manuals, with early ones having dual-mass flywheels which can wear and cost £1000 to replace. Tiptronic automatics are usually trouble-free although the torque converters can fail with noisy consequences. Air conditioning was a rare extra which cost £2000 on a new car and will need £1000 spent on it now unless it has had a recent rebuild. Check windows, mirrors and (if fitted) electric seat adjusters all work, because replacement parts are expensive. Cabrios, Targas and Tiptronics are worth less, starting at around £15,000 for cars that need work. Good coupés start around £50,000 and the best can be over £80,000. Turbos and RS models will be twice as much or more, so the non-turbo Carreras are where the value is.

The Bristol 411 was another product of a company where engineers called the shots. Bristol had its roots in tram cars and the aircraft, and was kept busy with the latter throughout World War Two. As the war drew to a close Bristol looked to diversify, and car making seemed a good option. The company acquired the rights to BMW’s well-regarded pre-war cars and its 2.0 litre six-cylinder engine, together with the services of engineer Fritz Fiedler. The motor was a strange one, with opposed overhead valves operated by pushrods – one set conventionally, and the other set by an arrangement of rockers and short secondary pushrods. It reached its development zenith in 1960, then Bristol adopted a 5.2 litre V8 supplied by Chrysler of Canada, giving the 407 of 1961 substantially improved performance. A restyle for the 408, followed by detailed improvements in the 409 and 410, led to the 411 of 1969 with a new 6.2 litre engine and even more power. This car is a 1971 Series 2, the last version before a four-lamp front-end restyle and the introduction of lower-compression engines. Many Bristol buff’s see it as the high watermark of the marque.

The engine’s creamy smoothness is apparent as soon as you pull away, and all it takes to unleash the V8’s potential is a firm push on the accelerator pedal. The white needle on the Smiths rev counter flicks upwards as the Torqueflite transmission slurs down to intermediate, then the nose lifts and the Bristol surges forwards, but still with a barely a murmur from the big-block motor up ahead. It’s as quiet as a contemporary Rolls-Royce, but far more composed and capable when the road turns twisty. Roll is well controlled for a big machine of this era, and there’s useful feedback at the compact, narrow-rimmed wheel to give you confidence to push harder. The twin-servo brakes feel strong and tireless. Thanks to the power of the engine and the fine chassis, the Bristol hustles along give-and-take roads far faster than its statuesque appearance suggests it should, though its sheer size means it ultimately feels more at home on gently sweeping A-roads which it can eat up with ease.

The Bristol’s performance and the manner in which it’s delivered would be enticing enough, but its a car that has plenty more to offer. The cabin has acres of supple, gently patinated black leather, complemented by a dashboard faced in honey-coloured walnut veneer. There’s a logical layout – as you would expect from a company with its roots in aircraft engineering – with the heater controls in the centre and seven gauges grouped into a pod and carefully arranged so that none is obscured by the wheel rim. The airy cabin has plenty of space up front and while rear passengers have a job to get aboard past the folder-forward front seats, once ensconced in the rear they find there’s plenty of room for them too.

Bristols were built to the highest standards but there is a potential for trouble – and especially for hidden hazards – in the chassis and body. The steel box-section chassis can rust in the sills, outriggers and suspension mounting points. The body panels are aluminium but mounted on a steel frame, and if water becomes trapped between the two, galvanic corrosion is likely. This wont be visible until the outer panels are removed, and restoration will be as eye-wateringly expensive as any other hand-built body, so when buying, inspection by an expert is essential to avoid any nasty surprises.

Interior work is also likely to be expensive because the materials are all top-notch, but virtually everything is handmade so at least individual parts can be removed and restored relatively simply. Make sure that the interior is complete – sourcing replacement parts is likely to be difficult and costly. The fuse box and battery are in the front-wing compartment on the right (driver’s) side, so if the water seal fails electric problems can result. Brakes and suspension rarely give trouble, but these are heavy cars so wear is inevitable. The Chrysler engines are long-lasting, good for 200,000 miles or more between rebuilds, and they are largely trouble-free if well maintained, as are the Torqueflite transmissions. Despite the rarity of these cars there is an enthusiastic club and there is plenty of support from the manufacturer itself for older cars. Running cars are rarely seen below £50,000 and concours examples sell for £100,000 or more. Even at that price, it’s a lot of class for the money.

Although the Honda NSX is a very different car, from a different era, it shares a good deal of the Bristol’s ethos. Like the older car it was designed to offer plenty of space, it is packed with quality engineering and its intelligent design makes it no more difficult to drive or own than a Civic. The aluminium alloy structure was a first on a volume-production car and its clothes in a dramatic, cab-forward shape with a long rear deck and huge wing which make a compelling statement of Honda’s intent. This was the Japanese company’s answer to exotica like the Ferrari 328 and Lamborghini Jalpa. Honda aimed to beat the Italians at their own game, offering all the thrills of the established junior super cars but with a painless ownership experience thrown in for good measure.

Hidden in the black pillar at the back of the door, just above the waistline, is a fingertip-operated latch for the wide, frameless door. It opens onto a black interior which has grippy-looking sports seats, but nothing much else of note. Its all nicely but together but the materials don’t look very special, and the steering wheel could have come from the Accord my dad ran in the Eighties. But the driving position is good and the view out is superb, framed at the front by the humps of the wings and with plenty of vision to the rear, which is unusual for a mid-engined car. The clutch is light and the alloy-knobbed gear lever slots easily into first. At sensible speeds the NSX turns out to be as easy to drive as that Accord. Yet there are signs that it has more to come. The 8000rpm redline on the tacho is one indication, the ominous burble from the non-standard straight-through exhaust on this car another. The steering is unassisted, and as the speed builds it faithfully transmits messages back from the front tyres. The NSX is easy to place on the road and it corners flat and fast; as the road opens out, the V6s mid-range snarl turns into an F1-style wail that builds and builds as the revs climb. The 3.0 litre V6 pulls strongly all the way, the torque curve bolstered by variable valve timing and lift electronic control (VTEC) and a variable income intake (VVIS) and not reaching peak torque until 6500rpm with peak power just 800rpm further on.

Its then that the NSX starts to make sense. Thoughts of the cabin being humdrum and the engine having two cylinders too few evaporate as I start to understand what an effective driving tool this is. Famously Ayrton Senna contributed to its development, and Honda also called upon the services of Japan’s first full-time F1 driver Satoru Nakajima and multiple IndyCar champion Bobby Rahal. It worked; The steering is precise and communicative, and the NSX feels compact and balanced. The engine is responsive and flexible without being so strong that it becomes an embarrassment, though the open exhaust on this car certainly attracts plenty of attention. The NXS is a modern classic that would work as everyday transport, but point it at these empty and enticingly twisty Yorkshire moors roads and it delivers driving thrills aplenty.

Suspension bushes and ball joints can suffer from hard use, and to replace the lower front ball joint you need an entire upright at a cost of in excess £1000. The engines can sometimes suffer from top-end oil leaks and should have the timing belt, camshaft pulley and water pump changed every seven years or 70,000 miles – a £2000 job. Check the coolant expansion tank and hoses for cracks and wear. Noise from the gearbox when in neutral with the clutch engaged can be a failing input shaft bearing. Early gearboxes can fail because of a broken countershaft bearing snap ring, but most will have been sorted out by now. A clutch change is an engine-out job costing £2000. Check for signs of accident repair and evidence that any work has been carried out by an expert, because refinishing the aluminium body has to be done properly to avoid further problems. Headlights are expensive on both the early cars with pop-up units and December 2001-on examples with fixed lights. High-mileage cars and the less-fancied autos and targas start around £30,000, with good manual cars around £50,000. NSXs from 1997 with the 3.2 litre engine and six-speed gearbox can go for £100,000 or more. The prices of all cars, particularly low-mileage manuals, have increased rapidly in recent years.

The Mazda MX-5 is a perennial bargain. It revitalised the market for affordable sports cars which had been in limbo for years following proposals to ban open roadsters from the US market. Thankfully that never happened, and the MX-5 arrived in 1989 after being conceived by Mazda’s Bob Hall in the US in the early Eighties, when rear-drive two-seat roadsters were thin on the ground. Design teams in Tokyo and Irvine California, produced competing concepts with the American design making it to production. Inspired by the Lotus Elan it was in truth quite a different kind of car – bigger and heavier, much more robustly constructed, safer and easier to live with. But it was also great fun to drive, and so it remains 30 years on.

Settling into David Gange’s 1991 car, I notice that the shapely seats have been retrimmed in leather, which some dealers did in period in response to customer demand to add a touch of class to the cabin. It looks good, thought I think there’s something to be said for the warmth of the original cloth. But the cockpit remains a snug place with just enough space for two, and its all the better for being beautifully simple. Clear white on black instruments sit in a binnacle on top of the facia behind a leather trimmed Momo three-spoke steering wheel. Little force is required at the wheel rim and that’s matched by the rest of the controls, making the MX-5 as easy to drive as an Japanese super-mini. Power-assisted steering was common, but not universal on the MX-5 MK1, and it helps when parking while doing little to hinder the flow of feedback on the move. The helm is precise and direct, and I can flick the little Mazda into bends with little effort. Tiny tyres – 185/60 x 14s on 5.5 rims – mean grip levels are never very high, so the Mx-5 can be steered on the throttle where the situation allows. Weight distribution is virtually 50:50 with driver aboard, contributing to the innate balance that makes the Mazda such a joy to drive. It doesn’t have the scalpel-like sharpness to its handling that characterises an Elan or a Toyota MR2, say, but it has a poise that makes tackling a switchback both simple and rewarding.

Extracting the most from the engine takes a bit more work, using the five-speed gearbox with its light, short-throw lever to keep it spinning hard. With 1114bhp propelling just over a tonne, the MX-5 is never going to be lightening quick in a straight line – but its fast enough to be fun. More power was available through Brodie Brittain Racing, which offered a turbo kit, and from 1994 the MX-5 gained a more powerful (128bhp) 1.8 litre engine, a longer final drive, bigger front discs and additional body stiffening, but some enthusiasts prefer the earlier cars. Many ex-Japanese market Eunos Roadsters have been imported – they are virtually identical to MX-5s, but often have air con and a metric odometer. Automatic transmission was a rare option in Japan and the US but not available in the UK.

The engines are reliable and will usually last beyond 100,000 miles if well maintained, though the earliest cars are known for crankshaft wear. Minor oil leaks from the cam cover are common. Clutches last well unless abused and gear changing problems are usually down to a failing slave cylinder which is easily fixed. Springs can corrode and crack, but generally the light overall weight of the MX-5 gives the running gear little trouble. Only the last MK1 cars were offered with ABS. Windows can stick in the runners, but cleaning and lubrication are all the remedy that is required. The convertible roof lasts well, though seals can deteriorate over time and the windscreen header rail clips can wear. Its important to raise and lower the roof when checking a potential purchase to ensure all the parts are present and work correctly. Rust can attack the wheel arches, sills, floors and A-pillar bases. Its important to ensure drain holes in the body and doors are kept clear to avoid rot.

Project cars can be had for £1000 and even the best MK1 MX-5s rarely sell for much beyond £5000, so they’re still very affordable. Though 400,000 of the first generation were built before it was replaced by the MKII in 1998, completely standard cares are becoming scarce. Owner David Gange says the lively MK-5 community is one of the highlights of owning the car, with a thriving owner’s club and Facebook groups like the ‘Bunch of Fives’.

Our last car, the Volvo 1225 Amazon, might look the most staid of the bunch, but it offers wonderfully evocative styling by Volvo’s long-serving chief designer Jan Wilsgaard. A step on from the upright PV series, it took its inspiration from the American cars of the early Fifties. Inside there’s more American influence, with chrome details on the facia and a fantastic strip speedo with a bright red ‘worm’ that grows from left to right to indicate speed. The gear lever is a long, chrome wand which disappears into the floor near the bulkhead, so gear changes are best made in a deliberate, unhurried fashion.

Despite that, the Amazon has a fair turn of speed for a saloon car of its day. Its not as heavy as you might imagine – of these six cars, only the little Mazda is lighter – so it gathers speed at a reasonable rate, with a willing thrum emanating from the four-pot motor under the bonnet. Acceleration is aided by short gearing, which results in fussy cruising. Owner Malcolm Crosher, like many other Amazon drivers, has swapped in an overdue gearbox, to reduce engine revs on motorway trips. He’s also added electric power steering which kicks in at a low speed to reduce parking effort, making it easy to take advantage of the Amazon’s excellent steering lock.

Most cars of the period made do with drum foot brakes, but the Amazon has discs, and where rivals had live axles and leaf springs for their rear suspension, the Volvo has a much more modern arrangement of coil springs, radium arms and a transverse Panhard rod to give very positive location. As a result it tackles these twisty Yorkshire lanes with aplomb, always feeling like its in control and never worried too much by the odd bump or pothole in the middle of a bend. It’s easy to see why these cars earned a reputation as good rally cars, in an era when soliduty, stability and crew comfort were more important than outright speed.

Amazons resist rust better than many contemporaries. Bonnet and boot lids are rarely affected and rotting outer front wings or front panel can easily be replaced. At the front rust can attack the inner front wings, battery box, radiator crossmember and engine cradle. The front chassis rails are susceptible, as are the sills and crossmember between the two. The main chassis rail from the front bulkhead backwards can be subject to significant corrosion, as can the rear end of the chassis, rear wheel arches, spare wheel well and boot floor. Doors rust at the bottom but repair panels can be welded in. On estates, the tailgate can rust, with no repair panels available, and rust can also affect the bottom edge of the rear side window. Brightwork is no longer available for early cars. Bumpers can be expensive so re plating the originals can be a good option. Interiors last well, but trim can be hard to source second hand. Watch for problems with the window winders caused by corrosion or breakage. Engines are good for 150,000 miles or more but work camshafts can cause tapping noises and valve guide wear leads to oil consumption and smoke. Spares for the early B16 engine can be hard to find but later B18 and B20 engines are better served. Gearboxes rarely give trouble. Cars in good condition start around £2500 and the best can reach £5000 or more. The rare 123GT, with the two-door body and 1800S-spec twin-carb engine, is the most sought-after and most valuable – but fairly easy to fake, so beware.

Picking a winner is difficult because these are such different cars with a wide range of values. The Volvo and Mazda are terrific fun, in very different ways, and wont cost the earth. The Bristol has effortless class, the Honda and Mercedes feel special yet are practical enough to use most of the year. If I were going to take one home it would have to be the Porsche: it has faults and idiosyncrasies, but no much character. Whichever you choose it’ll be anything but dull.

More from Journal

CARE

THE ULTIMATE CERTIFIED SERVICING INVESTMENT PLAN

Your ownership journey matters to us, which is why we have created a simple certified servicing investment plan, tailored to your individual needs and aspirations.

Start investing today and our dedicated CARE team will work with you to increase the value and enjoyment you receive from your vehicle.

STAY IN TUNE WITH SLSHOP MOMENTS

As part of SLSHOP’s community of enthusiasts, you’ll be the first to hear about events and tours, key product offers, exciting stories from owners around the world and of course… our latest additions to the showroom. So, be the first to know and you might just sneak a car on your driveway or take your car’s condition to new heights with our exclusive replacement parts.

Or, visit SLSHOP Journal